KUALA LUMPUR, March 26 — Parents have been told that they can apply for citizenship for their stateless Malaysia-born children using a special pathway under Article 15A of the Federal Constitution, but how does this play out in the real world?

Here’s a quick reality check, based on what lawyers told Malay Mail:

But first up, what is Article 15A and why is this important?

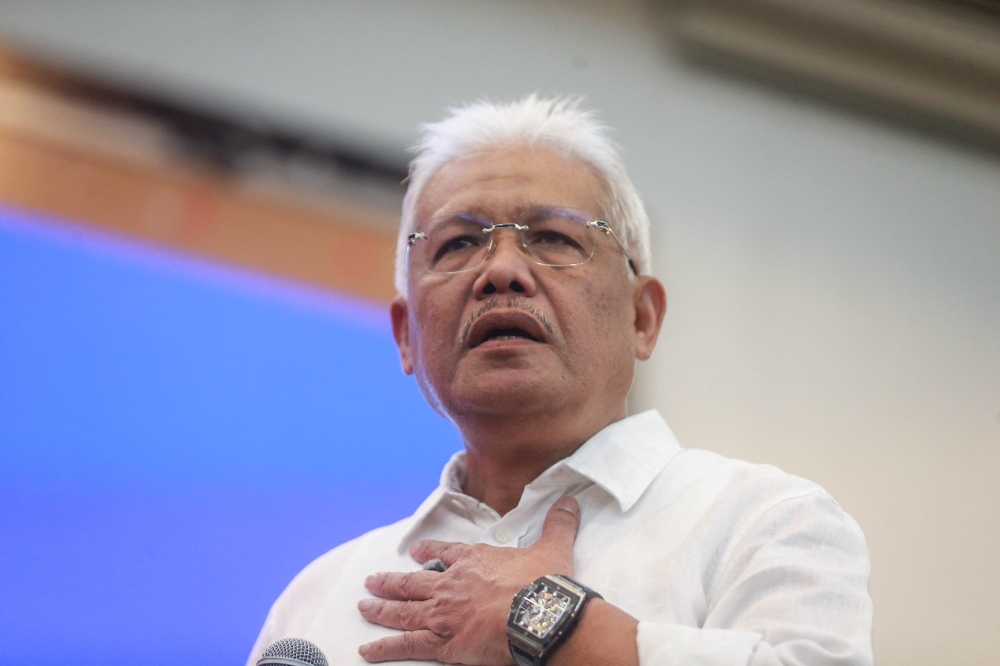

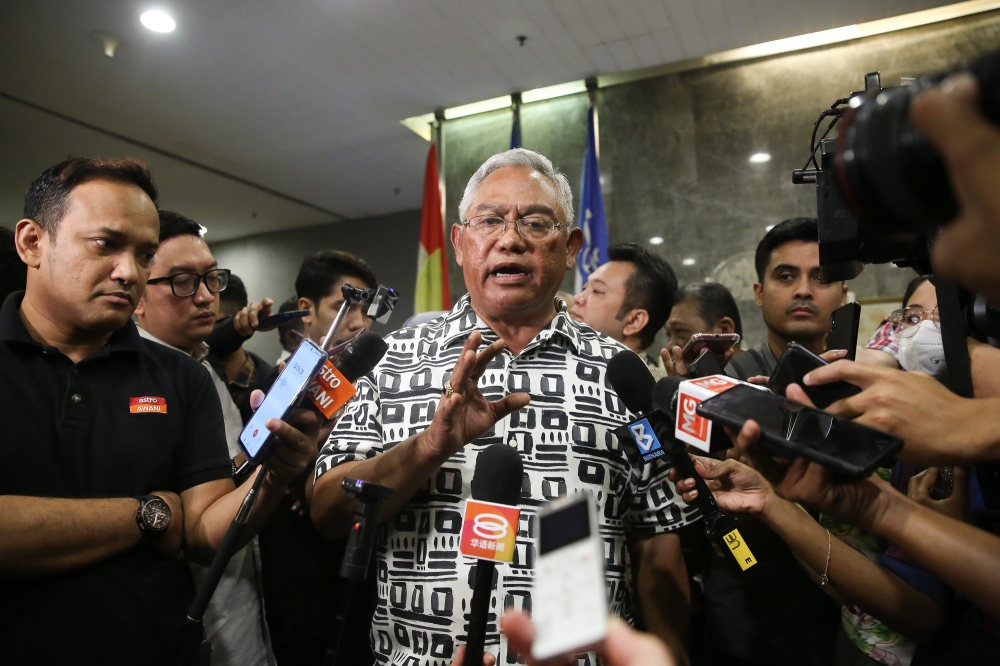

Deputy Home Minister Datuk Mohd Azis Jamman had in Parliament yesterday said children born to a Malaysian father and foreigner mother before their marriage is registered, are not Malaysian citizens, but they can apply to the National Registration Department (NRD) for citizenship under Article 15A and that such applications would be “considered” if constitutional and legal requirements are met.

Article 15A provides for the federal government’s special powers, where it can register anyone below the age of 21 as citizen in “special circumstances as it thinks fit”.

Azis also said: “It is the full responsibility of parents or guardians to handle the personal identification document and travel document with the country of origin of children who have the status of non-citizens before they become 21 years old, to avoid issues of invalidly being in this country.”

But it is not as simple as it sounds. And it really is not because the parents have not put in any effort.

The clock is running

The important thing about Article 15A is that it has a deadline of age 21 for anyone seeking to be recognised as a Malaysian.

For this citizenship pathway, that is a race against time.

Lawyers told Malay Mail of how their clients have to face the uncertainty in the wait that can drag on for years. And it often ends up in failure without them knowing why or what they could rectify or do to succeed in the next round.

Lawyer Larissa Ann Louis said her clients usually had to wait a minimum of one year for the government to reply to their Article 15A applications.

“They make it sound like you will get an answer immediately or even after a month or two or six, but the reality of the situation is there is a gap of close to even three years before they get a decision, which will most of the time be a rejection.

“By that time, they are close to 21 probably. So the parents are stuck with a decision if they should re-apply or wait or go to court,” she said.

What makes matters worse is that some parents have a late start in making such citizenship applications, with some doing so after realising the problem when applying for the identification card MyKad issued to Malaysians at age 12 or when enrolling their children in primary schools.

The rejection letters always have either “TIDAK BERJAYA” (unsuccessful) or “DITOLAK” (rejected) stated in bold, with no reasons given, Larissa said.

In a rare example, the first rejection for a client born to a Malaysian father and Filipino mother had carried the reason of unregistered marriage, but his second application was rejected with no reason given. He later obtained his citizenship after going through a legal battle.

In another case also involving a child born (in Perak in 2006) to a Malaysian father and Filipino mother, the first application in 2008 received no response, while the second application in 2011 was rejected in 2012, and the third application in 2013 rejected in 2016.

Maalini Ramalo, senior manager of non-governmental organisation Development for Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) Malaysia, said the average time for the government to reply on Article 15A citizenship applications is between two and three years.

“However, in recent times we have seen applications can stretch to more than four years awaiting response from KDN (Home Ministry).

“In thousands of cases DHRRA has assisted to date, among many Articles available for citizenship application, Article 15A has one of the lowest success rates along with Article 19 (naturalization). Further, cases are never given reasoning for the rejections,” she said.

Approval process opaque, subjective

Lawyer Raymond Mah said it is very difficult to succeed in an Article 15A application as most are rejected with no reasons given, noting: “There are no set guidelines for the approval of Article 15A applications, and the approval process is completely opaque and subjective.”

“Applicants tell us that they have to wait for two to three years (or even up to five years) to get a response to an Article 15A application. The response is typically in the form of rejection without reason. When applicants inquire as to the reason for the rejection, no reasons are supplied and they are simply invited to apply again and again,” he said.

Lawyer Simon Siah said no timeframe is given for the government to reply to Article 15A citizenship applications and applicants who call to follow up will be told to just wait.

“Article 15A is the final resort administratively. There is no other provision more powerful than this because this is the only provision for minors to obtain their citizenship based on the discretion of the minister.

“This Article 15A can even apply for children who are born of any circumstances such as if the identity of the parents is unknown,” he said.

“The minister does not even have to give the reason for rejection because the citizenship under Article 15A is his discretion alone.”

Maalini said Article 15A is not an easy route to citizenship, as it depends solely on the home minister’s discretion with no clear basis of under what “special circumstance” the approval is given.

“However, it can be a practical solution if the government has genuine intention to protect children whose parents (where) one is at least a Malaysian citizen. It is a matter of political will,” she said.

For those who failed in their Article 15A applications, Maalini noted that some choose to launch lawsuits.

“A few had opted to file cases at court but the process is lengthy and costly, with no successful precedents set at the Federal Court to date as parties opted to settle out of court,” she said.

Malaysia’s highest court almost had its chance recently to finally clarify important questions on citizenship for stateless persons, but the Home Ministry and the government granted citizenship to five applicants who filed lawsuits to be recognised as citizens just before the cases could be heard.

* Watch out for Part II of this report to be published tomorrow, where lawyers share what the alternatives are to Article 15A citizenship applications and possible reforms to help solve the problem of Malaysia-born children who are stateless because their parents were not yet legally married.

* Watch out for Part II of this report to be published tomorrow, where lawyers share what the alternatives are to Article 15A citizenship applications and possible reforms to help solve the problem of Malaysia-born children who are stateless because their parents were not yet legally married.