PUTRAJAYA, Feb 14 — The granting of citizenship today to three Malaysia-born boys after their long wait is a happy outcome but also represents a lost chance for the Federal Court to provide a permanent solution for other stateless persons, lawyers have said.

The three boys’ citizenship bid were initially scheduled to be heard today by the Federal Court after multiple delays, but the home ministry had yesterday evening abruptly informed that the trio would be granted citizenship instead.

This morning, the boys’ parents were given letters from the home ministry to inform them of the decision via Article 15A of the Federal Constitution, which provides for citizenship registration under special circumstances.

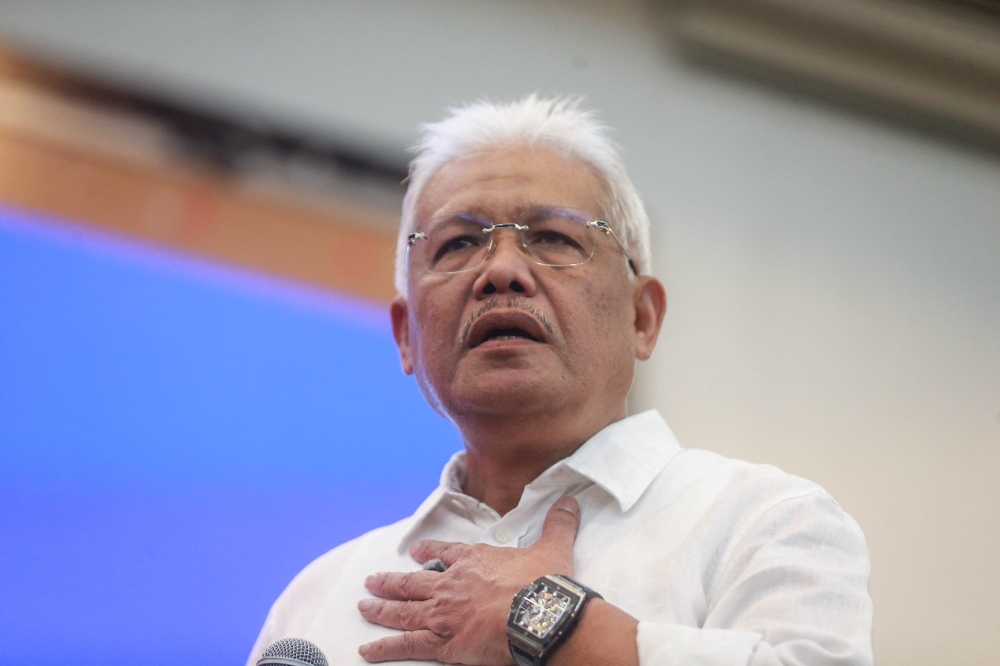

Lawyer Latheefa Koya, who represented one of the boys, told reporters that the government’s move was a “missed opportunity” for the Federal Court to hear and decide on key constitutional provisions that would affect the fate of other stateless persons.

“What we were seeking for is a ruling that these children are as of right Malaysian citizens, because they are not citizens of any other country and they are born in this country,” she told reporters, referring to Section 1(e) of Part II of the Second Schedule in the Federal Constitution.

When read together with Article 14(1)(b) of the Federal Constitution, Section 1(e) provides for anyone born in Malaysia but who are not born a citizen of any other country to be considered a Malaysian citizen by operation of law.

Latheefa cited a previous Court of Appeal decision when giving examples of the difficulties faced by Malaysia-born stateless persons seeking to rely on Section 1(e) to be automatically considered Malaysian citizens.

She gave examples of when children who were abandoned at birth were required to find their biological parents to ensure the latter were not foreigners, or to prove they are not citizens elsewhere.

“The continuous insistence of the Home Ministry and National Registration Department to ask for documents which are impossible to get is a punishment to these children,” she said.

Latheefa confirmed that there are no Federal Court decisions yet on the interpretation of these constitutional provisions, including Section 1(e).

“But the issue is still not resolved, we are still back to square one, because this is just the case for our client.

“The government is still responsible for the hundreds and thousands of kids who are still undocumented,” she said, later noting that she has about 50 pending cases involving other Malaysia-born stateless individuals seeking Malaysian citizenship.

She pointed out that Article 15A could be used by the home minister to grant citizenship for other stateless persons cases in Malaysia, just like for the three boys today.

“Article 15A is still a discretion of the minister, which we think the minister should be using it to resolve all the other pending cases,” she said, later adding the solution was as simple as by a “stroke of pen”.

Article 15A provides for the “special powers” of the federal government to register anyone aged below 21 years’ old as a citizen in “such special circumstances as it thinks fit”.

.jpg)

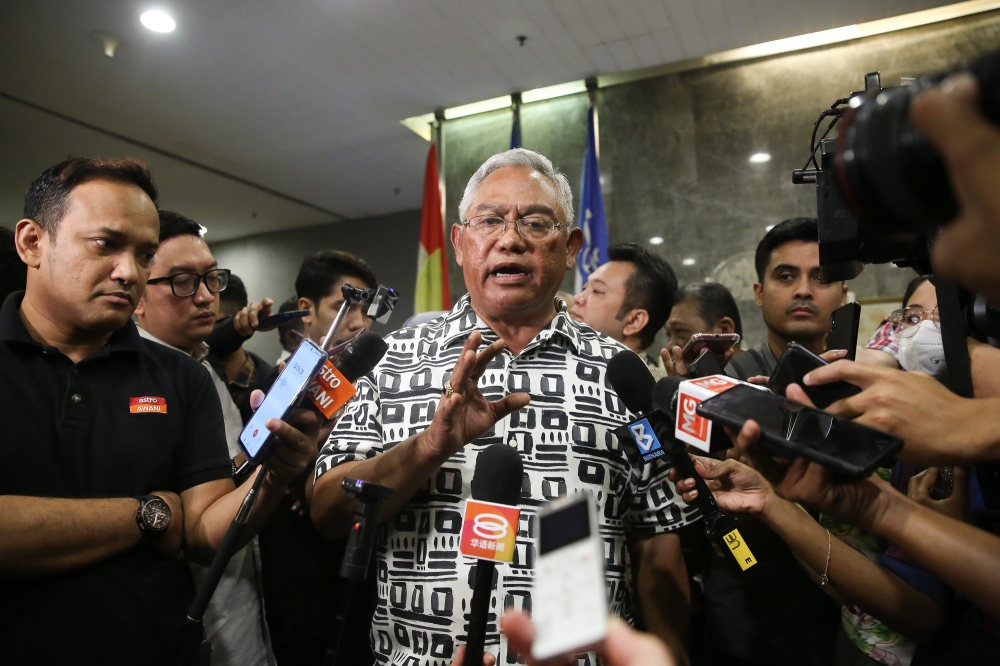

Lawyer Raymond Mah, who represented two of the boys whose biological parents are both unknown and were both legally adopted by two separate Malaysian couples, said a favourable decision for his clients if the Federal Court had heard their cases would have “created a binding precedent that would entitle other adopted children in the same situation to citizenship by operation of law under Section 1(a) and 1(e) of the Second Schedule”.

“That would have been better because it would apply across the board to all children in all future matters.

“Whereas the approval under Article 15A is on a case by case basis,” he told Malay Mail when met outside court.

Mah explained that citizenship by operation of law would mean being entitled to citizenship as of right, without having to apply under Article 15A for citizenship.

Without a Federal Court decision on the constitutional provisions, other stateless individuals who are born in Malaysia will for now either have to go through a costly and lengthy court process or apply for citizenship through the uncertain route under Article 15A that only applies if the individual has not turned 21.

Mah said the granting of citizenships under Article 15A is arbitrary and at the discretion of the minister.

Mah noted rejections of Article 15A applications by the home minister are not appealable, adding that the home ministry would usually advise for the application to be resubmitted for the minister’s further consideration if it has been rejected.

Mah is currently handling about two dozen other stateless person cases, with some of his clients’ cases previously put on hold at the High Court while awaiting the Federal Court’s decision in today’s cases.

Lawyer Datuk Cyrus Das similarly said that the issues that have yet to be decided will have to be raised in the future via other court cases.

“The problem is not solved yet, because this is all under Article 15A. Our claim was for citizenship by operation of law under 1(a) and 1(e) — that would have to come up in due course in other cases,” he said.

Section 1(a) provides for everyone who are born in Malaysia and who has at least one Malaysian parent at the time of birth to be recognised as a Malaysian citizen.

The two boys represented by Mah and Cyrus had initially wanted the Federal Court to decide on seven legal questions, including whether “parents” in Section 1(a) refers to a child’s “lawful parents” instead of biological parents.

The other questions include whether the post-adoption birth certificate — which typically names the adoptive parents as the child’s parents — will be conclusive evidence of the parents’ identity when deciding the child’s right to citizenship under Section 1(a).

Citing Section 2(3) of the Second Schedule’s Part II, the lawyers had also wanted the Federal Court to decide if a Malaysia-born child who did not become a citizen of any other country within one year of their birth date would become a Malaysian under Section 1(e); and whether the child had to prove both the parents’ identity and that they are Malaysians or whether it was enough for the child to show that he or she did not become a citizen of any other country within one year of their birth.

.jpg)