KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 28 — Another day, another Sichuanese restaurant opens in KL. Well, technically, MinJian Granary hails from Chongqing, which has been administratively separate from Sichuan since 1997.

But it was historically part of Sichuan and still is, at least in culinary terms: Chongqing is the birthplace of some of the most iconic Sichuan dishes, including suan cai yu (fish with pickled mustard greens), la zi ji (spicy dry chilli chicken) and, of course, the most famous of them all, the global phenomenon that is mala hotpot.

The restaurant group got its start in 2018 and now has multiple locations across China, including Chengdu, Lanzhou, Wuhan, Shanghai, Jinan and Beijing.

Our own branch, about a month old, occupies one of the bungalows along Lorong Yap Kwan Seng.

Its name means “folk granary”, or loosely, “granary of the people”, a nod to the warm, rustic ideal of the Chinese countryside.

To this end, the restaurant is designed to look like a large grain storehouse, only instead of sacks of grain, it’s stocked with one too many electric screens screaming the brand’s story at you, plus the occasional celebrity picture. Nicholas Tse and Charlene Choi both feature.

The property purportedly spans some 1,500 square metres, with dedicated parking around the back.

The main dining area is wide and expansive, while private rooms that require a minimum spend of RM800 line the right side. Calling ahead to book one of these is ideal if coming with a large group, as I did.

The menu is extensive, ranging from a few signature creations to mainly Sichuan and some Hunan classics, with even a handful of Cantonese dishes for those who can’t handle the heat.

But the latter bit does beg the question: why come to a Sichuanese restaurant at all? After all, heat and spice, along with generous amounts of boldly flavoured oil, are the very building blocks of Sichuan cuisine.

That combination of heat, spice and pungent oil is apparent even as we start with a cold dish: the classic Sichuan mouthwatering chicken (RM38).

The best thing about serving it cold is that the lower temperature lets the palate register every layer of flavour, from the tingle of Sichuan peppercorns to the tang of vinegar, the sweet nuttiness of sesame seeds and the spice and savouriness of chilli oil, all coming together for a truly drool-worthy experience (the Chinese name kou shui ji literally means “saliva chicken”).

Despite its lack of fiery oil and raging chilli, the crispy red kidney beans (RM28) are a standout.

Each bean is coated in a light dusting of flour and fried till crisp, while the inside puffs into a starchy, almost French-fry sort of texture.

The delightful little bites are flavoured with dried chillies, lots of garlic and chopped suan cai, the pickled mustard greens that feature so heavily in Sichuan food.

Another dish that lacks that stereotypically hostile level of spice is the shredded pork in fish-flavoured sauce (RM36). Fish-flavoured, or yu xiang, sometimes translated as fish-fragrant, is a seasoning mixture that’s essential to Sichuan cuisine.

Despite the name, there is no fish or seafood; instead, it is made from Sichuan pickled chillies, fermented bean paste, sugar and vinegar, which give it its characteristic sour, sweet and slightly hot profile. The mixture is cooked into a thick slurry with thin strips of velvety pork.

More than happy to play the stereotype, however, are the centrepiece dishes, two of Chongqing’s most famous exports aside from hotpot: la zi ji and mao xue wang.

The former is instantly recognisable by the laughably disproportionate ratio of dried chillies to chicken cubes, listed on the menu here as Chongqing spicy chicken (RM68).

Hidden among the literal minefield of dried chillies and Sichuan peppercorns are diminutive cubes of crispy, slightly salty chicken, if you can find them.

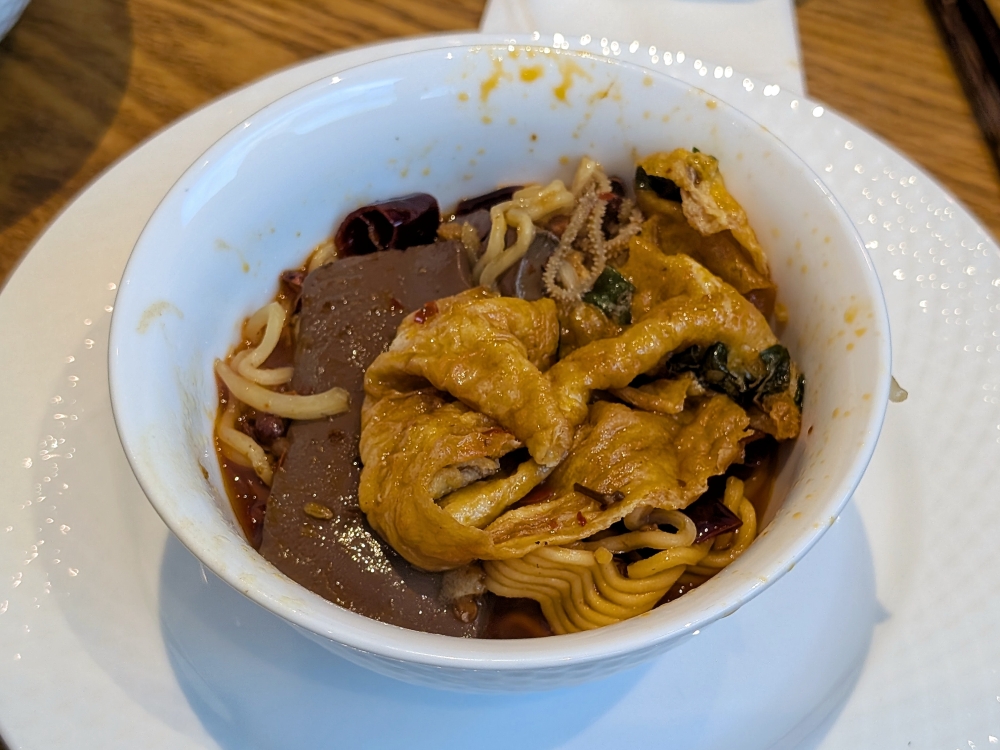

Sifting through it can get tiring after a while, but luckily, that’s not the case with the mao xue wang (RM88).

This traditional dish begins with a pot of furiously red oil, a shade so striking it invokes a gulp of primordial fear. The pot of death by a thousand chillies is brought to a boil, during which I clench involuntarily.

Next, the server brings a platter of various ingredients: prawns, squid, slices of pork, bean sprouts, luncheon meat, noodles, thinly sliced tripe and the titular ingredient, blood.

Typically, the dish calls for either duck or pig’s blood; from the slippery, silky texture here, I believe it is the former. For an additional RM12, an abnormally large fried omelette can be added to the mix, simply another vessel to soak up that terrifying broth.

I can only describe the process of waiting for everything to cook and assembling a bowl for myself as deeply disconcerting, spent fearing the worst with images of sweat and tears and all sorts of embarrassing waterworks flashing through my mind.

And yet, once it cools from piping hot to a realistically edible temperature, I found myself cleaning up every last drop in my bowl, without a bead of sweat in sight.

Yes, you can choose your level of spice, and I suspect they defaulted to mild for our table, but too often mild has meant no other flavours either.

That’s not the case here. It’s remarkably well-balanced, shockingly so, with just the right amount of savouriness to keep the tongue interested without being eviscerated by spice.

It was RM12 well spent, especially for the oily fried egg, which is the best bit after being soaked through with even more oil and broth. This is heavy food, not for the faint of heart, and I loved it.

The only thing to look out for is that once you eat this, your palate ends up overstimulated, and only similarly strong or heavy dishes will stand out after.

Luckily, the menu has no shortage of such dishes. Two of the best include the braised chicken with potatoes (RM68), bursting with the flavour of tomatoes and lemongrass and perfect over rice, and the sweet, sticky Cantonese braised pork belly (RM48), though I feel it is somewhat lost in translation.

It’s listed as hong shao rou in Chinese, which is a Hunan dish, and which the dish’s glossy, luscious glaze more closely resembles anyway.

Now, for the two gimmicky items of the night. The first is a giant “kung fu” sesame glutinous rice ball (RM38), which is exactly that and nothing more. Just crispy bits of sweet, nutty glutinous rice and sesame forming a completely hollow ball that’s frankly just for show.

But it’s not all bad, far from it in fact, because when dipped into the mao xue wang or used to scoop up the braised chicken with potato mixture, it becomes absolutely delicious.

The second, a creative take on yu xiang eggplant (RM36), deep-fried in a roll and served with the sauce on a sizzling plate, was unfortunately much worse.

The sauce did not come through with that sharp, robust flavour, the eggplant inside the batter was bland, and worse still, the batter was chewy rather than crunchy, like a pisang goreng left out for too long.

It was a real disappointment to end on, which was unfortunate considering how good everything else had been. Moral of the story? Avoid this, but everything else is definitely worth a try.

MinJian Granary 民间粮仓

67, Lorong Yap Kwan Seng, Kuala Lumpur,

Open daily, 11am-10pm.

Tel: 017-376 4861

Instagram: @minjiangranary

* This is an independent review where the writer paid for the meal.

* Follow us on Instagram @eatdrinkmm for more food gems.

* Follow Ethan Lau on Instagram @eatenlau for more musings on food and occasionally self deprecating humour.