DECEMBER 11 — China’s recent claim that it seeks a “fair and just maritime order” in the South China Sea comes at a delicate moment for Southeast Asia.

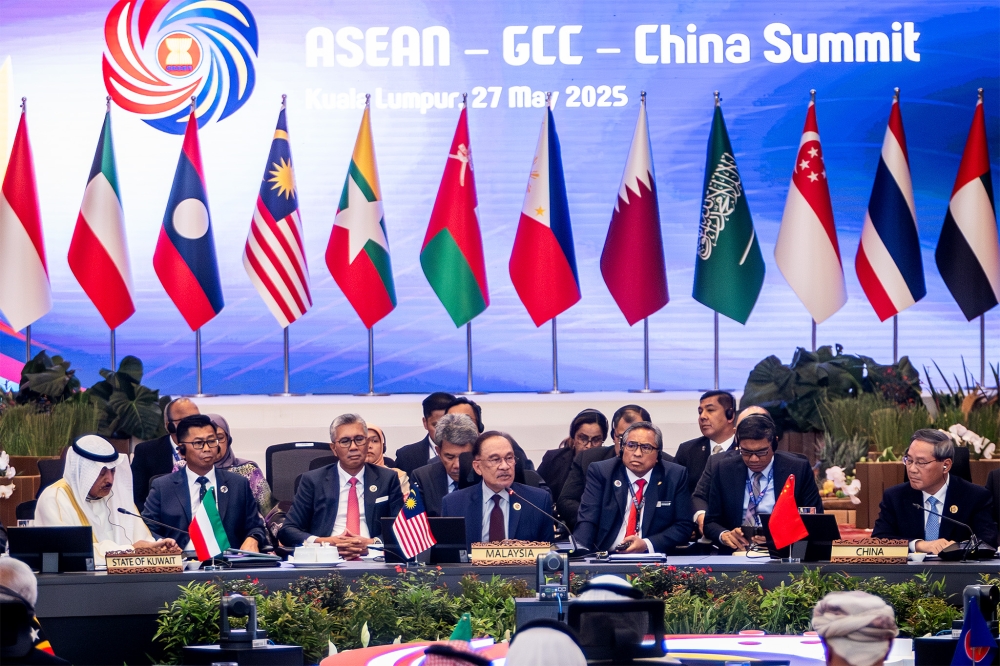

Malaysia is nearing the end of its role as Group Chair of Asean and Related Summits, a period defined by overlapping crises and shifting power realities.

This statement by Vice Foreign Minister Sun Wei Dong from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing is not a routine diplomatic gesture.

It is a strategic affirmation of the kind of maritime order China wants Asean to gradually accept.

By again rejecting the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling as violating “fundamentals of international law,” China signals that its version of fairness relies on historical narratives rather than legal adjudication.

Malaysia’s chairmanship has unfolded within this complex environment.

The Thai–Cambodian border relapse, worsening Philippine–Chinese encounters at sea, and Myanmar’s civil conflict have all demanded diplomatic steadiness.

These tensions form the real context behind China’s latest statement.

Southeast Asia today operates within a uni-multipolar world.

The United States remains the global military anchor.

China is a system-shaping power with the capacity to redefine norms.

Asean sits between both, each member compelled to navigate vulnerabilities similar to those faced during past geopolitical transitions.

In such a world, China’s reference to fairness serves multiple purposes.

It is a response to the rising tempo of US naval operations in the South China Sea.

It reminds Asean that China views its maritime actions as restorative, not expansionist.

And it signals China’s domestic audience that sovereignty remains non-negotiable.

The timing is important.

Asean is internally divided, with several member states absorbed by domestic political transitions analogous to earlier periods of regional distraction.

Fragmentation weakens Asean’s collective leverage.

China understands that bilateral diplomacy gives Beijing a stronger hand than dealing with Asean as a unified bloc.

Malaysia’s chairmanship has attempted to maintain coherence despite these pressures.

Kuala Lumpur has emphasised diplomacy, verification mechanisms, and confidence-building — tools essential for preventing flashpoints from escalating.

This steadiness has kept Asean focused on long-term priorities, even as tensions intensified on multiple fronts.

China’s message also anticipates the Philippine chairmanship in 2026.

Manila has become increasingly assertive in confronting China’s maritime activities.

Beijing recognises that the Philippines will likely push for stronger language and firmer commitments on the Code of Conduct (CoC).

The CoC remains the region’s most important diplomatic mechanism for managing maritime disputes.

Yet negotiations remain stuck.

The key disagreements — whether the CoC should be binding, whether foreign navies should be excluded, and whether dispute settlement should be mandatory — reflect deep structural differences between China and Asean claimants.

Malaysia’s chairmanship has kept these negotiations moving, even if slowly.

By ensuring that regional tensions did not overwhelm diplomatic channels, Malaysia provided Asean the necessary space to sustain dialogue.

This continuity is crucial as leadership transitions to the Philippines.

Yet the fundamental challenge remains unchanged.

China’s concept of fairness diverges sharply from Asean’s.

For Beijing, fairness is derived from historical continuity and civilisational claims.

For Asean claimant states such as Malaysia, Vietnam, Brunei, and the Philippines, fairness comes from Unclos.

For non-claimant states, fairness equals stability and economic partnership with China, analogous to their existing patterns of engagement.

This differing understanding of fairness explains why Asean struggles to articulate a unified maritime position.

It also highlights why Malaysia’s leadership has been essential.

By keeping the focus on legal principles and diplomatic pragmatism, Malaysia has prevented Asean’s maritime posture from drifting toward ambiguity.

As Malaysia approaches the end of its chairmanship, three imperatives stand out.

The first is the legal imperative.

Unclos must remain the foundation of maritime entitlements.

If historical claims override legal norms, regional stability will erode.

Asean cannot accept an arrangement analogous to a dual-track maritime order where history and law compete for primacy.

The second is the strategic imperative.

Asean must strengthen maritime domain awareness and crisis-response protocols.

Regional incidents escalate quickly when verification is slow or absent, similar to recent confrontations that grew from misinterpretations.

The third is the diplomatic imperative.

China’s civilisational narrative must be acknowledged, but Asean cannot anchor its long-term security on historical interpretations.

Predictability requires rules, not rhetoric.

A maritime order built solely on unilateral narratives would be analogous to a system without brakes.

China’s declaration of wanting a “fair and just maritime order” should therefore be read with caution.

It is an attempt to shape Asean’s expectations ahead of a new chairmanship and negotiation cycle.

It signals reassurance, but also reassertion.

As Asean prepares for 2026 under Philippine leadership, clarity is essential.

Asean must ensure that the South China Sea does not become a theatre where conflicting definitions of fairness undermine regional unity.

The region has experienced analogous periods of tension before, but the stakes are higher now due to overlapping crises and great-power contestation.

Malaysia’s chairmanship has provided Asean with stability during a turbulent year.

It has kept the region focused on shared principles despite multiple crises.

The challenge now is for Asean to maintain this coherence as a more assertive claimant state takes over.

The South China Sea will remain the defining test of Asean’s unity and relevance.

Stability will depend not only on the actions of China and the United States, but on how Asean interprets and responds to competing visions of maritime order.

Malaysia has kept Asean steady in 2025.

The task ahead is ensuring that the region remains steady still — and that Asean’s understanding of the South China Sea grows sharper, not softer, in the years to come.

* Phar Kim Beng is a professor of Asean Studies and director at the Institute of International and Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.