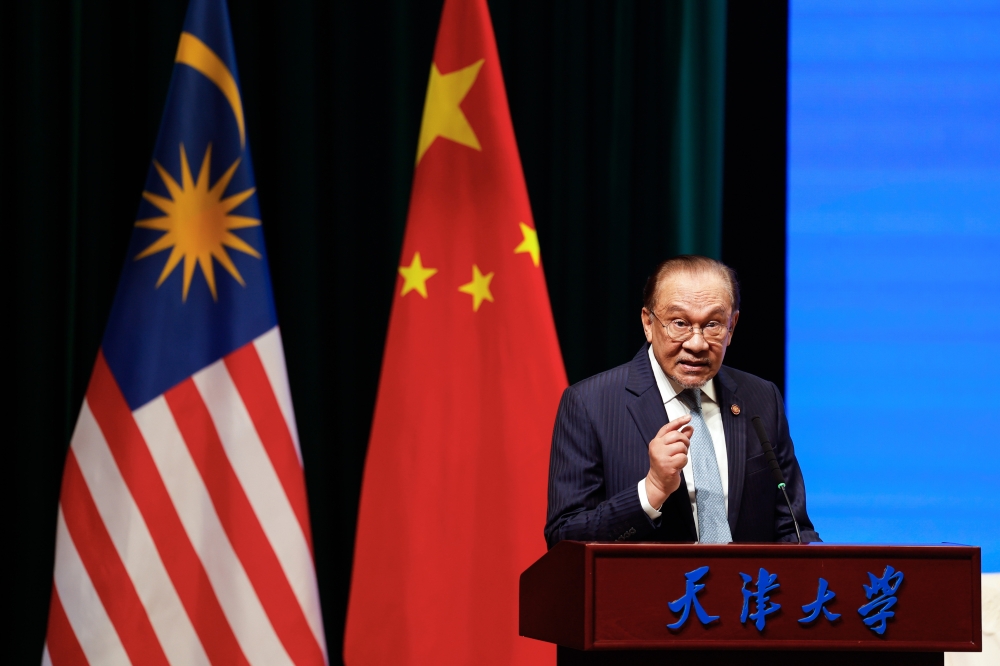

NOVEMBER 10 — Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s recent assertion that Malaysia’s close ties with both the United States and the People’s Republic of China are forged “with the nation’s interest in mind”.

This policy underscores his commitment to a foreign policy anchored in broadening and deepening Malaysia’s international relationships.

His position reflects the determination to engage with all strategic partners while safeguarding national sovereignty and independence.

Yet, in an era of intensifying Sino–US rivalry, public criticism of such a strategy is inevitable. The dyad between Washington and Beijing has grown so polarised that any attempt to deepen ties with both simultaneously invites suspicion at home and abroad. Malaysia’s decision to pursue economic complementarity with China and technological cooperation with the United States places it directly under the microscope of geopolitical scrutiny.

Strategic context

Anwar’s foreign policy vision represents a shift away from mere hedging toward a broader and deeper engagement with multiple centres of power. Malaysia is expanding its partnerships beyond the United States and China to include Japan, South Korea, India, the European Union, and the Gulf Cooperation Council. As Asean Chair in 2025, Kuala Lumpur’s leadership emphasizes inclusivity, cooperation, and balance across the Asia-Pacific and Indo-Pacific.

China remains Malaysia’s largest trading partner, accounting for over 17 per cent of total trade. The United States, meanwhile, remains indispensable for foreign direct investment and advanced technological cooperation in semiconductors, digital trade, and clean energy. Through Asean, Apec, and the G20, Malaysia seeks to translate these ties into sustained economic resilience and global influence.

Anwar’s insistence that he “does not mind criticism because my priority is Malaysia’s growth and standing” captures the reality that leadership in this polarized environment demands conviction and consistency, not mere diplomacy

Public criticism and polarised perceptions

The first source of criticism arises from the great-power lens itself. In a global order increasingly defined by zero-sum thinking, Malaysia’s engagement with both powers is rarely interpreted as pragmatic. Washington expects clearer alignment with its Indo-Pacific framework, while Beijing views Malaysia’s engagement with the US as a potential constraint on its own regional ambitions. Consequently, Malaysia’s balanced posture is often misunderstood as ambivalence or opportunism.

Domestically, the polarisation of perceptions is equally pronounced. Political parties and civil society groups interpret the government’s international engagements through their own ideological lenses. Cooperation with Washington is sometimes viewed as inviting external interference, while deals with China are framed as risks to sovereignty. These critiques reflect Malaysia’s broader struggle to define the boundaries of national interest in a multipolar world.

Transparency and trust form another crucial dimension. Deepening ties with the United States may bring opportunities for high-value technology transfers but can also expose Malaysia to strategic dependencies, especially in defence or cybersecurity.

Similarly, Chinese investments in infrastructure, ports, and industrial parks are vital for economic growth but can raise questions about long-term economic dependency. Balancing these sensitivities requires constant communication with the public.

Beyond the strategic and economic realms lies Malaysia’s identity as a civilisational bridge.

Rooted in Islamic and Asian values, Malaysia seeks to mediate rather than take sides. But the very act of balancing — between democracy and development, autonomy and cooperation — exposes the leadership to endless scrutiny.

Navigating the Dyad

The US–China dyad traps many nations in a binary framing — as if choosing one is rejecting the other.

Malaysia’s approach of broadening and deepening relations with both is an act of diplomatic defiance against that logic. Yet, it requires precision, patience, and persuasion.

The two powers’ agendas diverge sharply. The United States foregrounds alliances, human rights, and supply-chain resilience. China promotes infrastructure development, trade expansion, and non-interference. For Malaysia, this divergence means that every agreement carries asymmetrical expectations.

When Malaysia signs trade pacts with Washington, Beijing watches for strategic implications; when Malaysia welcomes Chinese industrial zones, Washington asks about compliance with global standards.

The domestic resonance of these choices is significant. Malaysia’s public remains sensitive to issues of sovereignty and economic independence.

Even benign cooperation can spark nationalist backlash if perceived as infringing on domestic control. As Asean chair, Malaysia’s balancing act also influences regional cohesion. A perceived tilt to either side risks unsettling the bloc’s unity, which Anwar has pledged to strengthen.

Building confidence through broadening and deepening

Malaysia’s foreign policy credibility depends not on avoiding criticism but on making its broadening and deepening strategy deliver tangible results. Every partnership must show value beyond summit communiqués.

This begins with articulating clear objectives. Agreements with both the United States and China should outline measurable outcomes — technology transfer, education exchanges, digital infrastructure, and renewable energy collaboration. Deliverables make diplomacy visible.

Institutional oversight is equally essential. Transparent mechanisms involving parliament, academia, and the private sector can ensure foreign cooperation serves long-term national priorities rather than transient political gain.

Diversification remains a cornerstone. Malaysia must show that it is not defined by the Sino–US rivalry alone. Strengthening ties with Japan, India, the GCC, and the EU reinforce Malaysia’s multi-vector diplomacy.

This approach transforms Malaysia from a reactive actor into a regional norm-setter capable of shaping multilateral outcomes.

Anwar’s broader narrative also rests on civilisational diplomacy. His articulation of Maqasid al-Shariah — the higher objectives of justice, balance, and compassion — provides an ethical compass for Malaysia’s foreign policy.

It allows Malaysia to pursue modern partnerships while grounding them in timeless moral values.

Conclusion

Anwar Ibrahim’s declaration that Malaysia’s ties with both the United States and China are “forged with the nation’s interest in mind” is more than a statement of neutrality — it is a declaration of agency.

Broadening and deepening Malaysia’s partnerships ensures the country does not become a pawn in a polarised order but a player with its own strategic vocabulary.

Still, in a world where the Sino–US dyad shapes global discourse, neutrality is no longer immune from attack. Anwar will continue to face criticism, not because he has failed to act, but because he has chosen to act differently — to assert Malaysia’s sovereignty through multiplicity rather than subservience.

Ultimately, Malaysia’s challenge is not to choose between the US and China, but to define itself amid them — to demonstrate that broadening and deepening relations with all powers is the surest path toward prosperity, dignity, and peace.

* Phar Kim Beng is Professor of Asean Studies and Director, Institute of International and Asean Studies (IINTAS) International Islamic University Malaysia

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.