APRIL 6 — Disbursements of the Prihatin package this month will bring welcome relief through emergency cash injections for B40 and M40 households and deferred loans, rent and other costs.

Malaysia’s Covid-19 response is helping protect jobs and incomes, but there is still much room for tripartite deliberations and compromises to achieve more adequate and fairly distributed relief, and conduct scenario planning for the months ahead.

The gravity of imminent crises calls for the formation of a tripartite taskforce on employment and income.

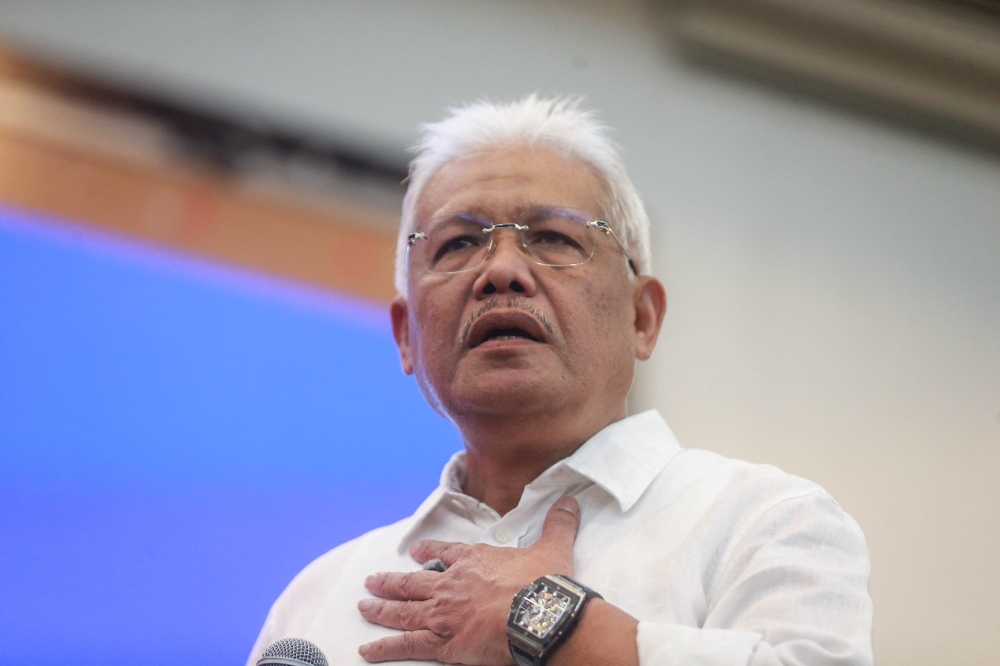

While MTUC and MEF, representing workers and employers, both commended Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin for extending the assistance, discontent has also heightened and major gaps have been highlighted.

SMEs voice dissatisfaction at the lack of support, especially the inadequacy of the wage subsidy. Many have noted the scarce attention to highly vulnerable low-income self-employed.

Workers are concerned at the limited legal force in the government’s directive to employers to keep paying full wages. The situation of migrant workers, particularly those at the mercy of labour contractors who operate with much less accountability, is troublingly unclear.

With the MCO precluding access to densely populated places, we have little information on conditions in their cramped living quarters where they are now presumably confined.

It looks like the government will introduce a relief package for SMEs. Perhaps it will facilitate more self-employed access to Employment Insurance Scheme (EIS). Such responses will be well-received, even if it has been a batch-by-batch release.

The piecemeal approach taken so far is perhaps unavoidable, and somewhat excusable, in the early stages of a colossal crisis under MCO which hinders intensive face-to-face meetings to coordinate multi-agency and tripartite efforts.

But by this point, shouldn’t MTUC’s public appeal for SME aid to safeguard workers’ welfare be presented at the planning table?

The spectre of a massive wave of unemployment is real and must be anticipated concertedly.

Current policies still apparently operate with an underlying assumption of best case scenarios:

SMEs have reserves, and the will, to ride out the shutdown, hence with a bit of help can subsequently get back on their feet.

The Employment Retention Programme (ERP) provides a flat RM600 subsidy per worker, amounting to 30 per cent for a RM2,000 salary and 15 per cent of RM4,000. This pales in comparison to many countries, such as the UK’s 80 per cent (to a maximum £2,500 or RM13,347).

Malaysia’s ERP is conditional on companies suffering 50 per cent or more loss of income since January; those with more recent downturns may not qualify.

New Zealand’s wage subsidy provides fixed rates for full-time and part-time workers, to companies losing 30 per cent income due to Covid-19 and with some flexibility for wage adjustments.

Some employers will become inclined to retrench some workers, weighing the costs of retrenchment settlements and rehiring later versus keeping all on board and taking the ERP.

Retrenched workers will have to subsist on retrenchment and EIS payments. Some SMEs might close shop altogether, or place workers on no pay leave for them to claim RM600 per month, and Bayaran Prihatin and Bantuan Sara Hidup for April-May.

Should the MCO be extended, firms’ reserves will be further depleted and pressures will mount. Even if the MCO becomes relaxed, so much remains unclear — which sectors will be allowed back to work, when, and how.

But one thing is certain: There is no simple getting “back to business.”

Tourists will not flood back in, consumers will not rush back to shops and malls, large swathes of manufacturing will face shrunken demand, a global recession all but inevitable.

Multitudes of migrant workers, at high risk of Covid-19 infection but anxious to come forward to health services, may go into hiding or be subjected to abuses, which potentially triggers diplomatic crises.

This is not the space for worst case scenario projections, not even for asserting policy actions.

Indeed, that would perpetuate piecemeal and uncoordinated measures, compounded by the limited information on hand.

It is time for the government to convene a tripartite taskforce to collate information, hammer out compromises and coordinate policy responses, with workers, employers and government at the table — physically or online.

This special taskforce can build on the existing National Labour Advisory Council, which has not been proactive and decisive. By default it falls under the Ministry of Human Resources’ purview, but it must also have representation of multiple ministries.

It should also include organisations with ground-level insight on the self-employed and migrant workers, labour data experts and legal advisers.

The adequacy of the current wage subsidy is an obvious issue of immediate importance, but also the feasibility of maintaining full wage payments. Thus far directives to employers leave the actual decisions to their discretion.

The tripartite system can more authoritatively provide guidelines, advisories and policy proposals, for the possible deepening of employment and income crises, when temporary wage adjustments — a taboo so far — cannot be discounted.

Malaysia needs clarity on how to uphold fairness, morale, solidarity and decency while safeguarding business survival, worker welfare and the national interest.

This current phase of essentials-only production also limits consumption; household expenses are reduced across the board. Lower-income households remain more dependent on wages and more likely to inject money back into the economy because they spend a larger proportion of their income.

If businesses become compelled to cut wages, all employees and business owners should bear a fair share of the sacrifice, on moral and economic grounds.

The MCO effectively prohibits face-to-face negotiations between employers and employees. Although they can also use mobile apps, it is highly unlikely that such meetings will take place, moreover when there may be no legal obligation for employers to consult.

There should be a moral obligation to act fairly — and a common understanding on how best to proceed.

Tripartite deliberations can distinctly contribute by establishing obligations and best practices. Employers should be required to make reasonable effort to consult workers — and guided on how they should go about this. Further guidance will also be needed on the conditions for which temporary wage adjustments can be pursued and legally sanctioned.

Such process should establish a wage floor (say, no one earning below RM2,000 should suffer a cut) and consider a proportionate basis first, with lower paid workers taking a smaller cut, for instance 20 per cent, while higher paid workers take 25 per cent.

If companies opt for an absolute amount, whether RM300 or RM600, a similar progressive approach must take precedence, corresponding with wage brackets.

Compromise on a national set of obligations and recommendations, formulated by the Ministry of Human Resources, MTUC and MEF, and other tripartite representatives, will provide some answers to the clarion call of unprecedented measures in these unprecedented times.

This tripartite taskforce should also deliberate on advisory interventions, for instance to urge workers to refrain from EPF account 2 withdrawals under i-Lestari, in view of forthcoming Prihatin payments.

Energy can also be channelled toward facilitating how staying-at-home workers can be productively engaged, such as through online skills training modules.

Millions of workers cannot be at work and face grave uncertainty; the tripartite system must work hard for them. While collective action is as difficult as can be, collective action is more necessary than ever.

* Lee Hwok Aun in a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.