FEBRUARY 4 — “Even the most ruthless satirists have their sacred cows.” What did the poet Saladin Ahmed mean by this in the context of Charlie Hebdo?

A month has passed since 12 of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists and staff were murdered because of their satirical take on Prophet Muhammad, but the debates still run strong.

What is satire? Its place in society? What are these sacred cows?

Satire makes people laugh while challenging them to see powerful individuals, institutions, governments or religions in a different light.

When at its best, it prompts constructive social criticism leading to reform and improvement—performing an invaluable public service as the argument goes. From the ancient Greek comedies of Aristophanes and Rome’s satirical poets Horace and Juvenal to modern day satire, it bubbles and blossoms — defying attempts to tame it — up from the roots of almost every society we see today. France boasts a long and deep affinity with satire; albeit one kept on a tight leash.

In the eyes of the law, satire is allowed to run riot. Belonging to the field of art or artistic expression, it enjoys not only the protection of freedom of speech, but that of culture and of scientific and artistic production.

A mightily privileged position you might say, but one that carries a duty: to dish out the satirical-dirt equally, sparing none from its stinging bite.

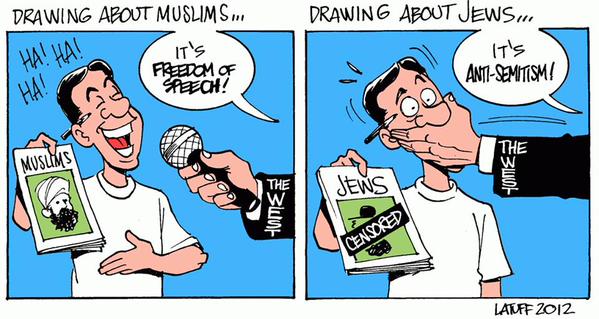

Charlie Hebdo says it satirises every religion, fervently challenging claims of racism. But, I think the American-Arab poet and novelist has a point: as ruthless as Charlie Hebdo is, they have their “sacred cows.”

Before I continue, I want to just say that nothing justifies the savage slaughter of these journalists. Guns cannot silence satire; they amplify it.

I had never heard of Charlie Hebdo before these attacks, but I’ve read and researched a lot about them since. In the process, I came across interesting information that points, at the very least, to double-standards at the magazine.

Olivier Cyran, who worked for Charlie Hebdo for nine years before resigning in 2001, wrote an open letter in December 2013 addressed to Stéphane Charbonnier (magazine’s director killed in January’s attack). He gives a detailed explanation supporting his claim of the magazine’s descent into racist, anti-Islamic rhetoric in the post 9/11 era.

It’s a powerful letter. Tinged by the bitterness of a disgruntled employee (he’s pretty acerbic), but his concern of self-censorship at Charlie Hebdo based on the satirists’ own filtered view of the world, is both palpable and sincere.

He describes “a distressing transformation” and an “Islamophobic neurosis” which took over the team after the 9/11 attacks in New York. And that their: “obsessive pounding on Muslims to which Charlie Hebdo devoted itself for more than a decade… has powerfully contributed to the idea that Islam is a ‘major problem’ in French society.”

There is also the cartoonist Maurice Sinet, sacked by Charlie Hebdo in 2008 for a writing an anti-Semitic piece about the son of the former French President Nicholas Sarkozy, suggesting that he might convert to Judaism for financial gain following his marriage to a Jewish heiress. Sinet later sued for wrongful termination and won damages.

Smacks of political correctness for Judaism, the “sacred cow”, but for Islam, anything goes?

Smacks of political correctness for Judaism, the “sacred cow”, but for Islam, anything goes?

While Charlie Hebdo was targeting Islam in general, it has an exclusively French readership (until recently). There are five million Muslims living in France — I wonder whether staff members considered the impact of its mockery on them?

The descendants of immigrants from France’s former colonies, representing the largest Muslim population in Europe, are also the most marginalized and impoverished sectors of French society. Locked out of power, ignored, rejected, experiencing acute levels of prejudice. Potent breeding grounds for radicalism?

Charlie Hebdo rightfully point out in their post-attack edition that the problem results from the French government’s failure to properly integrate and care for its Muslim communities.

Nothing to do with them; they only added insult to injury.

And why not? Others are! And doing a better job than Charlie Hebdo’s small fry weekly print run of 60,000.

France’s current bestselling books include: Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission (submission) and Éric Zemmour’s Le Suicide Français. The first envisages a France governed in 2022 by a radical Muslim president, where polygamy rules and women are boxed into their homes. The second encapsulates the same strong anti-immigrant ideas that the popular leader Marine Le Pen of the right-wing National Front party, espouses.

A telling insight into the national psyche?

Let me end with another of Saladin Ahmed’s insights:

“The belief that satire is a courageous art beholden to no one is intoxicating. But satire might be better served by an honest reckoning of whose voices we hear and don't hear, of who we mock and who we don't, and why.”

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.