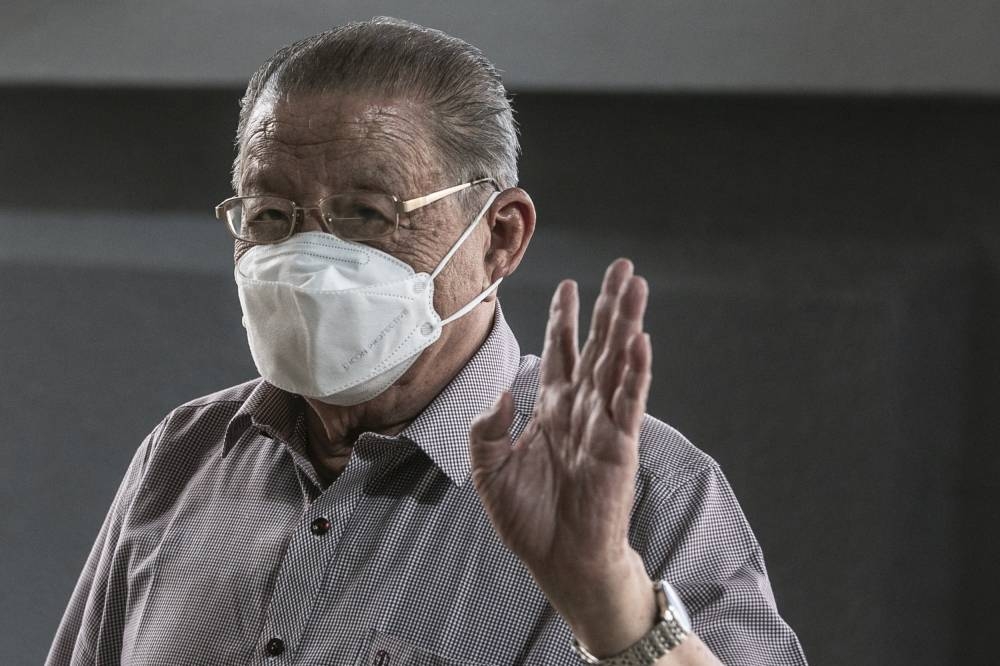

KUALA LUMPUR, July 23 — Former attorney general Tan Sri Mohamed Apandi Ali had in July 2019 sued DAP MP Lim Kit Siang for defamation for having publicly urged him to “explain why he aided and abetted in the 1MDB scandal”.

But the High Court on May 23 this year dismissed Apandi’s defamation lawsuit, after having found that the evidence produced in court — including Apandi’s own testimony — showed Lim as having successfully proven his defences.

On July 21, High Court judge Datuk Azimah Omar’s 100-page written judgment was made available publicly, where the judge gave a hard-hitting and took a no-nonsense approach in scrutinising all the evidence available, especially on why Apandi had not asked for continued investigations on 1MDB or SRC.

The judge stressed that Apandi’s defamation lawsuit is mainly related to the “globally infamous” 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal (which also includes the SRC International Sdn Bhd case), which she said is still plaguing Malaysia to this very day and also noted that history can only regard the scandal as the “greatest and vile corruption and thievery of the modern times”.

Here’s Malay Mail’s quick summary of the full written judgment:

1. What happened in this case?

On May 6, 2019, Lim had published an article titled “Dangerous Fallacy to think Malaysia’s on the road to integrity” on his own blog, which contained a line saying Apandi “should explain why” he had allegedly “aided and abetted in the 1MDB scandal”.

Apandi claimed that Lim’s remark was defamatory and had tarnished his reputation as Malaysia’s former attorney general, insisting that he had only cleared then prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak in 2016 based on available evidence then.

Lim argued that his comments were not defamatory, and that his statement regarding Apandi were either justified, fair comment, or a qualified privilege.

In defamation lawsuits, some of the defences that can be used are justification or being truthful, fair comment or qualified privilege.

To prove that a statement is defamatory, it has to be shown that the words are defamatory, the words refer to the person who is suing, and the words were published to third parties.

In this case, Lim had confirmed that the words were referring to Apandi and were published, with the High Court then focusing on the words “should explain why he aided and abetted in the 1MDB scandal” to determine whether they were defamatory.

The High Court said it would be far-fetched to assume that ordinary members of the public without special knowledge of criminal law would interpret “aiding and abetting” as a criminal offence under Malaysia’s laws, agreeing with Lim that it carries the lesser meaning that Apandi had allegedly by his actions and omissions as the attorney general then exonerated or cleared the perpetrators of the 1MDB scandal including SRC case and covered up the scandal.

In such a situation of not sticking to the strict legalistic interpretation of “aiding and abetting”, the High Court said it would be unhelpful or irrelevant for Apandi to point to the fact — that he had not been charged for the crime of aiding and abetting — in order to prove his defamation lawsuit or for him to dispute Lim’s defence.

In saying that Lim’s statement would carry the lesser meaning of suggesting that there are reasonable grounds for Apandi to be investigated for his actions or inactions during his term as attorney general which may have provided a cover-up for the 1MDB scandal and the suspected persons involved in the scandal, the High Court concluded that these words were defamatory.

The High Court then went on to determine if Lim had succeeded in proving any of his defences.

In short: Yes, it is defamatory. But are any of the defences by Lim proven?

2. ‘Fantastical’ multi-billion ringgit ‘donation’ by still-unnamed Saudi royalty

For Lim to prove his defence of justification, he has to show that his comments on Apandi are either true or substantially true.

The High Court listed four areas of evidence that Apandi had provided in court, including his “perplexingly ‘magnanimous’ decision to exonerate Najib Razak and his bewildering acceptance of the existence of the fantastical ‘donation’ by the unnamed Saudi Royalty even at the face of the fact that RM42 million was already known to have been transferred from SRC’s account (and not any Saudi Royalty account) to Najib Razak’s personal account”.

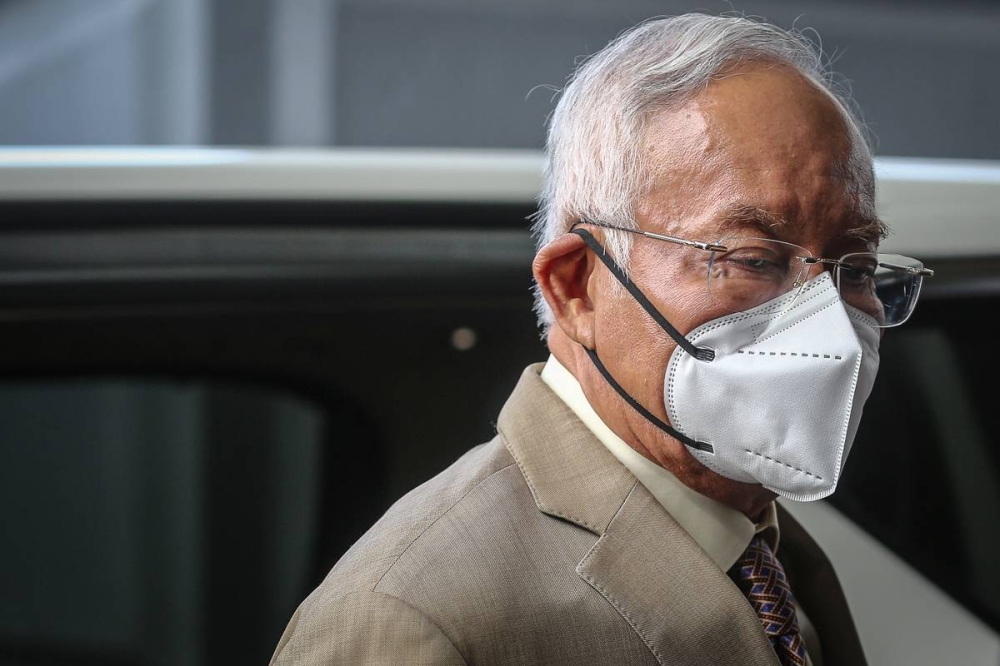

Najib previously maintained that money that came into his bank accounts were a donation from Saudi royalty, but was charged in 2018 and convicted in 2020 over the misappropriation of RM42 million of SRC funds that made its way to his accounts, and is currently appealing to the Federal Court against his conviction.

The High Court judge said Apandi’s decision to clear Najib of wrongdoing and to instead choose the “fantastical narrative of an unproven decision” was the most telling evidence that purportedly showed Apandi’s alleged disinterest and indifference to the rule of law and even common sense.

The High Court expressed its disdain for what it described as Apandi’s own contradictions in his testimony in court as his own witness during the hearing of the defamation lawsuit, his “evasiveness and outright untruth”.

The judge noted that then-AG Apandi had in a January 26, 2016 press conference claimed that the RM2.6 billion paid into Najib’s personal account was a donation from the Saudi royal family, and that Apandi had also claimed the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) had met and recorded statements from the donor who confirmed the monies were donated to Najib privately.

In the same 2016 press conference, Apandi had also said there was no need for Malaysia to seek for mutual legal assistance to complete investigations as there is no criminal wrong, and that there is no criminal wrong in SRC’s RM42 million transfer to Najib’s personal account.

The High Court said Apandi’s 2016 assertion that his delegation had flown to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and personally met with the alleged donor and recorded his personal confirmation of the donation was actually “untruthful”, noting that Apandi had during the defamation lawsuit not only contradicted himself but admitted that the delegation did not even meet nor speak to the alleged donor.

The judge quoted excerpts of the cross-examination of Apandi during the defamation lawsuit where Lim’s lawyer had asked if the delegation could not confirm having actually met with the Prince Saudi, while Apandi answered “I was made to understand that Saudi prince refused to meet anybody.”

The judge said Apandi’s testimony in the court was a “total contradiction”, and that it was indeed suspicious and reasonable to ponder the need to be deceptive about the critical proof of the alleged donation by the Saudi royal family.

“Why would the attorney general bend the truth about meeting and recording a statement by the alleged donor? Why would the attorney general declare to the world that his delegation has met the donor (and obtained confirmation from the donor) while it was well within his knowledge that his delegation did not even speak or meet with the ‘fabled’ donor?” the judge asked.

On this point alone, the judge said it was glaringly obvious that Lim’s remark on Apandi is justified.

“Just for the plaintiff’s untruth about actually meeting the donor, it poses critical questions and grounds for the plaintiff to explain himself under an investigation,” the judge said, referring to Apandi as the plaintiff.

3. Failure to remember alleged donor’s or representative’s name

While having already said Lim’s remark was justified, the High Court judge went on to question Apandi’s “astoundingly indifferent, evasive, deceptive and lackadaisical attitude in pursuing the truth behind the fantastical donation by the unnamed Saudi royalty”.

Citing transcripts of cross-examination of Apandi during the defamation lawsuit, the judge said Apandi chose to depend only on the word of mouth by his delegation instead of direct evidence.

During cross-examination, Apandi had said he “cannot remember” the name of the person who was purported to represent the Saudi prince and who had spoken to the MACC delegation, and also said he “wouldn’t know” if this individual provided any supporting documents to the MACC to support the statement that donation was made by the Saudi royal family.

The High Court also said it was “entirely bizarre” for Apandi to not at least know the name of the purported Saudi prince who allegedly gave the donation, saying that the “memory lapse or even concealment of the donor’s name” has been a constant feature in Apandi’s public statements and even court testimony.

In another excerpt of the cross-examination cited, Apandi told Lim’s lawyers that he “cannot remember the name” of the purported donor but said “it’s just the royal Saudi Arabia family”, and confirmed he could not remember the name of the person who was said to have donated RM2.6 billion to Najib.

The High Court said it was suspicious on how Apandi had “hastily adopted the donation narrative” when he himself as the attorney general “does not even care to remember or to know the name of the fabled donor (which is obviously a critical information for the investigation)”.

The judge asked how Apandi could even determine if the RM2.6 billion was paid by the unknown donor and how there could be meaningful investigation on the alleged donation’s source, if the donor’s name itself is unknown.

The judge said these questions further justify Lim’s remarks that Apandi ought to be investigated, saying that these questionable circumstances also gave rise to suspicion of a cover up or the commission of the cover up.

Among other things, the High Court said Apandi was in the 2016 press conference already aware that some of the funds in Najib’s account were transferred from 1MDB’s former subsidiary SRC and was not a donation from any Saudi royalty accounts at all, based on two flowcharts that Apandi held up then when explaining why he was clearing Najib of wrongdoing.

“Thus, considering the blatantly obvious knowledge of the monies siphoned from SRC to Najib Razak’s personal account, it is suspicious and reasonable to ponder why the plaintiff as attorney general would insist on accepting the donation narrative although the evidence in his own hands and knowledge indicated that the monies were paid from 1MDB’s own former subsidiary, and not at all from any Saudi royalty’s account?

“Why would the plaintiff insist on not investigating the SRC monies further, although the SRC monies trail itself defeats the donation narrative?” the judge asked, and said these questions again justify Lim’s remarks that there are grounds for Apandi to explain himself.

4. The ‘audacity’ of marking the case as ‘NFA/KUS’

While Apandi insisted that his marking of the 1MDB and SRC investigation as “No Further Action” (NFA) or “Kemas Untuk Simpan” (KUS or its literal meaning “arrange for storage”) was never intended to prevent any agencies from further investigation or to reopen the investigation if new evidence arise, the High Court agreed with Lim’s assertion that the “NFA” classification meant Apandi had closed the investigation and had come to a conclusion.

The High Court noted that this was reflected in Apandi’s 2016 press conference when he cleared Najib of wrongdoing at the same time of the investigation’s marking as “NFA/KUS”, saying that Apandi had indicated in 2016 that there was no need for international mutual legal assistance to complete the MACC’s investigation as he saw no wrongdoing in the contribution of over RM2 billion.

The judge pointed out that there would not have been the 2016 press conference and announcement by Apandi of his conclusion that Najib had done no wrong “in receiving the gracious and most fantastical donation in the history of mankind”, if the matter was still under investigation and the investigation has not been closed.

The judge noted that an official who was a deputy public prosecutor in 2016 — who was testifying as a witness for Apandi in the defamation lawsuit — had confirmed recommending to Apandi before the press conference for the case to be further investigated.

The judge noted that a senior MACC official — who was testifying as a witness for Lim in this lawsuit — confirmed Apandi had returned the file with an instruction for “KUS” which is typically given to close the case unless there are subsequent new witnesses which would allow the case to be reopened, and that there were no instructions for any further investigations.

The judge then listed questions that could reasonably be asked and which would also justify Lim’s remark.

“Why would the attorney general hastily NFA/KUS or close the investigation knowing full well that the Riyadh mission was an utter failure and that his delegation had nothing to show to prove the truth of the fantastical donation?

“Why would the attorney general insist on adopting the donation narrative when his own internal task force and even the MACC recommends at the very least, for further investigation, and in fact recommended charges against Najib Razak?”

The judge said Apandi’s action in allegedly “hastily closing and concluding investigations as well as alleged inaction to meaningfully investigate the matter again justifies Lim’s remark which suggested Apandi ought to be investigated for his conducts which may have assisted in the 1MDB scandal’s cover up.

5. Refusing to accept help from Switzerland, US to probe 1MDB scandal

On Apandi’s alleged refusal to accept or offer mutual legal assistance from the Swiss attorney-general or the US Department of Justice (DoJ) to investigate the 1MDB scandal to trace monies that had been siphoned out of Malaysia, the High Court described such refusal as “baffling”.

The High Court noted that Apandi had in the defamation hearing agreed that having mutual legal assistance was necessary to support local investigations in Malaysia, but noted he had also contradicted himself by insisting that such mutual legal assistance from a foreign government or agency would prejudice the local investigation.

Having noted that Apandi’s testimony during the defamation hearing “kept on evolving and whimsically shifting” and that such “fickleness” calls into question his credibility as a witness, the High Court ultimately listed reasonable questions such as why Apandi had refused to accept the Swiss government’s offer of mutual legal assistance when he was fully aware that monies had been siphoned abroad.

“Why was the plaintiff so against the idea of a beneficial cooperative international investigation to unravel the 1MDB scandal and instead preferred to adopt the donation narrative?” the judge said, adding that this too would justify Lim’s remark.

The High Court also said it was reasonable to question why the attorney general would refuse to offer or seek for mutual legal assistance from the DoJ, when it has been aggressively investigating and tracing the 1MDB monies which were believed to have been used to purchase assets in the US.

“Why would the attorney general insist on keeping the investigations localised when he knew well that the 1MDB monies were siphoned out of the Malaysian jurisdiction?” the judge asked.

The High Court ultimately concluded that Lim has proven the full defence of justification.

6. What about the two other defences?

The High Court said Lim had failed to prove his defence of fair comment based on a technical point.

This was because Lim had only briefly said that the matters commented on were of “public interest” and this was insufficient to prove this defence, as he had failed to comply with legal requirements to be more specific by outlining which part of the statement were facts and which part were comments.

The High Court said Lim succeeded in proving his defence of qualified privilege, as it noted that Lim had an interest, duty, legal, social or moral obligation to publish the statement.

“When the 1MDB scandal involves criminalities and illegalities, social and economic repercussions to the nation’s economy, and the morality of the nation’s top leaders and agencies, it is well within the rakyat’s (not just the defendant as member of Parliament) interest and duty, to voice out their dismay and enmity, especially when all avenues of query and complaint have already been exhausted (only for their uproar to fall on deaf ears),” the judge said.

As for the second element required to prove the qualified privilege defence, the High Court noted that the public had a corresponding interest to be informed on all movements and calls against Apandi to explain himself and his actions or inactions which allegedly directly and indirectly helped in covering up the 1MDB scandal and the personalities involved.

In short: Lim proves justification and qualified privilege, fails to prove fair comment defence.

The full 100-page judgment is available here.

What’s next now? Apandi filed on May 24 an appeal against the High Court’s dismissal of his defamation lawsuit against Lim.

The appeal is scheduled to come up for case management before the Court of Appeal on October 5.