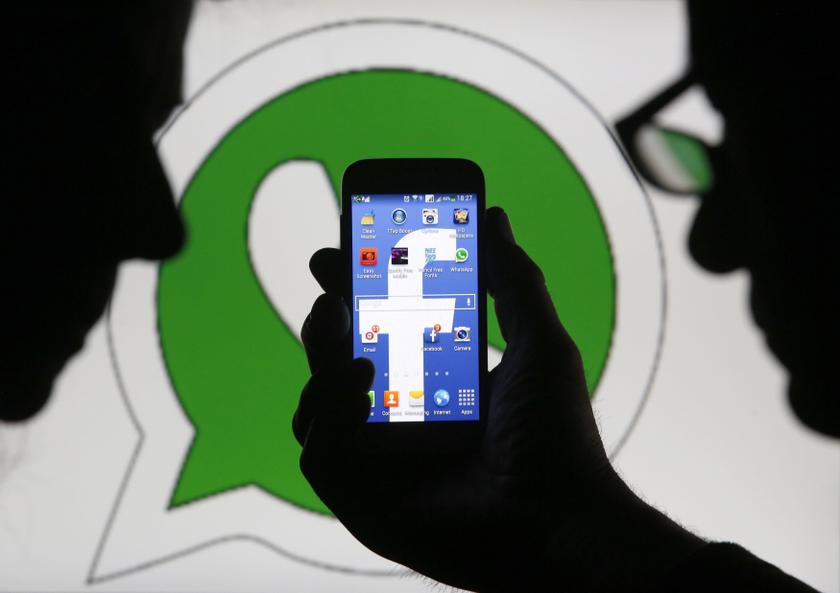

KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 20 — The higher numbers of rural Malaysians owning and using smartphones in 2018 fuelled “subversive” tactics against the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition such as gossip on social media platforms WhatsApp and Facebook, eventually leading to BN’s historic defeat in the 14th general election (GE14), new research has argued.

Researcher Ross Tapsell, director of the Australian National University (ANU) Malaysia Institute, said smartphones were “used extensively to circumvent mainstream media discourse, and as a subversive device for circulating anti-government messages” in the period leading up to GE14.

He noted that Malaysia’s then federal Opposition had in the past managed to win over urban voters but had little success before 2018 in winning over Malay heartland voters who had limited or no internet access, but said smartphones along with Facebook and Whatsapp had by 2018 became more widespread among Malay voters in non-urban areas.

“For all their (serious) flaws around data privacy and the spread of disinformation, Facebook and WhatsApp were common ways that citizens in the rural and semi-rural heartlands of Malaysia received alternative news and views on their smartphones in Malaysia.

“Facebook was the central place to see images of Mahathir at rallies and watching his speeches live, but also for Malaysians to regularly read fervent criticism of prime minister Najib and the Barisan Nasional,” he wrote in a 21-page article that was published in the Journal of Current South-east Asian Affairs.

He was referring to Pakatan Harapan (PH) chairman Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s ‘live’ broadcast of speeches via Facebook when campaigning for GE14.

On the eve of polling day, Dr Mahathir had again relied on Facebook for his final campaign speech, while Datuk Seri Najib Razak had his speech on the same night broadcasted both online and on television channels.

Evolution from GE12 to GE14

Tapsell noted that urban Malaysians have shown great innovation in online campaigning since the internet emerged in the late 1990s, where they used methods such as email lists, alternative news sites, blogging and social media to push for a change of government.

He observed that the past few general elections where BN’s worsening performance was tied to an urban-rural divide, alternative news had greater circulation in the urban areas with greater internet access.

He said BN was itself aware of this, with former prime minister Tun Abdullah Badawi admitting that BN “lost the internet war” in the 12th general election (GE12) in 2008 where it retained power but lost its usual two-thirds parliamentary majority, and also Najib’s declaration in 2013 to urban party campaigners that GE13 would be the “social media election”.

Tapsell further noted that BN lost the popular vote but managed to win GE13 with 133 federal seats, out of which 108 were categorised as “semi-rural” or “rural” seats; while the then federal Opposition won in big cities, especially within and around capital city Kuala Lumpur.

Tapsell said the 2013 results actually reflected an “urban tsunami” against the then BN-led government, as opposed to Najib’s controversial claim of a “Chinese tsunami”.

The GE14 strategy and what changed

Tapsell said the then federal Opposition PH was expected to continue to win huge support in GE14 from urban, non-Malay votes, and that its strategists had planned to cause a “Malay tsunami” by winning over Malay heartlands, mostly in peninsular Malaysia, and to capture 100 out of 112 federal seats there.

Tapsell observed that there were “broad signs of a more fractious and disgruntled Malay electorate by now existing” in the run-up to the GE14 polls in 2018, contrasting it with 2013.

“One big difference in these communities between 2013 and 2018 was internet access via the smartphone,” he said, citing a 2017 news report when saying Android smartphones churned out by China made them more affordable for middle-class and low-income Malaysians to own.

Citing other reports, Tapsell said around 10 million smartphones were sold in Malaysia in 2017, while the government spent RM7 billion on subsidies for smartphone imports which Najib had felt was a “necessity”.

He noted the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission’s (MCMC) 2012 figures that 77 per cent of Malaysian adults had internet access, while only 24.2 per cent of rural voters had internet, in comparison to 2017 where rural areas saw a huge growth to 57 per cent in comparison to urban areas that maintained their internet access levels.

“In short, internet access had doubled in the rural areas of Malaysia since the previous general election,” he said, noting that the growth in Malay semi-rural and rural areas was crucial.

“Prior to the last elections in 2013, only around 58 per cent of internet users were ethnic Malay. In two years, that number had grown to 68 per cent (MCMC 2018) — and continued to increase going into election year too.

“This growth allowed for online information dissemination into areas where previously the newspaper and television station had dominated,” the senior lecturer at the Department of Gender, Media and Culture at ANU’s College of Asia and the Pacific added.

Citing MCMC figures, Tapsell said over 70 per cent of Malaysians had internet access by 2018, with around 90 per cent of them using a smartphone, and with 90 per cent of smartphone users using it to obtain information.

He also cited the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism’s 2018 report that found 72 per cent received their news via social media, while 77 per cent used the smartphone as a device for news. The same report showed Malaysians who received news via Facebook and WhatsApp stood at 64 per cent and 54 per cent respectively.

Subversive tactics

In examining why PH won the election, even though all parties had ramped up social media efforts for GE14, Tapsell noted that a member of Najib’s GE14 social media campaign team had told him post-GE14 that PH were better at making WhatsApp content that went viral organically due to the emotions that it stirred up, as compared to the BN campaign material which was more similar to traditional media.

Tapsell, who was “embedded” in numerous local WhatsApp groups during GE14, observed that Malaysians had subversively shared “gossip” on Najib and his wife’s purported wealth that was allegedly linked to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) corruption scandal.

While mainstream media coverage of the 1MDB scandal was repressed, Tapsell said stories on the issue were shared regularly on Facebook and WhatsApp, with some either citing the stories as proof of a cover-up by the Malaysian government or to claim that foreign media were biased and using 1MDB to attack the Malaysian government.

“While there was a general belief in Malaysia that the details of 1MDB were too complex to resonate in rural towns and villages, the message of government corruption was clearly spread far and wide,” he said, noting that locals in Kedah had told him they received the information via WhatsApp or Facebook.

Tapsell noted that despite the Najib administration’s hasty enactment of the Anti-Fake News Act in the lead-up to GE14, Malaysians had continued to share anti-government messages with the subversive tactic of “feigned ignorance” such as by adding disclaimers and asking others to verify the information.

“In the digital era, weapons of the weak in Malaysia included gossip, rumour, conspiracy, feigning ignorance, generating uncertainty, casting doubt and subverting state authorities — all predominantly done digitally, through smartphones, social media platforms and chat applications,” Tapsell said.

Unlike typical analysis of regime change often framed as “social media revolutions” where alternative news sources lead to spontaneous street protests and a fervent democratic revolt, Tapsell said Malaysia’s previous regime was not brought down by a spontaneous online movement but was “defeated peacefully through the ballot box after numerous previously close attempts” through online subversion.

Tapsell cautioned, however, that the GE14 results should not necessarily be viewed as a victory for democracy, noting that the nationwide voting out of the Najib-led BN was also broadly linked to the rising cost of living and bread-and-butter issues such as taxes including the Goods and Services Tax (GST).

Tapsell’s research piece titled “The Smartphone as the ‘Weapon of the Weak’: Assessing the Role of Communication Technologies in Malaysia’s Regime Change” was accepted for publication on November 21, 2018.

His research from February 2018 to July 2018 was based on various sources, including interviews with key social media campaign professionals and strategists from both sides of the political divide, fieldwork in Kedah to research semi-rural communities, and scrutiny of messages running into up to 250,000 words from the multiple WhatsApp groups from April 19 until polling day in 2018.