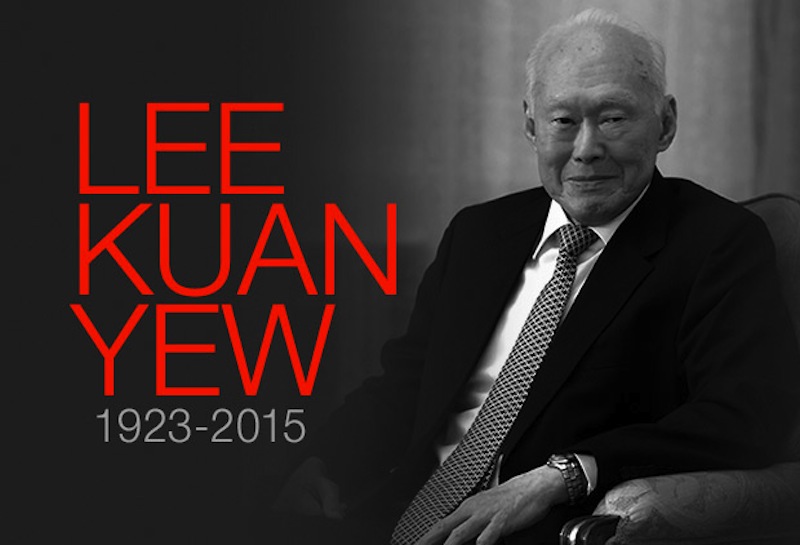

SINGAPORE, March 23 — Over his lifetime, Lee Kuan Yew had to sing four national anthems: British, Japanese, Malaysian and finally Singaporean. This reflected the progression and momentous events of his life that shaped him into the leader he became. The Japanese Occupation and life as a student in Britain profoundly shaped his view of the world and human nature, while the political struggle for power and self-government honed his leadership style and tactics.

But it was in the pre-war years that Lee’s initiation into the politics of race and religion took place.

With World War II raging in Europe in 1940, Lee, who had planned to read law in London, took up a scholarship to study at Raffles College instead (after having come in first in Singapore and Malaya in the Senior Cambridge examinations).

It was at Raffles College that he encountered Malayism, “a deep and intense pro-Malay, anti-immigrant sentiment” among indigenous Malays who had been given special political and economic rights, and who feared being overwhelmed by hard-working Chinese and Indian immigrants.

Coming from the Malayan states, their attitude contrasted with that of the Singapore Malays, who were accustomed to equal treatment in a British colony that made no distinction among the races.

It was also at Raffles College that Lee formed lasting friendships with some who would later be close political colleagues, including the late Toh Chin Chye and Goh Keng Swee, then a tutor in economics.

The Japanese occupation

The Japanese invasion in December 1941 disrupted studies at Raffles College and heralded the most important foundational years of Lee’s life.

The Japanese had shattered the colonial system and the myth of British superiority — the idea that, as many had believed; the British empire would last a thousand years. “We literally saw a whole society disintegrate — it collapsed overnight. And we were serfs, to be trampled on, to do the Japanese’s bidding. And that did something to a whole generation; we said, ‘No! Why? This is my life, my country! I have something to say!’”

The Japanese were cruel, unjust and vicious. In his first encounter with a Japanese soldier, Lee was slapped, made to kneel and sent sprawling with a boot. He worked as a clerk, as a transcriber for the Japanese, and ran his own businesses (such as manufacturing glue) to survive.

The Japanese Military Administration governed by fear. Punishment was so severe that crime was very rare, at a time when people were half-starved with deprivation. “As a result I have never believed those who advocate a soft approach to crime and punishment, claiming that punishment does not reduce crime,” Lee said.

The Occupation was his first lesson on power, government and human reaction, he said. “I learnt more from the three-and-a-half years of Japanese Occupation than any university could have taught me. I had not yet heard Mao’s dictum that ‘power grows out of the barrel of a gun’, but I knew that Japanese brutality, Japanese guns, Japanese bayonets and swords, and Japanese terror and torture settled the argument as to who was in charge, and could make people change behaviour, even their loyalties.”

Student life in England

After the war, Lee pursued his law studies in England. It was there, in the late 1940s, that he came to seriously question the continued right of the British to rule Singapore.

He was treated roughly as a colonial by some landladies and shopkeepers, treatment he resented from social inferiors. “And I saw no reason why they should be governing me; they’re not superior. I decided, when I got back, I was going to put an end to this.”

He took part in a discussion group called the Malayan Forum, which pressed for an independent Malaya and a non-violent end to British rule. Its members included Dr Toh and Dr Goh, as well as Tun Abdul Razak, who would later become Prime Minister of Malaysia.

Lee’s time in Britain also helped form his initial political philosophy.

In his first term at the London School of Economics — before he transferred to Cambridge, where he graduated with double first-class honours — Lee was introduced to the general theory of socialism in political scientist Harold Laski’s lectures. He was immediately attracted to it.

“It struck me as manifestly fair that everybody in this world should be given an equal chance in life, that in a just and well-ordered society there should not be a great disparity of wealth between persons because of their position or status, or that of their parents,” he said.

But he would later alter his views on Fabian socialism. “They were going to create a just society for the British workers — the beginning of a welfare state, cheap council housing, free medicine and dental treatment, free spectacles, generous unemployment benefits. Of course, for students from the colonies, like Singapore and Malaya, it was a great attraction as the alternative to communism.

“We did not see until the 1970s that that was the beginning of big problems contributing to the inevitable decline of the British economy.”

PAP and the fight for self-government

Returning home to Singapore in 1950, Lee continued to witness the “injustice” of a whites-on-top society.

“You might be a good doctor, but if you are an Asian, you would be under a white doctor who’s not as good … The injustice of it all, the discrimination, struck me and everybody else,” he said. This was a lesson that stayed with him when, later, he set up a merit-based, race-neutral Civil Service in independent Singapore.

Lee started work at a law firm and became legal adviser to several trade unions.

In 1952, when negotiations between the Postal and Telecommunications Uniformed Staff Union and the government failed, the union carried out the first strike since Emergency Regulations were introduced in 1948, upon Lee’s reassurance that this was not illegal. The publicity enhanced his reputation.

Lee and his coterie, which included S Rajaratnam and Dr Toh, became convinced that the unions could serve as the mass base and political muscle they had been seeking. He linked up with left-wing Chinese-educated unionists such as Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan in 1954. And the People’s Action Party was launched on Nov 21 that year — born out of a marriage of convenience with the pro-communist trade unionists.

The next year, the PAP won three of the four electoral seats it contested; Lee won the Tanjong Pagar seat with the largest number of ballots cast for any candidate, and by the widest margin.

But as the party’s mass base continued to expand considerably, the Malayan Communist Party set out to capture the People’s Action Party (PAP) itself.

In August 1957, during the party’s third annual conference, pro-communist elements managed to win half the central executive committee seats. However, five were detained during a government security sweep — and Lee and his colleagues took the opportunity to create a cadre system, where only cadres could vote for the CEC and only the CEC could approve cadre membership.

In later years, Lee would say of learning to be a streetwise fighter in the political arena: “I would not have been so robust or tough had I not had communists to contend with. I have met people who are utterly ruthless.”

Merger and defeating the pro-communists

The British finally agreed to self-government for Singapore (except in matters of defence and foreign relations) — and Lee became Prime Minister of Singapore at the age of 35, when the PAP captured 43 of the 51 seats in the Legislative Assembly elections of May 1959.

But still, the pro-communists were growing in strength among the unions, and Lee could not simply move against them without losing the support of the Chinese-speaking workers.

Union with Malaya thus provided the “perfect issue” on which to force a break with the party’s left-wing elements, which were opposed to the merger. After a vote of confidence was called in 1961 — a vote Lee’s government barely won with 26 votes out of 51 — several assemblymen broke away to form the Barisan Sosialis.

The months that followed were the toughest, most exhausting fight for political survival yet for Lee, against adversaries he later described as “formidable opponents, men of great resolve”.

Bringing the battle with the pro-communists fully out into the open, he campaigned at the grassroots, speaking daily in Malay, English and Chinese; and did a series of 12 radio broadcasts on the battle for merger, arguing why Singapore needed the hinterland for its economic survival.

When the merger referendum was held in September 1962, the PAP carried the day — 71 per cent of votes went to the form of merger that Lee had campaigned for.

On August 31, 1963, Lee declared Singapore’s independence from British rule and, on his 40th birthday on Sept 16, Singapore merged with the Federation of Malaya, Sabah and Sarawak to form Malaysia.

Into the fire of Malay communalism

The merger would prove to be short-lived — a costly experience that brought into violent conflict the two major races in Singapore, as well as the PAP and the Federal government. As Lee put it, the party “had jumped out of the frying pan of the communists into the fire of the Malay communalists”.

The United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) leaders were determined to maintain total Malay supremacy. They were worried by the inclusion in the Federation of Singapore’s Chinese majority and that the PAP might make inroads in Malaysia — for Lee openly and strongly opposed the bumiputra policy, calling for a “Malaysian Malaysia” where Malays and non-Malays were equal.

UMNO leader Syed Ja’afar Albar’s stoking of racial flames reached a watershed during the race riots of July 1964. The Singapore Government’s memorandum that later set out the events leading to the riots concluded that those in authority in Kuala Lumpur did not restrain those indulging in inflammatory racist propaganda.

In September, a second wave of racial riots erupted in Singapore. And by December 1964, both sides were groping towards a looser arrangement within the Federation. While Lee tried to find a compromise with Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, the latter became more and more sold on total separation.

Goh Keng Swee eventually convinced Lee that secession was inevitable — which was a heavy blow to Lee, who believed Singapore’s very survival lay within Malaysia.

A moment of anguish

On Aug 9, 1965, in a televised press conference, Lee fought back tears as he formally announced the separation and the full independence of Singapore, saying: “Every time we look back on this moment when we signed this agreement which severed Singapore from Malaysia, it will be a moment of anguish. For me, it is a moment of anguish because all my life ... you see, the whole of my adult life ... I have believed in merger and the unity of these two territories.”

But he and his team were determined to make Singapore succeed, despite the odds — and that in building the foundations for a new country, they would never forget what came before. “I would like to believe that the two years we spent in Malaysia are years which will not be easily forgotten, years in which the people of migrant stock here who are a majority learnt of the terrors and the follies and the bitterness which is generated when one group tries to assert its dominance over the other on the basis of one race, one language, one religion,” Lee said in 1965.

“It is because of this that my colleagues and I were determined, as from the moment of separation, that this lesson will never be forgotten.” — TODAY