MARCH 30 — When China first alerted the World Health Organisation (WHO) about the new coronavirus Covid-19 on December 31, 2019, it was already growing at an alarming rate.

Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and soon the rest of China, struggled in the battle to fight the virus — as the world watched, and condemned the nation.

Fast forward to three months later, Covid-19 has spread to more than 170 countries and territories, infected more than half a million people and caused the deaths of more than 30,000 patients.

How are countries dealing with the coronavirus?

Countries globally are putting various measures to combat the health crisis, which WHO declared a pandemic on the March 11, 2020.

China leveraged on its advanced technology capacity especially the Artificial Intelligence (AI) sector to assist the efforts to combat Covid-19.

For instance, AI is used to assess measures, provide suggestions and early warning signals, predict potential virus hosts as well as to support drug discovery.

Thailand repurposed “ninja robots” machines to facilitate communications between doctors and coronavirus patients through video chat functions to reduce the risk of infection.

South Korea used drones to spray disinfectants in coronavirus hot spots.

In Taiwan, its digital policing approach leveraged on big data analytics — integrating its national health insurance database with immigration and customs databases.

The role of technology amidst Covid-19

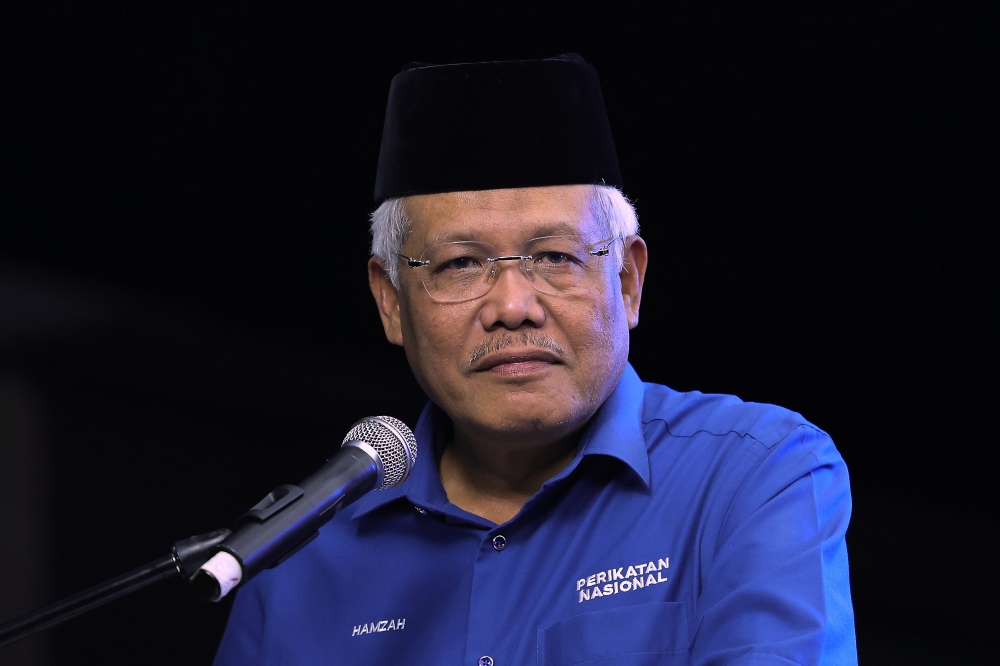

In Malaysia, the new Perikatan Nasional government implemented the Movement Control Order (MCO) which has currently seen an estimated 95 per cent compliance rate.

In this period where the majority of the people had to stay at home, the growing role of technology in the lives of Malaysians is immediately observable.

Without face-to-face interactions, conference calls are needed to carry out work from home while e-learning is utilised to ensure continuity of students’ education.

Even artists are performing "live" online with instructors delivering workout instructions on YouTube for online viewers, all of which are fast becoming a norm.

While some say that this crisis is forcing citizens to rely on technology much more than usual, others see technology as a means for people to continue their daily tasks amid the disruption faced.

For instance, while it was first announced that courts will be closed for the duration of the MCO, the extension of the MCO encouraged the Malaysian judiciary to take the bold step of conducting virtual hearings.

Technology has also been leveraged to assist the battle against the virus.

Drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) are being mobilised to assist law enforcement to monitor public compliance.

Further, according to Khairy Jamaluddin, the newly-minted Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation (Mosti), an app is being built to “alert people who have been exposed to those infected with Covid-19, an important mitigation strategy post MCO.”

The state of Sarawak, on the other hand, rolled out a digital surveillance system which requires monitored people to wear a QR-coded wristband to control the spread of Covid-19 at all of Sarawak’s Points of Entry (POEs).

Potential arising threats

While technology can assist us in times of disruption, they can also serve as a conduit that takes advantage of the crisis.

Cyber-attacks exploiting Covid-19 fears were observed in various locations including India, Czech Republic and Italy.

A study by Cynet discovered a correlation between the increasing Covid-19 infection cases in Italy and the rising cyber-attack cases targeting work-from-home employees — where 35 per cent of personal emails encountered cyber-attacks.

In Malaysia, just a week after the MCO started, scammers used social media to trick citizens regarding government aid and online sales of face masks — incurring RM3 million in losses.

Moving forward, the government, industry and society need to collectively collaborate to break these attempts.

Adding to that, disinformation and misinformation are putting additional strains on efforts to combat the coronavirus.

Financial damage, promotion of misleading and dangerous guidelines, public panic and elements of racial discrimination are some of the impact of false information spread.

Although the Anti-Fake News Act had been repealed in December 2019, efforts to combat false information need to be continued through increasing digital literacy skills, heightening the responsibility of social media platforms, creating robust fact-checking mechanism and putting appropriate legislation in place.

Lastly, as Malaysia follows the footsteps of several countries to ramp up the use of surveillance through tracking devices for instance, we must also bear in mind the concerns of ethics and privacy that come with it.

While we may be more familiar with the consequences of interested parties monitoring our online behaviour, through these new technologies, such parties may now have access to our offline information — body temperature, blood-pressure, current and past locations, who we met and so on and so forth.

This pandemic could mark the start of a terrifying surveillance system that invades the privacy and human rights of citizens, if left unchecked and abused by irresponsible parties.

Imagine your biometric data being monitored, your feelings being predicted and manipulated — what happens when it’s in the wrong hands?

What happens post-MCO?

When the fight against Covid-19 ends, one might wonder how much change do we need to adapt to, endure and embrace?

Professor Yuval Noah Harari also argues that “...the storm will pass, humankind will survive, most of us will still be alive — but we will inhabit a different world.”

He also reminds us that “many short-term emergency measures will become a fixture of life.”

Hence, when this global crisis ends, would we be immersed in the use of technology as much as we did during times of isolation?

Will we continue to minimise human contact? Will we allow ourselves to be monitored through high-tech surveillance systems and will mass gatherings be substituted by Virtual Reality (VR) instead?

The world after the coronavirus may look like the “future” depicted in movies and science fiction books. But the world we live in now still struggles to survive, and adapt to the sudden new way of life.

For the Muslim majority in Malaysia, the holy month of Ramadan is a much anticipated time of the year, followed by a month of feasting and celebrations.

As the number of infected cases and deaths continue to rise, the uncertainty of when the MCO might actually end lingers.

The prospect of this war ending soon seems unlikely. Ramadan is approaching in less than a month, but it is unlikely that we will be able to experience it like in previous years.

There will be empty streets. Empty restaurants. Empty mosques.

When Syawal arrives, perhaps donning Hari Raya outfits while video-calling friends and family afar may be the best case scenario.

* Dr Moonyati Yatid is a senior analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.