KUALA LUMPUR, April 18 — The Malaysian government’s 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) acted as if it was giving money away for free when it “invested” its billions of ringgit, as its purported investments were actually classic examples of “sham” or fake investments, a former banker in Singapore today told the High Court in Kuala Lumpur.

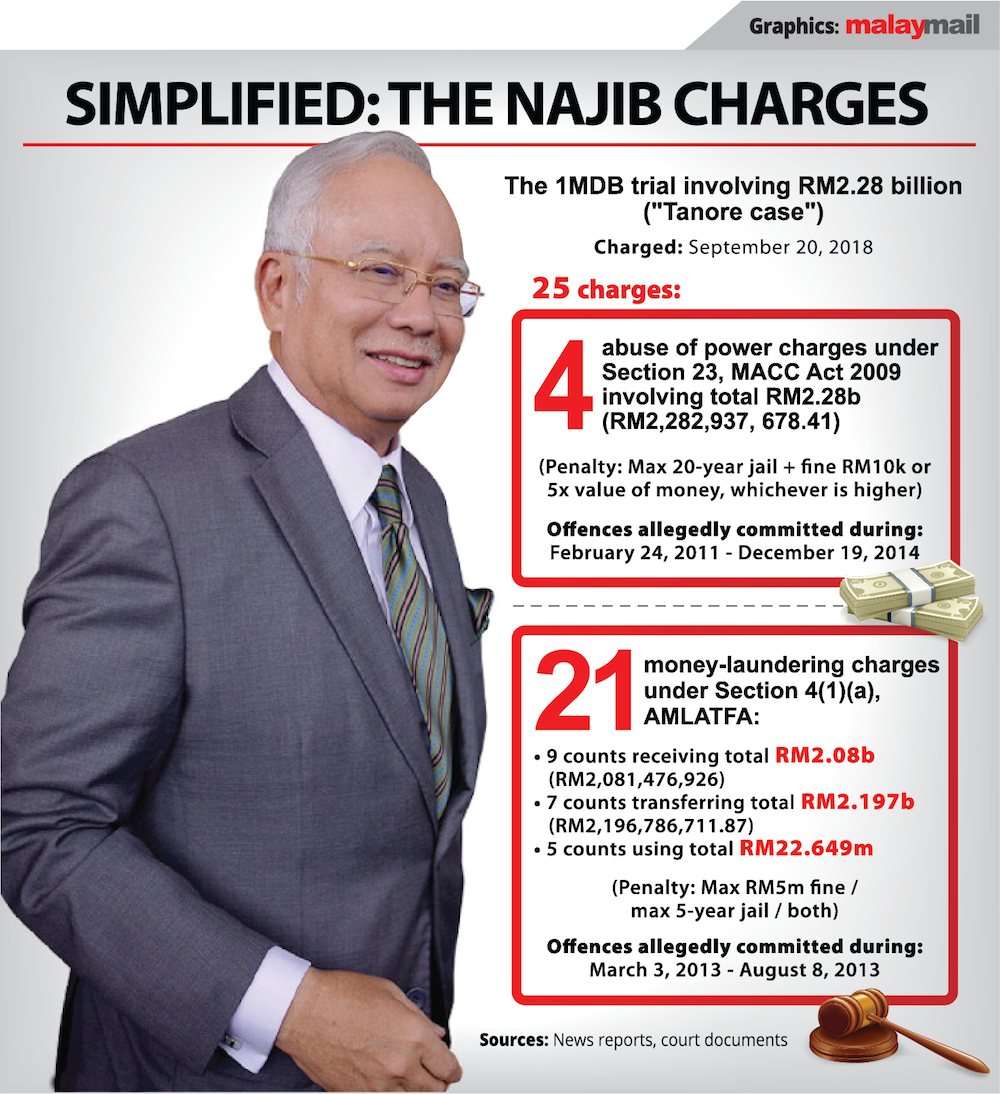

Kevin Michael Swampillai, a Malaysian who previously worked in the BSI Bank in Singapore where 1MDB companies had bank accounts, said this during former prime minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak’s trial over the misappropriation of RM2.28 billion of 1MDB funds.

Swampillai is the prosecution’s 44th witness in the trial, where 1MDB’s RM2.28 billion funds were alleged to have been deposited into Najib’s private bank accounts.

In this trial, Swampillai testified about 1MDB subsidiaries — 1MDB Energy (Langat) Limited (1MELL) and 1MDB Global Investment Limited (1MDB GIL) — which had sent out money from their bank accounts to the BSI Bank in Singapore, to be passed on to the bank accounts of “fiduciary funds” to help invest the money, and selected “target companies” which would “borrow” money from the fiduciary funds.

But Swampillai said that these purported investments were not real at all, as the money which left 1MDB and was passed around different bank accounts of different companies would never make it back to 1MDB.

Unlike typical investments such as fixed deposits or in stock markets where the investor still has “complete control” and could withdraw or liquidate those investments, Swampillai said 1MDB subsidiaries could not easily take back the invested sum as they were no longer in control of their funds once it left their accounts and entered the fiduciary funds’ accounts.

While 1MDB subsidiaries tried to “invest” by putting their money into fiduciary funds, the fiduciary funds would give out the money as loans to companies. In exchange for giving out loans, the fiduciary funds would receive “promissory notes” from the companies.

But Swampillai said these “promissory note” agreements were not a genuine loan, since the documents did not mention any dates when repayments would be made and did not mention the interest rate at which the loans would be repaid.

“The only principal piece of document that would indicate whether these clients would make any money would be the promissory notes documents. As I said, no economic value inherent in those documents, no interest rate, no promise to be paid, it looks as if they were giving money away for free,” he told the High Court during cross-examination.

Swampillai agreed with Najib’s lead defence lawyer Tan Sri Muhammad Shafee Abdullah that these promissory notes looked “empty” and that these documents were “empty promises”.

Swampillai said he had always felt “discomfort” over transactions involving 1MDB and its group of companies from “day one” itself, based on the structure of the transactions with “sham” promissory notes, as well as the use of layering techniques which are typically seen in money laundering to hide the identity of where the funds came from.

“My discomfort did not change, it was always there, it didn’t come up specifically to 1MDB Global Investment Limited (1MDB GIL), because it was the same, at the back of my mind, I always felt these transactions were shady to say the least,” he said.

Textbook example of sham transactions

In 1MDB GIL’s case, it received US$2.721 billion on March 19, 2013, in its BSI Bank account, and the very next day sent out over US$1.59 billion to three fiduciary funds — Enterprise Emerging Markets Fund (EEMF), Cistenique Investment Fund (CIF) and Devonshire Funds Limited — to “invest”.

The three fiduciary funds then transferred over US$1.26 billion to Granton Property Holding and Tanore Finance Corporation as “loans”, backed by the promissory notes which Swampillai said was a sham.

If 1MDB GIL directors had looked at these promissory notes, it would have been “patently clear” to them that there was no obligation for Granton and Tanore to repay and that there was actually “no promise to pay” in these documents, Swampillai said. He said this would be a “textbook example” of a sham transaction.

Another 1MDB subsidiary, 1MELL also went through a similar process, where its US$790 million was sent to the BSI account of Aabar Investments PJS Limited — a company registered in the British Virgin Islands and now known to be a fake company modeled after the actual Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund Aabar Investments PJS — before being sent to fiduciary funds like EEMF and CIF and which then ended up at Blackstone Asia Real Estate Partners Limited. There was again a promissory note involved in the process.

Swampillai gave his opinion that this flow of money out from 1MELL would not have happened if the company’s directors had used common sense and carried out due diligence to check the documents and done their jobs properly, as all they would have to do is “scratch the surface” as all sorts of red flags would jump up and there would be sufficient reasons not to proceed.

Swampillai said it is BSI’s clients — the 1MDB group of companies — which decides on which fiduciary funds and which target companies to use for these transactions.

Noting that governments typically set up sovereign wealth funds to invest public funds to benefit the country’s citizens, Swampillai said that it would be “highly unusual” for sovereign wealth funds to conceal their identity and there would be no need and no reason to hide it if they were investing openly and transparently.

Ex-banker denies knowing 1MDB funds being misappropriated

But when Shafee suggested that Swampillai and other BSI bankers had acted “in concert” with Low Taek Jho, 1MDB officials and the fake Aabar’s officials to misappropriate US$790 million from 1MELL, this was denied by Swampillai who was head of wealth management services in BSI then.

“So from my perspective, was I involved with others in concert with misappropriating money? Answering purely from my perspective, there was no element of foreknowledge on my part. I just executed these transactions according to the instructions given to me and the expectations that were placed on me as head of the department that would typically undertake these transactions.

“So no element of foreknowledge, so I would say categorically I wasn’t involved in any misappropriation or acting in concert with those people. However I cannot speak for others involved in the transactions, some of my colleagues went on to develop closer relationships with Jho Low. Yak Yew Chee was the relationship manager, Yeo Jiawei went on to work with Jho Low at some point, so I cannot speak to their level of knowledge, level of intimacy they developed with regard to inner going-ons with regard to these transactions,” he said, adding that he would not be able to say if there were elements of Low working in concert with some of the BSI bankers.

Swampillai said he had met Low thrice — once in Singapore and twice in Kuala Lumpur, but said he did not realise throughout those meetings that the money flowing to Blackstone was actually misappropriated from 1MELL.

While saying that BSI did not act on red flags on the 1MDB group of companies, Swampillai said he believed that no one in the bank’s compliance department or senior management knew the money was being misappropriated, but suggested that it was possible they had misgivings over the transactions.

“And this is based on my experience, because I always retained a certain amount of scepticism relating to these transactions, they didn’t seem right, and I wouldn’t discount the fact that many other people in BSI Bank had the same opinion as well,” he said.

Swampillai said Low — who is better known as Jho Low — was consistently positioned to be the enabler and adviser to the 1MDB group of companies, citing this “murky” claim for his assumption that Low was “omnipresent” to all these dubious transactions involving 1MDB-linked companies as he was their adviser.

On the first day of trial, the prosecution had said it would show that 1MDB took on debt to raise funds which were placed in 1MELL, before these 1MDB funds worth US$790 million were passed to the fiduciary funds and also made their way to Blackstone, and with Blackstone then allegedly passing US$5 million and another US$25 million into Najib’s personal bank account in October and November 2012.

The prosecution had also said it would show that the US$2.721 billion of 1MDB GIL’s funds were obtained by taking on debt, with part of these funds being sent to fiduciary funds and then passed on further to Granton and Tanore, with Tanore allegedly transferring US$681 million (equivalent to over RM2.081 billion) to Najib’s bank account.

Najib’s 1MDB trial before Judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah is scheduled to resume on May 8 to May 11, with Swampillai scheduled to continue testifying.