KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 21 — With Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob and his ministers temporarily taking care of the government’s day-to-day operations until Malaysia gets a new government in the 15th general election (GE15), can they announce goodies to voters and brandish the yet-to-be approved Budget 2023 in their caretaker role?

Would the caretaker prime minister and his caretaker ministers run the risk of breaking any election laws, if they highlight Budget 2023 points, or make announcements before polling day on November 19?

Or will it just be a breach of convention, or the way things are usually done by caretaker governments?

Here’s what constitutional lawyers contacted by Malay Mail think:

Caretaker PM can’t make policy or budget commitments

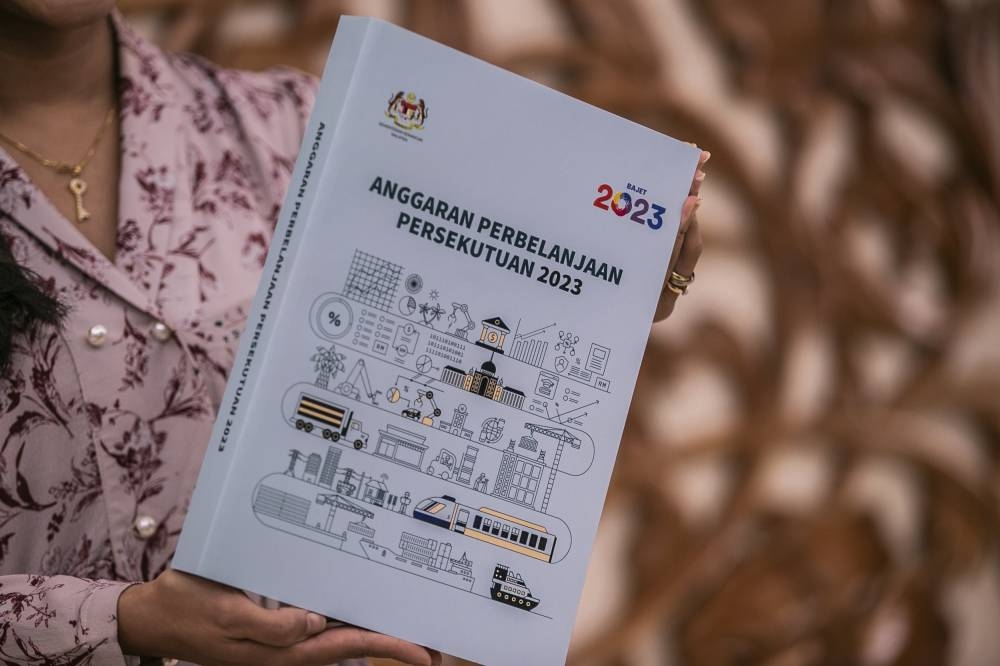

Constitutional lawyer Datuk Gurdial Singh Nijar pointed out that a budget for the government needs to be approved by Parliament, and that the proposed Budget 2023 which was presented in the Dewan Rakyat on October 7 was not approved.

“Strictly, there is no longer any Budget in existence. The party that wins will have to table a new Budget, and that will go through the debate and approval process. So it is wrong for the PM to claim that the Budget will be implemented.

“A caretaker PM cannot make any firm policy and other commitments,” he said.

Gurdial was giving his response after being shown news reports where Ismail Sabri had on October 17 said that funds were available for Budget 2023 that was just waiting to be passed, with the latter also reportedly saying on October 16 at a Bera Umno event: “If you want the Budget to be implemented, vote for us and then (the Budget) can be re-tabled and approved.”

Gurdial also said such commitments cannot be made by those in caretaker roles, as it is yet to be known what the new government would look like.

“We do not know the nature and configuration of the new government. Hence, it is meaningless to make a firm commitment of policy, etc. Same applies to the commitment to table the same Budget,” he said.

“He is in no position to make a firm commitment. His is only an aspirational statement, and a pledge, no more and no less. It is a political proclamation which has no binding effect and should be treated as such,” he added when referring to Ismail Sabri’s remarks.

Gurdial agreed that Malaysia needs a law for caretaker governments, saying: “Yes, there is a need to have a law to prescribe the parameters of what a caretaker government can do.”

No guarantee of same Budget 2023 after GE15

Andrew Khoo, the co-chair of the Bar Council’s Constitutional Law Committee, highlighted the difference between actual government policy and an electoral promise.

Commenting on Ismail Sabri’s remarks regarding the yet-to-be passed Budget 2023, Khoo said: “The Budget, since it was never debated and passed in Parliament, is an election campaign gimmick. There is no guarantee that the exact same Budget will be reintroduced once the new Parliament is convened following the general election. We are not even certain Ismail Sabri will be the prime minister in the next government.”

As for caretaker health minister Khairy Jamaluddin’s similar remarks on October 11 that Budget 2023 which was tabled earlier this month features government expenditures that have already been allocated, Khoo said: “Resources may have been identified but to say that they have been allocated cannot be correct, unless the minister is admitting that the government is used to a practice of actually allocating resources even before a Budget has been passed.

“They can certainly prepare for one, but it cannot be implemented until the Budget is passed and it becomes law, and the new financial year has begun. And since Parliament has been dissolved, everything is on hold,” he added.

“During the caretaker period, the caretaker government should not be talking about its Budget proposals,” he said.

Khoo stressed that a caretaker government should not talk about “policy proposals” as it would “breach neutrality and impartiality”.

Khoo noted that the Election Commission (EC) has in the past taken the view that election offences can only occur during an election campaign period.

“So they have not looked into election promises uttered before the start of the campaign period. This may not be correct,” he said.

“In any event, making funding promises before the start of the election campaign would be a breach of the convention relating to caretaker government. Sadly, there is no penalty for that, save at the hands of the voters themselves,” he added.

Khoo believes Malaysia needs a law for caretaker governments, saying: “Especially since penalties can only be imposed through a law passed by Parliament.”

“It is important that there should be no abuse or misuse of the position of incumbency during a period between the dissolution of Parliament and the convening of a new Parliament. At the very least, we need protocols that have been impartially drafted and publicly disseminated,” he said.

Actually, what is a caretaker government?

Human rights and constitutional lawyer Nizam Bashir said the Federal Constitution does not contain the phrase “caretaker government”, explaining that it is simply a parliamentary or constitutional convention. Or in other words, “rules of constitutional practice” that are generally regarded as not legally-binding but binding in operation.

He said countries with a Westminster system of government like Malaysia tends to lean towards the “zombie” model for caretaker governments, which is one “asleep at the wheel that is incapable of taking or making any major decisions/politically ‘heavy’ questions”.

But he said the true limits of a caretaker government is decided on a case-by-case basis, where major decisions could be made in urgent situations.

“This can be seen for example from the then Mahathir-led caretaker government announcing a RM20 billion financial stimulus package in February 2020 to tide the country over when it was in its early throes of the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said.

But without urgent circumstances which would justify a caretaker prime minister continuing to make announcements of goodies or allocations or projects after Parliament has been dissolved, Nizam said this may be contrary to the principles of a caretaker government.

Asked what would happen if a caretaker government breached the caretaker convention, Nizam said it could result in political consequences such as heavy criticism or occasionally even loss of respect or popular support.

While noting that flexibility may not be necessarily problematic as it could provide room for caretaker governments to make judgment calls based on the situation, Nizam said some principles could still be formulated, citing the United Kingdom and New Zealand as examples.

Noting that the UK’s 2011 Cabinet Manual does not have the term “caretaker government”, he referred to the “Restrictions on government activity” section, including Paragraph 2.27 where such governments are expected to ensure that “essential business” continues, while observing discretion in starting any new long-term action immediately before an election.

He also referred to New Zealand’s 2017 Cabinet manual which specifically mentions “Principles of the caretaker convention”, especially Paragraphs 6.25 and 6.29 which also sets out what caretaker governments should do.

“We do not have to reinvent the wheel,” Nizam said when asked if Malaysia needs its own set of dedicated law, pointing out that the EC had in September 2012 announced it has a draft code of conduct for a caretaker government based on studies on other Commonwealth countries.

“Perhaps we can start by simply looking at what we already have as opposed to proposing new ones to codify or enact,” he said.

Nizam said the duration of a caretaker government lasts from when a government is dissolved until a new administration is appointed after a general election, or from when the government has clearly lost the confidence of MPs until a new administration is appointed.

Khoo said a caretaker government’s period would end only after a new government is sworn in after a general election, but noted that there are some who argue that the period runs up to when Parliament begins sitting as “until MPs take their oath of office before Parliament begins, they are not yet MPs.”

“So a law that clearly defines the period of caretaker-ship would be helpful,” he said.

As to what caretaker governments can do, Khoo said: “The common and conventional understanding is that a caretaker government should merely carry on with the ordinary administration of government, and should not change existing or make new policies, announce new spending proposals, or undertake new initiatives.

“They should maintain the status quo and hand over the reins to the new government once it is formed after the general election,” he added.

Canada’s guideline for the conduct of ministers during an election says caretaker governments should limit themselves to actions that are “routine, non-controversial, urgent and in the public interest, reversible by a new government without undue cost or disruption”. Australia too has a guideline on caretaker conventions.

What are the possible election crimes?

Nizam said various laws in Malaysia could be looked at to address alleged “vote-buying” such as the Penal Code, the anti-money laundering law, and the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act, but said the primary law would be the Election Offences Act 1954.

“What is required is simply for our Election Commission to find the courage to implement and prosecute those who flout our Election Offences Act 1954,” he said, having also noted that similar laws exist in Singapore and Australia.

Nizam highlighted the Election Offences Act’s Section 8 covering the offence of “treating”, which he said was widely drafted and makes it an offence to “directly or indirectly provide ‘provision’ to any person for the purposes of corruptly influencing a person’s vote”.

Section 8 also covers the corrupt giving of food, drink “before, during or after an election”.

He also highlighted Section 10, which deems a person to be guilty of bribery “if he promises money, employment, gift, loan etc: a. to procure the election of any person; or b. the vote of any elector or voter at any election”.

“Consequently, would making announcements of goodies, allocations or promising to write-off debts either before, during or after an election be flouting Section 8 and/or Section 10 of the Act? To my mind, it would seem so,” he said.

But he also noted that in a court case in India (S. Subramaniam Balaji vs Government of Tamil Nadu) where the complaint was that promises of goodies amount to a crime, the Indian Supreme Court had ruled that goodies in an election manifesto do not constitute corrupt practice.

Nizam said however that the Indian Supreme Court’s judgment may have been due to the specific laws in that case.

“I think any fair-minded person would find it objectionable, if not utterly reprehensible, that freebies or goodies can legitimately be used for vote-buying.”

Last August, the Indian Supreme Court was reported saying it would revisit its 2013 judgment in that case, which involved pre-election promises to distribute televisions to poor households and questions on whether this was corrupt practices and bribery.

“As for whether an unpassed Budget 2023 can be used as an election manifesto, to my mind, so long as the subject matter does not contravene the Election Offences Act 1954, parties are free to put forward what they believe is beneficial to the voting public,” Nizam said.