KUALA LUMPUR, July 21 — While the informal #benderaputih movement to help to the sections of the country most in need of assistance was lauded by many, some responded cynically and disparaged the humanitarian campaign.

These people derided the movement where desperate households were asked to raise a white flag to signal a call for help as yet another way for those they viewed as lazy to get yet another handout.

On Twitter and Facebook, where the campaign was given life, its detractors conjured images of families with cars, cable TV subscriptions and air conditioning putting out white flags.

The point was simple, according to them: if households can afford all that, then they mustn’t be poor. Just spoiled.

This shaming of struggling households that seek help to cope with the fallout wrought by Covid-19 is rooted in entrenched prejudices about the poor that experts have long debunked, policy analysts said.

One of the most common among the long list of stigmas attached to the poor is that their situation is of their own doing, and the result of perceived laziness and lack of initiative.

Yet there are ample studies that show exactly the opposite, with all pointing to a common finding that indicates poorer people statistically work harder jobs and often for longer hours than those in higher income categories.

“Many people assume if you work hard, you will never be poor, but that is of course false,” said Calvin Cheng, a senior analyst in the Economics, Trade and Regional Integration division of think tank ISIS Malaysia.

“We know that poor people if anything work harder and longer — often in lower-wage, informal, volatile jobs with little protections afforded to them.”

Informal workers are among the worst hit by the pandemic. The majority of them provide labour in services that require physical presence and are paid on a daily or weekly basis.

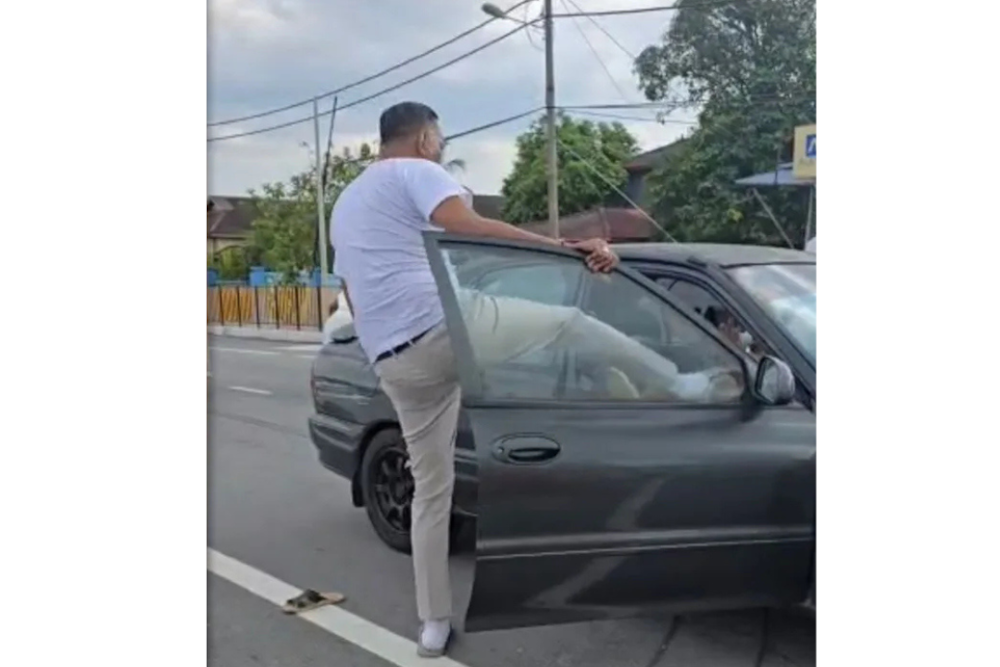

Based on news reports, most of the households that had raised a white flag were those of informal workers left jobless by the prolonged movement restrictions that had forced many businesses to stop operating.

Analysts said this fact explains why many of them, otherwise employed and earning salaries if not for the Covid-19 crisis, are seen in homes with cars or satellite dishes for paid TV subscriptions, which critics took as indicators of financial well-being.

This, combined with common views that the poor live in destitute conditions, has shaped the prejudice that households with certain incomes and material possessions should not qualify for aid, or have the privilege to “demand” and instead accept whatever help they have been given.

Poverty is not the fault of the poor

Muhammed Abdul Khalid, a former economic adviser to then-prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad during the Pakatan Harapan years, suggested that those who think poor people are lazy tend to perceive poverty as a personal failure, a flawed misconception that would give rise to reductive and essentialist views about the poor, such as having natural character defects.

“It’s likely grounded in the stereotype that they’re just lazy, that it’s their own fault that they’re in poverty. So when you put yourself there, you have no right to be choosy,” he explained.

This view would also form the basis of a common stereotype that low-income households tend to be bad at managing their own finances and therefore cannot be trusted to know what is best for themselves, so the responsibility should be shifted to whoever is giving aid.

“There is this notion that they don’t know how to manage their finances, thus better to give them a basket of food so they won’t mismanage. The same with any other aid, they should just take it and don’t choose,” he said.

“Of course studies suggest nothing could be more erroneous than that. Instead, findings show they manage their finances well and we can see this in how they ration what little cash they have for two main expenses — food, and their children’s education.”

Cheng agrees with this but added that the stereotypes are often derived from a limited understanding about modern poverty as a by-product of systemic and structural defects.

“People tend to overstate the agency of people who are poor, and disregard the wider, far-reaching structural, systemic and societal/environmental factors of poverty — issues like systemic discrimination or marginalization/structural inequalities,” he said.

When aid is politicised

But in a country where welfare is highly politicised and prone to leakages, not all suspicions around aid distribution are grounded in prejudice.

Policy makers have long grappled with problems around intervention, which can be susceptible to “exclusion and inclusion errors” that have resulted in people falling through the cracks and leakages that result in aid benefiting the well-off.

“People who are concerned about ‘inclusion errors’, programme leakages to non-needy people… this is a reasonable position to take and there is some room for discussion here. There are often trade-offs between reducing targeting inclusion errors and reducing exclusion errors,” said Cheng.

“For instance, imposing strict requirements on who can receive aid will reduce inclusion errors, but will often increase exclusion errors (needy/poor people may find it harder to meet those strict requirements),” he added.

“Likewise, a true universal aid approach will reduce exclusion errors but will have a high degree of inclusion errors.”

In the Klang Valley, the lockdowns have had devastating economic consequences. Unemployment has soared to levels last seen since the Asian Financial Crisis, as small and micro businesses are forced to shutter by the prolonged movement curbs.

Tricia Yeoh, chief executive of think tank Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), said the unprecedented scale of the health and economic crisis calls for less stringent qualifying criteria for those who need aid.

“Urban poverty is on the rise, and we have to accept the realities that any economic solution must address even middle-class families, whose livelihoods would have been invariably affected by the prolonged pandemic and poorly-managed lockdowns,” she said.