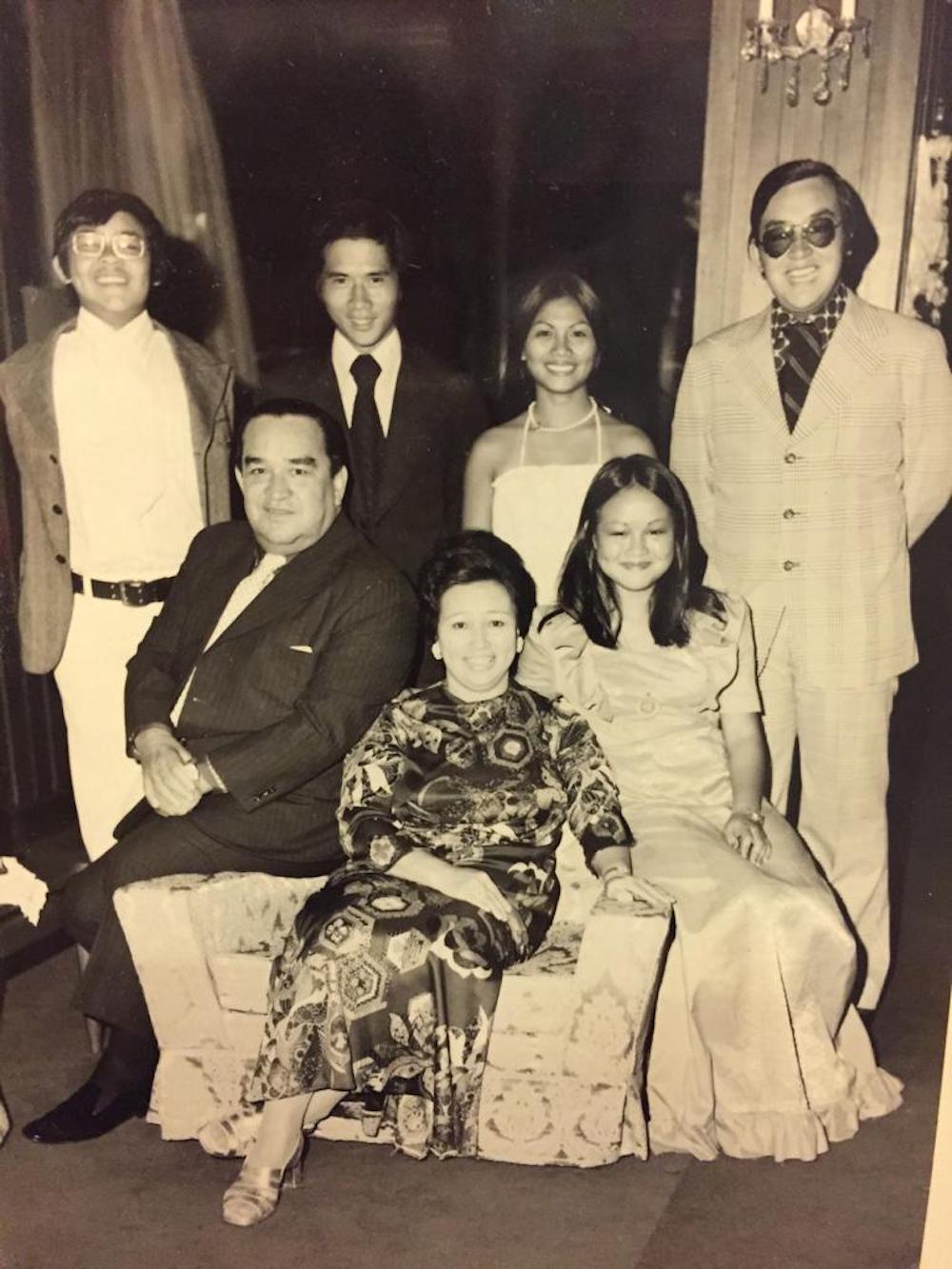

KOTA KINABALU, Sept 16 — Asgari and Faridah Stephens were only toddlers when the new country called Malaysia was declared on September 16, 1963.

The siblings obviously did not know it then but their father, Tun Fuad Stephens was instrumental in negotiating Sabah’s role in the formation of Malaysia back then and would become one of its most talked about politicians in history, as the Bapa Malaysia Dari Sabah (Father of Malaysia From Sabah).

Fuad died in a plane crash on June 6, 1976. Four decades later, the Stephens name still carries weight in Sabah, particularly among the Kadazandusun community where Fuad was the first huguon siou or paramount leader of the Kadazandusun, a revered title that is bestowed with great care.

Out of the political limelight now, the Stephens do not mark Malaysia Day with any particular fanfare, but September 16 is a date that always brings their father foremost to mind as it is just two days after Fuad’s birthday. He would be 98 if he were alive today.

His widow Toh Puan Rahimah Stephens commemorates the poignant day that was her late husband’s biggest legacy, in her own way.

“My mum puts Sabah and Malaysia flags up. She’s very old school like that. Got to love her for it,” said Faridah, 56, and the youngest of the five siblings in the Stephens family.

“But to me, patriotism shouldn’t be a once a year thing. It’s about constantly measuring our country’s performance against documents like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and what we’re doing towards sustainable development goals. It’s about scrutinising leadership. And are we all treated fairly and equally under the law. It’s about small voices being heard too,” she said in a written interview with Malay Mail.

What Malaysia Day means

Like so many Sabahans, Faridah sees Malaysia Day as the country’s real birthdate and hopes that other Malaysians will start to realise its significance.

“It’s the day Sabah, Sarawak, Singapore and Malaya came together to form Malaysia. Some people still say we joined Malaysia but that’s not right. We formed it together. There was no Malaysia before that date,” she said.

Despite being only teenagers when their father died in a controversial plane crash that also killed their brother and other prominent state leaders, Faridah and Asgari still have fond memories of Fuad, both as a family man and a leader for all.

“Most people remember him in the history books as a founder of Malaysia. I was too young at that time to understand what was going on. I remember him as the jovial man who loved his people and wanted everyone to progress,” said Faridah, who was only 14 when her father died.

“He was also a loving dad who believed in education and eating dinner together to talk about everything from sports to schoolwork to world politics. He was a great public speaker and spoke many languages — English, Chinese, Malay, Kadazan, Bajau. He had great friends from all communities.”

The eldest surviving sibling, and the second son born to Fuad — the eldest, Johari died in the plane crash along with Fuad while Affendi died of a heart attack some nine years ago — Asgari remembers their father as an ambitious but down-to-earth leader who never forgot his roots.

“Though he only went to school till Form Five, he was hungry for knowledge. He insisted we all got a university education — it was not an option. He could also connect with anyone — from the simple kampung folk to prime ministers — with ease.

“I remember him as being a great leader. In the ‘50s he had a regular Saturday clinic where he helped kampong folk with legal issues and wrote official letters for them. He was very jolly and and social — we would have dinner together most of the time when younger but as we got older he went out almost every evening to functions,” Asgari, now 58 said.

“However, he was poor with money — he gave or lent lots of money to his friends,” added the businessman.

Fuad’s vision for Sabah

In describing their father’s vision, Asgari and Faridah said he was most focused on education and believed in multiracial and multireligious unity — all were equal to Fuad regardless of race or religion — and his party, Berjaya, testified to that.

“But although he had a native party he worked with all of the races as the focus was independence. He used to write or translate the English speeches for all the other racial parties even,” said Asgari.

“That’s the country we should aim for — where we are all colour and religion blind — while we strive to eradicate poverty in our state, to bring quality education, good roads, electricity and infrastructure to every corner of our state,” added Faridah.

Asgari also said that their father, who embraced Islam at age 50, did not fuss about religion — “he thought that it was a personal thing.”

Born Donald Stephens, Fuad adopted the name Muhammad Fuad when he converted in 1971 but refused to renounce his surname despite being encouraged to.

The unfulfilled dream

Asgari imagines that if his father were alive today, he would have been disappointed that Sabah is still far from the ideal he had fought so hard for.

“It’s not as multiracial as he would have imagined or liked, not as integrated, not as forgiving of other races…The education system would have disappointed him. The level of poverty today after so many years in Malaysia would have appalled him. Corruption would have appalled him.

“The position of the Kadazans and the inability of the leaders to come together would have shocked him. The weakness of the institutions would have worried him,” said Asgari.

The country that Fuad had co-founded, and the vision he passed down to his children, was one that was colour and religion blind, educated and civilised with basic necessities and infrastructure in every corner to serve the people has not been realised.

“There’s this excuse that we’re a large land mass and have difficult to reach areas with a scattered population. Yet they use our oil revenues to build infrastructure in West Malaysia. Is that fair to us?” Faridah asked.

Asgari said that while Sabah has made great strides along the way, there is still a long way to go reach an equal status of progress.

“Progress happens slowly so we don’t realise how far we have come. But still half of the people living in poverty in Malaysia reside in Sabah,” he said.

He also pointed out that special attention is needed on racial integration.

“It’s become like peninsula — much more racial politics as parties fight for power,” he said.

Faridah said Singapore’s exit from Malaysia upset the racial balance of the country.

“The edging out of Stephen Kalong Ningkan in Sarawak and my father in Sabah in favour of Muslim leaders who, in the case of Sabah anyway, embarked on a programme of mass religious conversions, made the intentions of Malaya clear.

“It also showed that leaders who stood up for these states’ rights could be dispensed with. Since then we’ve been dominated by Malaya,” she said.

The sentiment is one that has long existed in Sabah. Local leaders negotiated a 20 point agreement that gave Sabah jurisdiction over certain matters including its customs, land rights, official language and religion, education and immigration, many which have been muddied over the years.

Other long standing issues that continue to rankle include the unequal development between Borneo Malaysia and the peninsula, higher oil royalty payments, a 40 per cent return on income generated by the state and the complex illegal immigrant situation.

The anti-Malaya sentiment resurfaced a few years ago with certain groups of people calling for secession, but it eventually subsided. However, local political parties have been more vocal in fighting for the restoration of their rights from the central government.

Being optimistic again

Faridah is among the Sabahans who feels positive about the “New Malaysia” following the May 9 polls, saying there appears to have been a change in West Malaysia’s attitude to Sabah.

“There is reason to be optimistic again about values in Malaysia becoming more universal and for the greater good of all in our country. We’re seeing Sabah leaders in greater positions of responsibility. May they do us proud by leading well and true,” she said.

She pointed to the long standing issues which have been plaguing the political landscape for so long. Oil revenue for one — something that was greatly harped on about in the current government’s election manifesto.

“And education — more should be done to improve the standard of English and teaching overall. English was meant to be the medium in Sabah but that got forgotten along the way too.

“Will Sabah ever be equal to Malaya? It’s left to be seen,” she said.