KUALA LUMPUR, July 23 — National schools in Malaysia are almost “free” but there is a large — and growing — number of parents willing to fork out thousands of ringgit annually to send their kids to international schools.

As of March this year, records show that there are over 60,000 students in the more than 100 international schools in the country. A whopping 60 per cent of these students are Malaysians.

What is more, the cost per annum of just a Year One education is no less than RM20,000 and can even go up to RM40,000.

Although the fee structures differ from school to school, a check by Malay Mail Online showed that, in some schools, the fees for Year One can even exceed RM100,000 per annum!

And this excludes other costs like study tours overseas and extra co-curricular activities.

So why are parents willing to spend such huge sums on their children’s education?

English is the reason why

According to some parent groups, it is simply to ensure that their children are proficient at spoken and written English.

However, Parent Action Group for Education chairman Datin Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim pointed out that only affluent parents with “really deep pockets” can send their children to international schools.

“Rich parents who realise the importance of the language are willing to send their children to international schools because their syllabus is mostly taught in English.

“This is not the case in national schools where English is taught as a subject but not as the medium of teaching,” she told Malay Mail Online.

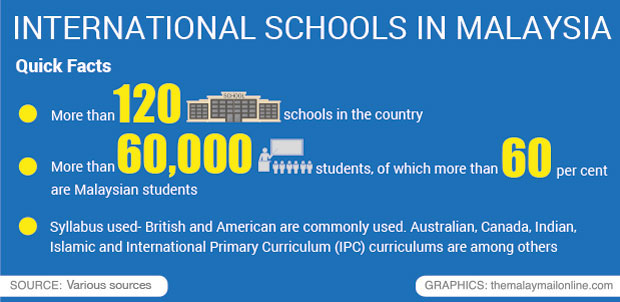

A quick check with some international schools show that most follow the British curriculum where students will be required to sit for the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) programme by the Cambridge International Examinations (CIE).

A quick check with some international schools show that most follow the British curriculum where students will be required to sit for the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) programme by the Cambridge International Examinations (CIE).

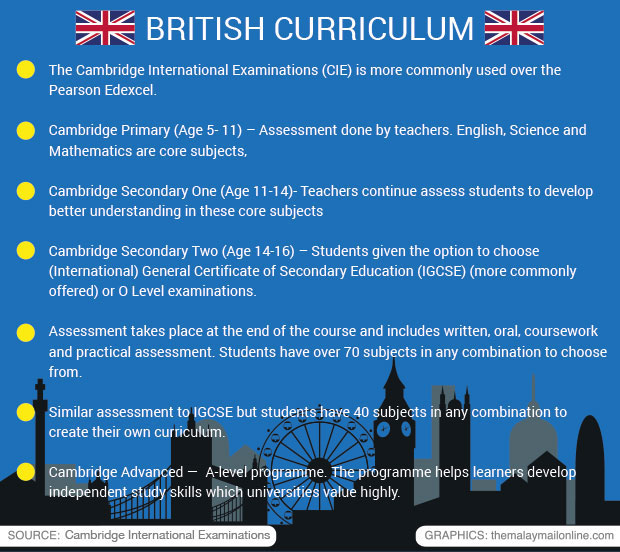

There are also schools that use the American curriculum and the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum which are becoming increasingly popular with a number of schools here.

Other curriculums offered in the country include Australian, Canadian, Indian, Islamic, and the International Primary Curriculum.

Another reason parents opt for international schools, Azimah said, is because of fear that the Malaysian education system would eventually lead to a single stream school where Bahasa Malaysia will become the main medium of teaching.

“This perpetual argument about single stream is turning parents away from national schools too.

“Until all national schools up the ante to improve [the] quality [of education], these [rich] parents will continue to turn away,” she said.

Like Azimah, Melaka Action Group for Parents in Education chairman Mak Chee Kin also said parents were attracted to international schools because of their overall use of English as the medium of instruction.

“It is not surprising that some parents choose international schools over national schools because they are concerned about the marketability of their children, even if that means paying a lot more.

“But ultimately, it is the exposure of English as a medium of instruction in all subjects that attracts parents most,” he said.

Azimah said national schools should not be looked down on, though, just because international schools are thought to produce “elite students.”

Azimah said national schools should not be looked down on, though, just because international schools are thought to produce “elite students.”

“Some national schools have produced top grade students… but the quality of English that is taught as a subject cannot be compared to those at international schools,” she said.

Azimah said there was still room for improvement for English teachers in national schools.

“Perhaps, the ministry [of education] could look into training English teachers because the language is very important for students when they start working,” she said.

A brain drain situation?

Azimah said parents who send their children to international schools want to send them off overseas to study and work.

Because of stringent policies adopted by countries in Europe, she said this makes the transition difficult.

“Strict policies adopted by some countries to curb foreigners from working there will eventually bring back Malaysian children who completed their degrees or Masters programmes,” she said.

“So, I wouldn’t say this phenomenon [of children going to international schools] would cause a brain drain situation or a class divide among international school students and national school students,” she said.

Azimah said international schools also emphasise values and respecting other religions and cultures, just the same as national schools.

When asked if these children would face difficulties getting a job here given that their proficiency in Bahasa Malaysia would be lower — there are instances where they have zero ability to speak or write the national language — she said that would not be the case.

When asked if these children would face difficulties getting a job here given that their proficiency in Bahasa Malaysia would be lower — there are instances where they have zero ability to speak or write the national language — she said that would not be the case.

“In the working environment here, English is still widely used as I know many who went to international schools, studied overseas but returned here to work and they are adjusting well to our culture,” she said.

Other reasons why parents choose international schools

According to a parent who only wanted to be known as Michael, it is the rich variety of co-curricular activities that made him want to send his son to an international school here.

“It is like a one-stop centre as you have music classes and sports activities planned for students after their studies.

“These, you don’t get from national schools but, of course, the more important reason is quality of education which I feel is far better than our local [education] system,” he said.

When asked if he would eventually send his son to study and work overseas, Michael said that was his plan but added that he wasn’t sure of the future.

“We are financially okay at the moment and I would definitely want my boy to study and work overseas but let’s see how things go later on,” he said, adding that political instability in the country was also a reason why he would want his son to work in another country.

What Michael said seems to echo the sentiments of many parents who send their children to international schools.

So, despite what people like Datin Noor Azimah say, it would suggest that a child educated in an international school here — no matter which curriculum the school follows — already has one foot out of this country already.