KUALA LUMPUR, April 14 — For better or worse, Tasek Gelugor MP Datuk Shabudin Yahaya’s recent remarks in Parliament has cast a spotlight on child marriages in Malaysia.

With the country aiming for first world nationhood, should marriages of minors be allowed to continue? There have been arguments for and against this practice, with child development advocates heavily in favour of ending it.

To help you understand this issue better, Malay Mail Online has compiled a list of the facts and figures that you should know:

1. What does the law say?

Malaysians are only considered an adult by law when they turn 18, but the legal age applicable on matters like when they can have sex and get married is a different thing altogether.

The age of consent for sexual intercourse in Malaysia is 16, which makes sex with any woman below age 16 a crime, regardless whether they consented to it or not, and punishable by law. However, marital rape is not a crime in Malaysia.

Children are actually allowed to marry under existing Malaysian laws. The legal age to marry also depends on whether you are Muslim or non-Muslim.

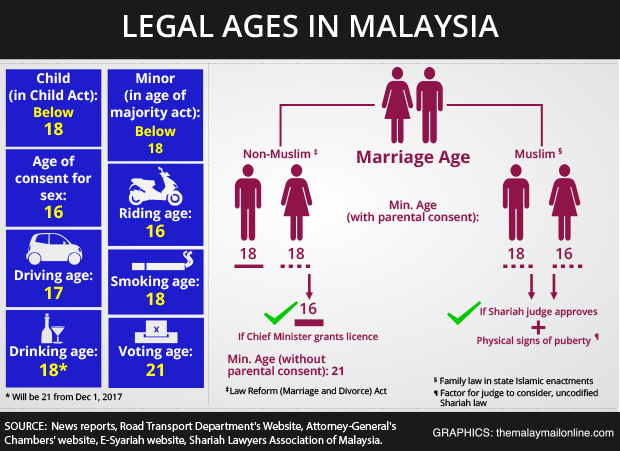

Under the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act's Sections 10 and 12, non-Muslims can only be legally married if they are aged at least 18 and will require parental consent for marriage if they are still below 21. Under this law, they are considered minors if they have yet to turn 21 and are not widows.

But the same law provides for an exception, where a girl aged 16 can be legally married if the state chief minister/ mentri besar or in the case of the federal territories, its minister, authorises it by granting a licence; as are ambassadors, high commissioners and consuls in diplomatic missions abroad.

As for Muslims, the minimum legal age for marriage in the states' Islamic family laws is 18 and 16 for a male and female respectively, but those below these ages can still marry if they get the consent of a Shariah judge.

Local Islamic family laws do not list the factors that Shariah courts need to consider before approving underage marriages or impose a limit on how young a Muslim can be married under this exception.

But Shariah Lawyers Association of Malaysia deputy president Moeis Basri told Malay Mail Online that Shariah courts are bound by Shariah laws regardless of whether they are codified.

In practice, he said this means that Shariah judges will exercise their wide discretionary powers to consider all relevant factors before deciding whether or not to approve underaged marriage. This includes looking at physical signs showing puberty such as menstruation in the girl, and also the level of maturity in both the child bride and groom to be.

“Under the Shariah law, only (a) person that has attained age of puberty can get married. The age of puberty may differ from one person to another. This is one of the things that any application for underage marriage needs to prove. Of course there are other factors that need to be considered by the court before allowing or rejecting the application,” he said, adding that applications for Muslim underage marriages are not automatically approved but have to be shown to have merits.

2. Women marry young

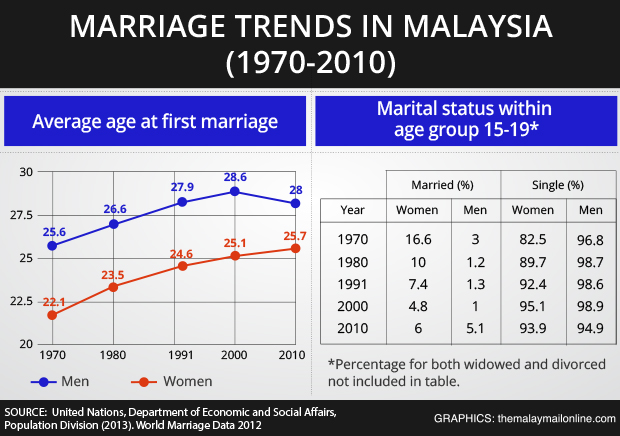

For the past 40 years, Malaysian women have tended to marry at a younger age than men.

Even as the average marriage ages for both genders have been rising from 25.6 and 22.1 in 1970 to 28 and 25.7 in 2010 for men and women respectively, Malaysian children have still been marrying at a young age and in some cases also ending their marriages at an equally young age.

According to the 2000 census, there were 10,267 out of 2,411,581 children aged between 10-14 who were married, while 229 and 75 children in this age group were widowed, divorced or permanently separated. Girls who were married outnumbered boys in this age group at 58 per cent to 42 per cent.

When broken down according to gender, 4,334 out of 1,237,519 boys aged 10-14 were married as of 2000, while 71 were widowed and 17 were divorced or separated. As for the girls, 5,933 out of the 1,174,062 in this age group were married, while 158 and 58 were respectively widowed and divorced or separated.

The 2010 census oddly does not show any figures for those in the 10-14 age group who were married, widowed or divorced. Instead, it records all 2,733,427 children in this age group as falling under the Never Married category.

As the overall population grew from 22,198,276 in 2000 to 28,334,135 in 2010, the number of those married in the 15-19 age group more than doubled from 65,029 to 155,810, while those who were widowed at these ages went up from 594 to 1,451, and those divorced or permanently separated from their spouse by then increasing from 849 to 1,071.

In 2000, those in the 15-19 age group who were married was overwhelmingly female at 53,196 as opposed to male at 11,833. In 2010, it was split between females at 82,382 and males at 73,428.

3. Demand for child marriages

3. Demand for child marriages

The census figures reflect what appears to be sustained demand for child marriages in Malaysia.

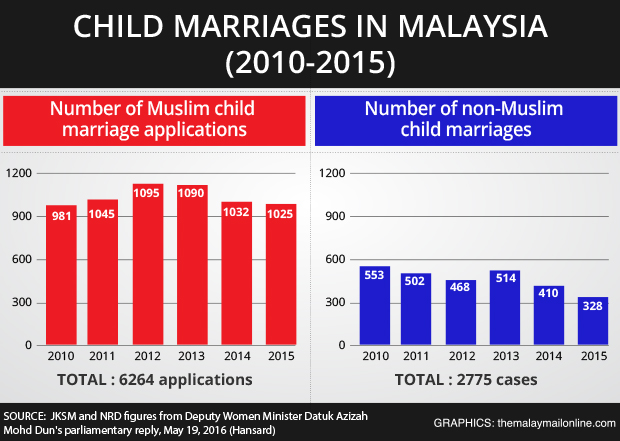

On March 7, 2016, Women, Family and Community Development Minister Datuk Seri Rohani Abdul Karim told Batu Kawan MP Kasthuri Patto in a written parliamentary reply that the number of applications for Muslim child marriages between 2005 to 2015 was 10,240. The figure for the approved applications was not provided.

The annual average of applications for Muslim child marriages recorded by the Department of Shariah Judiciary Malaysia between 2005 to 2010 is 849, while the annual average for 2011 to 2015 is 1,029, Rohani had said.

As for non-Muslim child marriages recorded by the National Registration Department during the 2011 to September 2015 period, there were 2,104 girls aged between 16 and 18 involved, Rohani said.

The majority of these teenage girls (68 per cent) or 1,424 of them were married to men aged 21 and above, while the remaining 32 per cent or 680 of them were married off to those closer to their ages at 18-21.

Amid calls for child marriages to be banned in law in Malaysia, civil society groups have also advocated recently for the inclusion of what they dub a “sweetheart defence”, where young couples with small age gaps, such as teenagers are spared prosecution.

Critics of child marriages have highlighted high-profile cases such as where a 40-year-old man married a 13-year-old girl that he had raped and a man in his 20s marrying a girl he had raped at the age of 14, while others have raised the chain of problems linked to child marriages such as high-risk pregnancies, greater risk of maternal death and domestic violence, as well as disrupted education.