KOTA KINABALU, Oct 14 ― Ranau is well known as the backdrop of the iconic Mount Kinabalu and Malaysia’s first World Heritage Site, but what is not so obvious is that it is also home to a warm, welcoming people described as the epitome of multiculturalism.

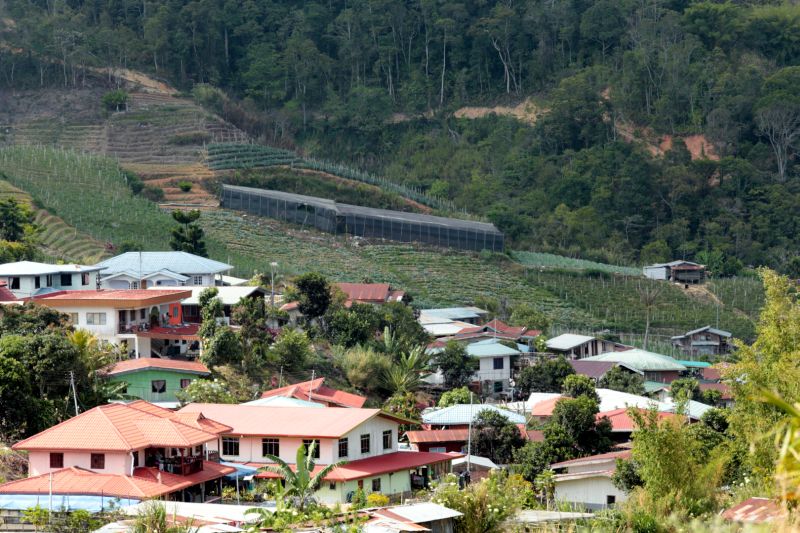

At the foothills of the mountain, the predominantly Dusun community live a simple life centred around farming and family. They respect the land on which they live, and believe that the spirits of their ancestors are ever present and watching over them.

Their days are spent toiling their farms, selling their produce at wooden rickety stalls or to middle men to be taken to the city.

The temperate weather invites long walks along the winding hilly roads where natives often wave at passing motorists and flash friendly smiles.

Their lifestyle has been this way for decades, and even the introduction of new religions in the 1940s and the rapid development in recent times have not changed their laidback, warm disposition.

Sabah Tourism, Culture and Environment Minister Datuk Seri Masidi Manjun recently waxed lyrical about the virtues of his hometown community, claiming it to be among the most tolerant, gentle and accommodating in the country.

“If you want to feel the essence of a multiracial, tolerant and peaceful community, Ranau is one of the best places,” he said, explaining that the people have always accepted other faiths without much fuss.

“People here don’t look at religion as a divider. Their culture takes precedence, and they place this above all else,” said Masidi.

According to the 2,000 population census, Ranau is nearly equal parts Muslim and Christians ― 46.85 per cent of the population in Ranau are Muslims while 45.68 per cent are Christians.

Around 6 per cent were recorded as “others”, presumably referring to traditional ancestral beliefs and traditions, sometimes called paganism. Another 1.09 per cent are Buddhists, 0.06 per cent are Hindus.

Masidi partly attributes this to the fact that both Muslim and Christian missionaries arrived in the district about the same time in the early 20th century.

European and Australian Christian missionaries took the trouble to find out which villages were mainly Muslims converted by Javanese preachers and avoided these, preferring to seek other villages that were still practising paganism.

As a result, Ranau has an irregular religious distribution where Christian and Muslim villages often mix. Most Christian-majority villages will have a Muslim household or two and vice-versa with a Muslim-majority village.

In Ranau town, the Basel church, a Chinese temple and the mosque are located next to each other along the same road, Jalan Masjid.

Last year, a photo of a newly-ordained priest from Kampung Marakau, Ranau, made rounds on social media, but not because it was unusual to have a Ranau-born boy making clergy.

The photo of 35-year-old Father Abel Madisang, the second youngest of 12 childrens from Ranau farmers, gained attention because he had the love of support of family and relatives of all faiths celebrate with him in church ― tudung and all.

Sabahans who commented on the photo were quick to add “this is a normal scenario in Sabah, we don’t see religion as a barrier.”

In Sabah, particularly in the 90,000 strong Ranau community, Abel’s family background is not peculiar; most villagers would have a family member, or relatives of a different religion.

Joseph Seliun, 31, a farmer who lives in Kampung Bundu Tuhan, not far from Kinabalu Park, grew up with 12 siblings and attended church every weekend with the entire family.

His village consists mostly of Christians who started following the faith post-Colonial times when a British priest moved to their village and taught them modern farming techniques.

His grandparents were, like many Dusuns before them, pagans who worshipped the Kadazandusun God, Kinoingan and the spirits around them.

“But we were taught from young how to worship in church. Its part of the family tradition,” he said. So ingrained was their faith that two of his sisters became nuns for their church nearby.

So it was understandable that his father was a little taken aback when one of his daughters told the family she wanted to marry a Muslim man.

But despite the initial shock and doubt, the wedding went ahead and Seliun now has two Muslim siblings, and two sisters who are nuns.

“I was only 11 when my sister told my family she was converting to Islam to get married. so I didn’t think too much of it. I still don’t. I don’t think there is much difference. When she comes home, she still eats with us,” said Seliun, adding that his brother-in-law was also understanding of the differences.

“I don’t think we make any special considerations. When she comes home with her family, it feels mostly the same. She eats from the same dishes. During my wedding, she came to our church with her husband and family,” he said.

Rem Dambul, a Muslim Dusun climatologist currently serving as deputy director in the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation in Putrajaya, hails from Ranau, and has warm memories of his childhood with family members from different religious backgrounds.

“I had my Christian cousins come and live with my family for awhile and they would wake up before dawn along with my family and help my mother prepare sahur for us during Ramadan. They also joined in for buka puasa. No issue,” he said.

The community’s attitude about their religion could be described as nonchalant, as personal a choice as whether you prefer driving a manual or automatic transmission car.

“It is not because we deliberately wanted to avoid talking about it. It is just something natural for us... I think it is just the nature of Sabah people. They don’t like to talk about things that would highlight their differences. Faham sama faham saja bah, orang bilang,” he said, using the colloquial slang that roughly means “it’s an unspoken understanding”.

“We don’t talk about it, we just respect each other’s beliefs. I don’t know what people expect us to do. They’re my family, are we supposed to argue about religion? It doesn’t change who we are or our culture,” said Seliun.

The only drawback for his sister, he says in jest, is that she can no longer partake in sinalau bakas ― smoked wild boar ― a staple here during festive occasions.

Japiril Suhaimin, a Dusun Muslim native to Kundasang, agreed that growing up with other religions was the norm for many families to him, so much so that it was hard to think of any incidences where allowances or special considerations had to be made to suit others.

However, he said that in some of the festivities, the Christian hosts tended to their Muslim guests with smoked payau ― a local deer instead so they do not feel left out.

“It’s not really an issue, whether they serve pork or not. We don’t eat that particular dish if they do but I don’t think we question it. There is a lot of good faith involved on both sides. But Christians here are hospitable and likewise,” he said.

These festive occasions also often see the village dogs wandering around, looking for scraps from compassionate guests, and are often rewarded by the platefuls.

Another example of the religiously ambiguous town is that there are “anjing kampung” ― mongrels who may or may not belong to anyone ― found wandering around the villages and town and many are fed well.

“Many villagers keep dogs, regardless of religion. I have dogs near my house, too. We feed them, and occasionally come into contact with them. We just wash ourselves or samak according to the Quran,” said the 53-year old businessman.

Japiril’s approach to his faith, is what Masidi described as its own brand of Islam, evolving from the gentle Dusun culture, and being introduced to the religion by a non traditional Muslim estate supervisor from Java, Indonesia.

“The fact that the Dusuns of Ranau learned of Islam through a Muslim traditional healer who was not a preacher by profession, means we grew differently from other Muslims. I believe it makes us more gentle, peaceful, and tolerant,” he said.

Masidi also said that both Islam and Christianity grew in tandem in the region, gradually phasing out paganism, but at the same time, created a harmonious bond among the people.

Japiril, who travels to the state capital some two hours away, lives in Kampung Kundasang, has a lot of ties to Christianity. His mother’s family is Christian and he married a Christian Dusun who converted to Islam when they got married.

“She used to celebrate Christmas, and me, Hari Raya. Now, we celebrate both,” he said.

“I still go to Friday prayers religiously, but also I’d go to a church for weddings and funerals. I don’t see what's the harm in it. It’s not like we Muslims will be tempted to sway just because we enter a church. It is not about us, but about celebrating the occasion,” he said.

“It’s unthinkable for us to let our religion get in the way of family or good relationships.”