KUALA LUMPUR, Aug 9 — Eight years ago Pastor Henry Martinus found a four-year-old child deserted at his doorstep.

He took her in, naming her Abigail. He thinks she may be of Indian descent but cannot tell for sure because Abigail, who has Down’s syndrome, came with no documents.

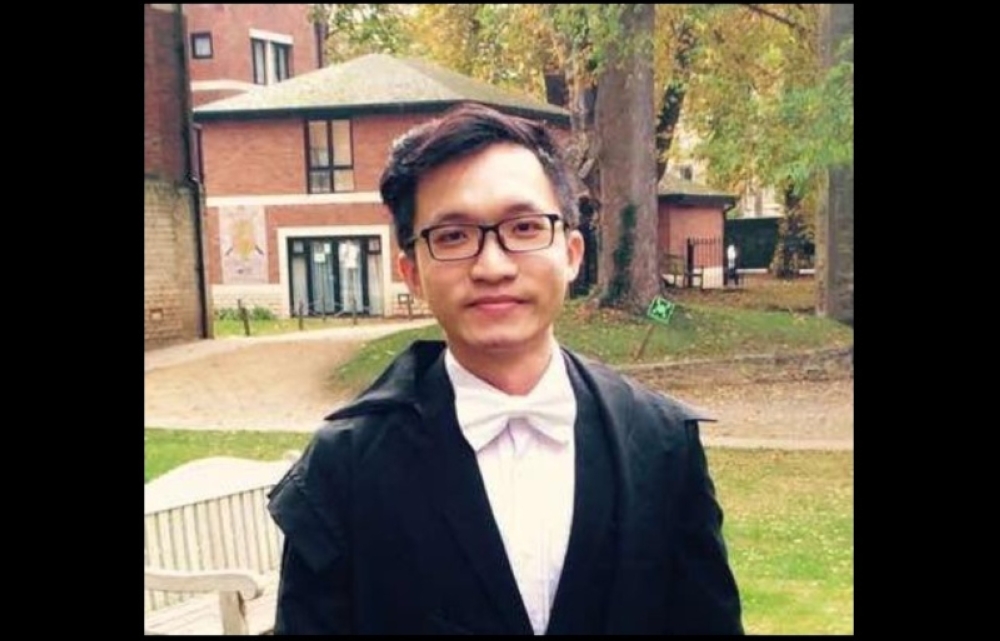

Martinus and his wife Serena Wong have come to care for two more undocumented children, Isaac, 5, and Isabella, 4, abandoned at birth by Burmese migrant worker mothers who have long disappeared.

In the eyes of Malaysian law Abigail, Isaac and Isabella are stateless, the task of getting them legally recognised is daunting and impeded by opaque rules even when they have willing sponsors.

Two years ago, Martinus and his wife applied for Malaysian citizenship for the three children they love as their own, planning to legally adopt them after citizenship had been granted.

But their plans are on hold. In June, the couple received a letter from the Home Ministry rejecting the children’s application for citizenship without stating any reason.

“They (the children) don’t belong here, or anywhere else… without the documentation they have no legal identity and by extension, no nationality,” Martinus told Malay Mail Online.

Difficult process

“Just before the general election we managed to get them their birth certificates when there was issue of stateless Indians and soon after we put in the citizenship application with the assistance of the staff from the Home Ministry.

“We understand the difficulty… we could be traffickers or smugglers but we figured they (the authorities) would check for references or at least interview us about the children and inquire on our background before rejecting our application,” he related.

Malaysian nationality would make the life easier, especially for Isaac, who suffers from rare birth defects that affect multiple parts of his body systems known as VACTERL Association, it means access to subsidised government healthcare.

Four-year-old Alaani Elsie, who was adopted by public relations executive Kim Thiruchelvam, was also denied a Malaysian citizenship during the same period as Abigail, Isaac and Isabella.

“Both of us, her legal parents, are Malaysians. How does it make sense that the child we adopted through the government welfare system is rejected citizenship?”

Kim and her husband Belden Premaraj, 47 adopted Alaani, as a six-month-old baby abandoned by her Burmese-Arakanese refugee mother at the Kuantan Hospital four years ago and filed for citizenship two years ago.

The couple had put the word out they were looking to adoption in 2010.

When they got word of the baby, Kim drove to the government shelter in Kuantan at the next opportunity but prematurely-born Alaani was hospitalised for chronic pneumonia and shared a cradle with two other babies.

The 44-year-old filed the paperwork required to get the child out of the welfare system and submitted the application to foster the child.

In the meantime, the child had been admitted to a government hospital as a foreigner. The bill for her disposable diapers and treatment came to RM3,000, which Kim paid.

Putting a figure on Malaysia’s stateless children

Estimates of just how many stateless children live in Malaysia are hard to come by.

A parliamentary written reply from Home Ministry dated March 11, 2009, said that there are 32,440 stateless children in the country but National Registration Department (NRD), an agency under the ministry, has since said it does not keep records of stateless persons.

More recently, Malaysia’s Women, Family and Community Development Ministry told Malay Mail Online there are 95 stateless children under the care of centres registered with the state’s Social Welfare Department.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates there are about 12 million of stateless persons around the globe, with as many as 125,375 in Malaysia of which 40 per cent are children.

They are largely from the migrant community with over 90 percent from Myanmar and a sizeable number from Sri Lanka, Somalia, Iraq, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan. Others are from nomadic indigenous tribes living in remote jungles of the peninsular or from seafaring communities in East Malaysia and the remainder are abandoned babies, orphans and minority ethnic groups.

The United States Department of State in its report on human rights in Malaysia last year noted that the Malaysian authorities considered children born out of wedlock to foreign women to have inherited their mother’s citizenship, which poses complications when the foreign mother is unable to show valid proof of citizenship.

This is being challenged by in court by 16-year-old Navin Moorthy, after his citizenship was revoked and subsequent applications were denied by the NRD although he was born to a Malaysian father and Filipino mother.

Legal Limbo

Malaysia has not ratified the UN conventions relating to statelessness, but it is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) since 1995, albeit with some reservations to Article 7 of the CRC, which specifies the country’s obligation in legally recognising undocumented children.

While the Article 15 of the Federal Constitution stipulates that a child born in Malaysia can only be granted the Malaysian nationality if one of the parent is a citizen or permanent resident in this country at the time of birth, citizenship is not acquired automatically and the parents are required to register the child born, stated the National Registration Department previously.

Deprived of access to basic education and healthcare, many struggle to make a living as grown ups without the legal bond and are driven to the fringes of society, related Lawyers for Liberty executive director Eric Paulsen, who has worked on a number of cases pertaining to statelessness.

“We understand the government’s concerns but these are not people asking for naturalisation… these are helpless children whose lives are in a limbo,” he said.

The Social Welfare Department, in an emailed response, also noted the eventual problems arising from the complications faced by the children pointing out that the “situation may lead to increase in social ills”.

While the department is committed to assist families contemplating adoption, including mitigating the red tape faced when the applications for birth certification and citizenship are brought to NRD’s attention, the process is without clear guidelines.

“I was not told nor was it written anywhere that I need a police report to obtain Alaani’s birth certificate… the NRD had this event to give adoptive parents the birth certificates, to which we were invited, but Alaani wasn’t given hers because I did not file a police report stating that we had adopted her,” said Kim, whose frustration led her to write an open letter to Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak when she found out Alaani’s application was denied.

The rejection letters too, were vague. Home Ministry’s registry and association division’s chief secretary Azizi Wahab regretfully informed Kim and Martinus their applications were “unsuccessful” and that they can reapply.

“We want to re-apply or appeal, whatever they call it, but how? When we don’t know why the citizenship applications were denied in the first place. Which criteria was not fulfilled?” posed Martinus.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) noted that MyDaftar, a campaign to address rampant statelessness among the country’s ethnic minorities prior to Election 2013, has been effective in combating problem but added that the scope of the efforts must be expanded.

“Stateless children, through no fault of their own, inherit circumstances that limit their potential: They are born, live and, unless they can resolve their situation, die as almost invisible people,” said the body, in a statement to Malay Mail Online.

Not only does statelessness exacerbate a child’s vulnerability to abuse and exploitation, it also denies a child the right to education, added Unicef.

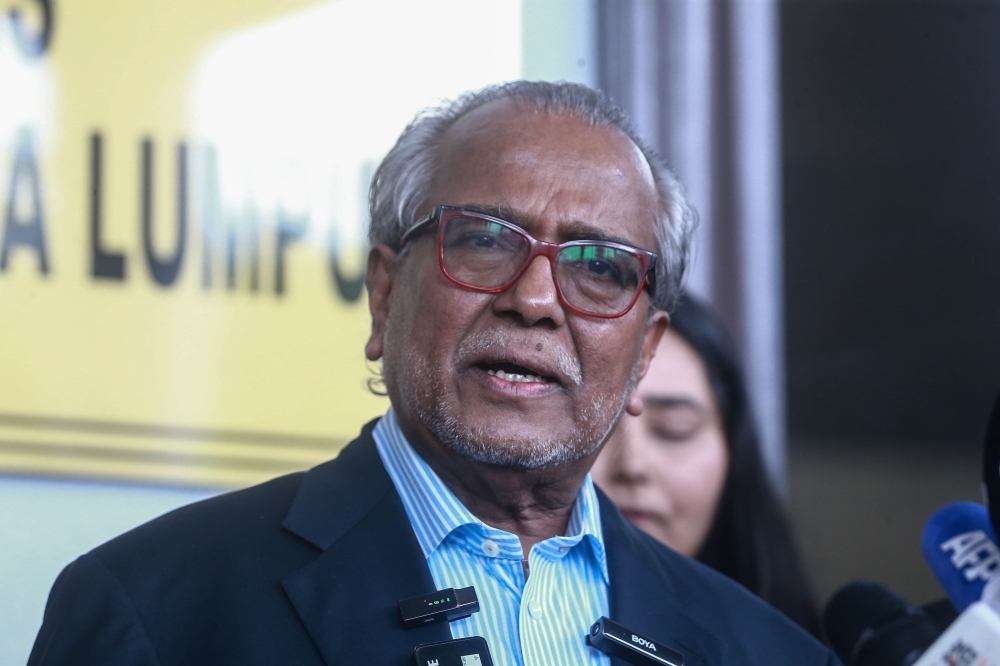

Special Implementation Task Force on the Indian Community (SITF) chief coordinator Datuk N Sivasubramaniam, who in charge of the MyDaftar, prompted the government look into exemptions for children born into such circumstances.

“We cannot continue to deny the fact in a developing country you will have abandonment of children, all developing nation face this issue,” Sivasubramaniam said in an interview. He added that the NRD through SIFT had received 9,529 applications for identification certifcates of which 4,023 were for citizenship, of which 6,590 have been resolved.

The Home Ministry reiterated the complexity of the laws to Al Jazeera stressing that adoption does not entitle one to “automatic citizenship rights”.

“Ideally, it is the responsibility of the birth mother and father to obtain citizenship by dealing with their country’s representative to avoid their child from being stateless in Malaysia.

“This is also to ensure Malaysia is not given the undue responsibility and burden of citizenship issues of foreign nationals who intentionally refuse to deal with their child’s identification documents from their country of origin,” said the ministry, in a statement to the international news agency.

For Martinus, though, the statement brings cold comfort.