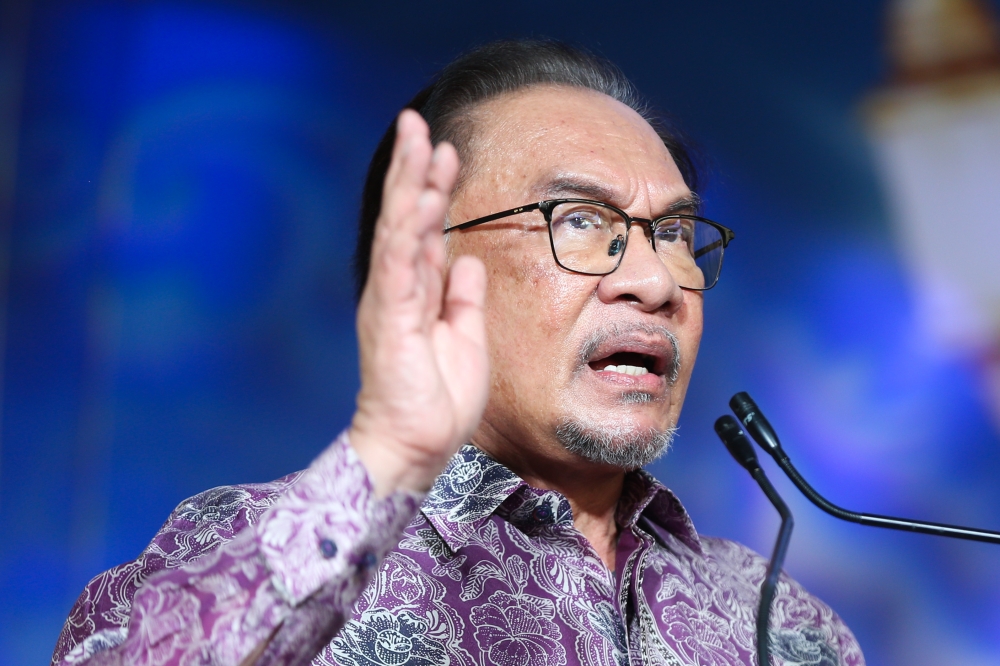

JANUARY 27 — When Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim acknowledged that public fund losses over the last two years likely exceeded RM15.5 billion, the statement landed with a thud precisely because it was delivered without drama.

There was no no sheer bombast and outrage by the people.

For that matter by Anwar himself. Literally the only leader to have been incarcerated before being released.

Only to see him beating all odds to be elected the 10th Prime Minister of Malaysia on November 24th 2022. Hence the moniker PMX. With X being the Roman numeral to define him as the tenth Prime Minister of Malaysia.

For the lack of a better word, the first Prime Minister would go against all forms of corruption while obliged to do so with a Coalition.

Speaking of the temerity of “Malaysia Boleh,” (Malaysia Can) this must be one of the highest orders of one man one vote, only to put all things to one man: Anwar.

Thus when Malaysia cannot get its fair share of reforms over the last few years, the voters themselves must understand that they did not give Anwar a government with the fullest mandate. Anwar has to cobble together a Coalition with a 2/3 majority.

Not only did Anwar manage to hit the mark within the first few months of the Unity Government but he waited patiently to strengthen the grand Coalition to start the process of attacking public corruption without undermining his own government, which risks an immediate meltdown, if parties stitched together to form his “Madani” (Civilizational) government could not withstand the acid test of chipping away at the forces of corruption, including those in the upper echelon of the military brass. In another country in Southeast Asia, what Anwar did, without a shadow of a doubt, could have brought about a Coup against him and the whole of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and the Prime Minister’s Department (PMD).

From a position of relative electoral strength — since many in the academia even opposition remain derisive of his outstanding services — Anwar’s cynicism that the problem of the problem is much deeper than meets the eyes came as a sober admission. Why ?

Invariably, what has been detected, recovered, or prevented over the last two years alone is probably only a fraction of what has been lost.

To be sure, there have been research institutions even the World Bank that have attributed the losses of the Malaysian government to go into RM 3 Trillion or more. With the United Nations (UN) once suggesting in 2018 that Malaysia’s level of corruption was only second to China.

This is astounding since China is the most populous country after India. While Malaysia only has a population of 35 Million people.

In other words, RM15.5 billion is not the mountain—it is the visible ridge above water.

Either way, the figure itself deserves careful unpacking.

RM15.5 billion refers to monies that enforcement agencies have either clawed back or stopped from leaking further through fraud, corruption, inflated procurement, and regulatory arbitrage. It does not represent the full value of public theft.

If anything, it is a conservative baseline—an accounting of what investigators have managed to catch.

By definition, the larger share of illicit flows remains hidden, misclassified, laundered, or buried within layers of contracts and intermediaries that never attract attention.

This is why the phrase “tip of the iceberg” is not rhetorical excess but analytical precision.

Public theft rarely announces itself. It thrives in opacity, procedural complexity, and the grey zones between policy intent and bureaucratic execution.

Leakages are embedded in procurement chains, in rent-seeking concessions,

in monopolistic licenses, and in quietly manipulated specifications that favour the same vendors again and again.

What is exposed is usually what goes wrong within the scheme, not the scheme itself.

Malaysia knows this problem well. From procurement overruns to cartelised supply contracts, from customs leakages to subsidy arbitrage, the country has wrestled with structural vulnerabilities for decades.

The difference today is that the scale is being openly acknowledged at the highest level of government. That candour matters.

It signals an understanding that corruption is not episodic misconduct by a few bad actors, but a systemic drain on state capacity and public trust.

The economic cost is immediate and measurable. RM15.5 billion could have funded hospitals, schools, flood mitigation, digital infrastructure, or meaningful wage reform for civil servants. Instead, these resources were diverted into private hands, often recycled into speculative assets, overseas accounts, or political patronage networks.

Every ringgit lost is a ringgit that must be replaced through higher taxes, reduced services, or additional borrowing—burdens that fall squarely on ordinary Malaysians.

Yet the deeper damage is political.

hen citizens hear that billions can disappear in just two years, cynicism hardens. Trust erodes not only in politicians, but in institutions themselves.

The danger is not merely anger, but resignation—the belief that theft is inevitable, reform cosmetic, and accountability selective. Once this mindset takes root, it becomes corrosive.

Dlemocracies do not collapse only through coups or authoritarianism; they also decay through apathy born of repeated betrayal.

This is why comparisons with the 1MDB era are unavoidable.

That scandal taught Malaysians a painful lesson: grand narratives of development and national ambition can be weaponised to justify extraordinary levels of secrecy.

The aftermath also revealed another truth—recovering stolen assets is far harder than preventing their loss in the first place.

Years of litigation, international cooperation, and diplomatic effort yielded only partial restitution. Prevention, therefore, is not merely cheaper; it is morally imperative.

To the government’s credit, enforcement actions have intensified.

Freezing accounts, seizing assets, and tightening oversight send a clear signal that impunity is no longer guaranteed.

But enforcement alone cannot dismantle entrenched incentives.

Public theft is sustained by predictable patterns: concentrated discretionary power, weak procurement transparency, revolving doors between regulators and regulated entities, and a culture that treats public resources as spoils rather than trust.

Real reform must therefore be structural.

Procurement systems need radical transparency—not just published tenders, but open-data tracking of contract variations, subcontracts, and ultimate beneficiaries. Regulatory agencies must be insulated from political interference, with professionalised leadership and independent audit trails.

Whistle-blower protections must be credible, not symbolic, ensuring that those who expose wrongdoing are shielded rather than punished.

Above all, political financing must be addressed honestly, because illicit money does not vanish; it circulates, often back into the political system itself.

There is also a regional and international dimension. In an era of cross-border finance, stolen public funds rarely stay put.

They move through offshore jurisdictions, shell companies, and compliant banks.

Malaysia’s fight against public theft therefore intersects with global governance norms on transparency, beneficial ownership, and anti-money laundering. Cooperation is not optional—it is the battlefield itself.

Ultimately, the Prime Minister’s admission should not be read as an indictment of the present alone, but as a challenge to the future.

A country that normalises billion-ringgit leakages cannot credibly aspire to high-income status, digital leadership, or moral authority in regional affairs.

Development is not only about growth rates; it is about integrity in how wealth is created, distributed, and safeguarded.

RM15.5 billion is already a staggering number.

But its real significance lies in what it implies—that much more remains unseen.

The iceberg is vast, and only sustained political will can melt it down to size.

Malaysians deserve more than periodic revelations; they deserve a system where such losses become unthinkable rather than routine.

Until then, every recovered ringgit will stand as both a victory and a reminder of how much is still missing.

* Phar Kim Beng is professor of Asean Studies and director of the Institute of International and Asean Studies, International Islamic University of Malaysia.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.