MARCH 29 — Malaysia has acceded to the Rome Statute, which means that Malaysian citizens are now subject to the International Criminal Court (ICC) if they commit atrocities like genocide, systematic crimes against a certain population, war crimes, or if they wage war.

The sultan of Johor spoke out strongly against Malaysia’s accession to the Rome Statute, claiming that it contradicted the Federal Constitution because it affected the powers of the rulers.

A few lawyers have dealt with the issue of Malaysia’s royal immunity under the ICC that expressly removes immunities for heads of state or government.

Lawyer Lim Wei Jiet points out that even though the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong is, in name, the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, it is really the prime minister who decides on any military action because the king is obliged to follow the PM’s advice.

Lawyer Shad Saleem Faruqi also said previously that it is the government, not the king or the rulers, who will be sued if court proceedings relate to royals’ actions that are made in their official capacities.

However, even though the ICC has nothing to do with the Agong, this does not mean that Malaysia should go ahead and ratify the Rome Statute.

The main concern is Malaysian sovereignty. I do not think that Malaysian nationals, including the prime minister, should be subject to a foreign court, even if the ICC is dubbed the “court of last resort.”

United States national security adviser John Bolton reportedly said last September that the ICC threatened American sovereignty and US national security interests, in response to reports that the world’s top criminal tribunal could probe possible crimes by US military personnel in Afghanistan since 2003.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo then said earlier this month that the US would deny visas to ICC personnel attempting to investigate Americans.

ICC prosecutors — who are also seeking to investigate war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Afghan national security forces, Taliban and Haqqani network fighters — reportedly disclosed information that US military and intelligence agencies tortured detainees in Afghanistan and in other “black sites.”

The US and Russia have rejected the Rome Statute, of which 123 countries including Malaysia are party to, while other major powers like China and India — which are reportedly critical of the ICC — have not signed it.

How does being party to the ICC help Malaysia? As idealistic as it is to desire world peace and justice, Malaysia is better off looking inward and focusing on domestic reforms so that the nation can reach its fullest potential.

Any war crimes or “crimes against humanity” (widespread attacks like murder, rape, enforced disappearance of persons, or apartheid against any civilian population) committed by Malaysian nationals should be dealt with in the Malaysian justice system.

Malaysian citizens accused of international crimes should be tried under Malaysian law by Malaysian prosecutors and face Malaysian judges, with protection under the Malaysian Federal Constitution. If there are no local laws yet against war crimes or crimes against humanity, then we can enact those.

Why should we submit fellow Malaysians — be it the prime minister, military personnel, or police officers — to a Europe-centric court? Upholding United Nations human rights treaties is fine, but allowing a foreign court to convict and imprison a Malaysian citizen is unacceptable.

Malaysian nationals who commit international crimes should also suffer in Malaysian jail, rather than experience European standard detention in the Hague with a tennis court, gym with instructors, and satellite TV with international channels.

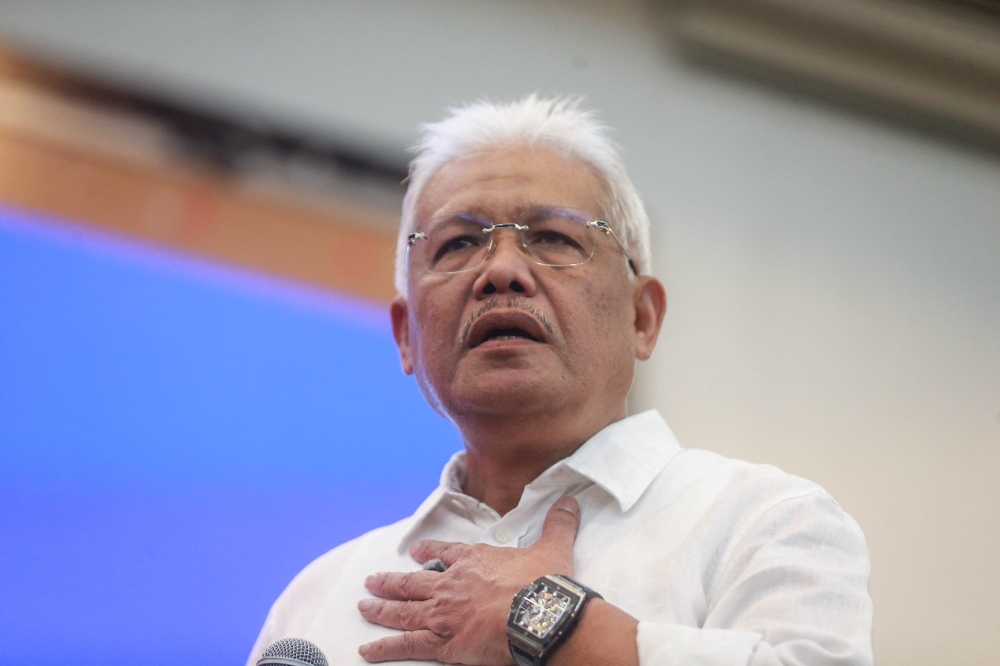

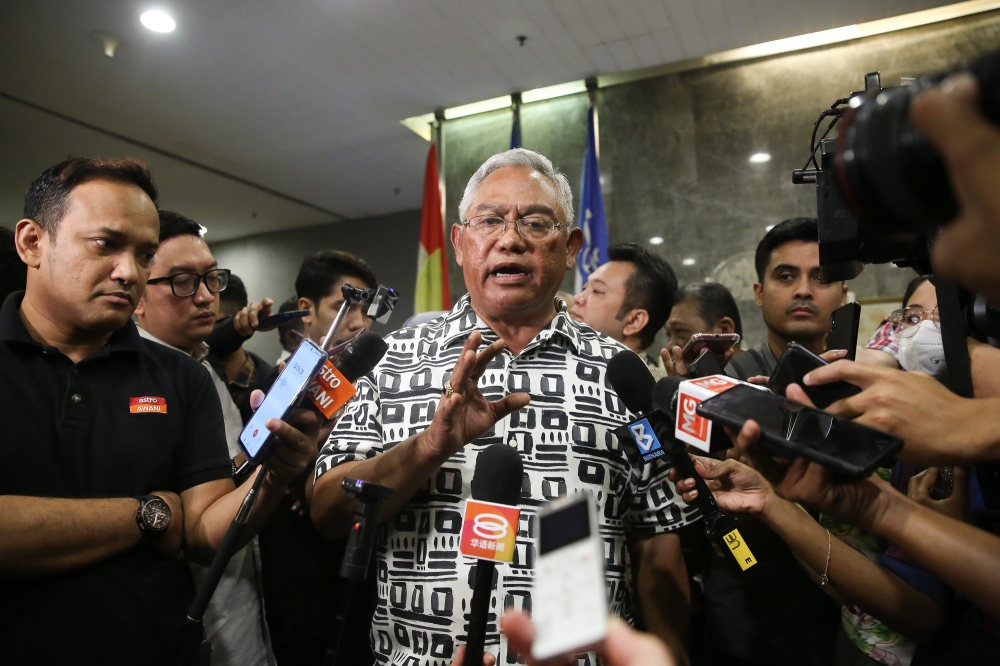

One could argue that Malaysia needs the ICC precisely because our rule of law is still poor. Malaysia had to change government before a former prime minister could be charged with corruption, as Datuk Seri Najib Razak allegedly suppressed investigations against him during his time in office.

According to the ICC’s “complementarity” principle, the court only exercises jurisdiction when a country’s own authorities are “unwilling or unable” to investigate and prosecute international crimes.

If that’s the case, then we should have enough self-confidence to repair our institutions, empower the judiciary, and improve rule of law in Malaysia so that we can conduct our own investigations and trials without resorting to a foreign court.

Malaysia should be a country that is willing to try its own leader, with specific procedures to investigate and remove a sitting prime minister from office.

The ICC has its own flaws too. Without its own police force, the ICC relies on countries’ co-operation to conduct investigations and to arrest suspects. Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who is wanted for genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur after ICC issued arrest warrants against him in 2009 and 2010, has yet to be handed over even though he has travelled to ICC member states.

The ICC has been accused of racism as most of its investigations focused on African countries. The court’s chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, however, has tried to change that by seeking the Afghanistan investigation, besides opening preliminary inquiries in Palestine and in Iraq involving alleged war crimes by UK nationals.

Last September, the ICC reportedly declared it could prosecute Myanmar over alleged crimes against humanity perpetrated on the Rohingyas, even though the country is not party to the Rome Statute.

This, I suppose, is one use of the ICC to Malaysia, who staunchly defends the Rohingya, and to Asean that has remained crippled over this issue.

But the ICC’s threat to Malaysian sovereignty still looms larger.

With limited resources and shrinking political capital, Pakatan Harapan should not bother too much with tricky international agreements and instead focus on regaining Malaysia’s internal strength so it can stand tall in the region.

*This is the personal opinion of the columnist.