KUALA LUMPUR, May 15 — The heart-wrenching image of a mother elephant desperately trying to rouse her lifeless calf after a highway collision has stirred the nation and the world.

The tragic scene shared widely on social media has reignited calls for wildlife corridors to be made a priority as development increasingly encroaches upon natural habitats.

Malaysia’s roads are no strangers to such devastating encounters.

Just last year, a male sun bear was killed while attempting to cross the East Coast Expressway 2, while another was filmed writhing in pain on the same highway in a separate incident.

In March 2024, a video showing the bloated carcass of a clouded leopard next to the West Coast Expressway’s divider also triggered public outcry.

These cases are not isolated.

As more land is cleared for housing, agriculture and infrastructure, animals are forced to navigate dangerous human dominated landscapes in search of food, water, or mates.

This has led to conservationists calling for the expansion of wildlife corridors dedicated paths that allow animals to move safely across fragmented habitats.

What is a wildlife corridor or animal crossing?

A wildlife corridor is a strip of natural habitat or a man-made structure that connects two or more large areas of forest or ecosystem.

It enables animals to migrate, breed, forage or escape threats such as fire and drought without being trapped or killed by roads, fences or human settlements.

These linkages are vital for ensuring genetic diversity among animal populations.

Without access to wider territories and other groups of the same species, animals become isolated, risking inbreeding, disease and eventual extinction.

How other countries are doing it

India, home to significant populations of elephants and tigers, has long recognised the value of protected corridors.

Without them, species like the tiger which requires a minimum breeding population of 80 to 100 individuals would struggle to survive due to shrinking and disconnected habitats.

The same goes for elephants.

Both animals are heavily protected and corridors are made specifically so they can move about freely without human contact.

Norway, on the other hand, has created an urban “bee highway” in Oslo, a network of green rooftops, parks, and beehives that helps pollinators navigate the cityscape.

Canada’s Banff National Park boasts 44 wildlife crossings along a single stretch of highway, combining fencing and overpasses to reduce vehicle-animal collisions.

The United States has also seen success with a variety of overpasses, underpasses and culverts that allow animals like deer, bears and cougars to safely navigate across highways.

Among the most used corridors are the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge both in Texas.

The US Highway 93 North Wildlife Crossing, Montana, Burnham Wildlife Corridor, Illinois and the Yellowstone to Yukon Wildlife Corridor are among the biggest wildlife corridors in the country.

What’s being done in Malaysia?

MRL-ECRL WBC boxes

One of the more ambitious projects currently underway is the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL).

Spanning 665 kilometres across Peninsular Malaysia, the ECRL slices through numerous ecologically sensitive areas.

Malaysia Rail Link (MRL) has committed to building 27 Wildlife Box Culverts (WBCs) along the route.

Eleven of these will be located within the Kemasul Forest Reserve, using just under 40 hectares of the more than 2,000-hectare forest.

The culverts, essentially tunnel-like structures, are designed to allow animals to pass underneath the railway line safely.

To monitor their effectiveness, MRL has installed hundreds of camera traps to track animal movements.

In a further show of commitment, China Communications Construction (ECRL) Sdn Bhd (CCCECRL) signed a collaboration with the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (Perhilitan) in 2023.

Under this partnership, a RM9 million Wildlife Management Plan was launched to study, monitor, and mitigate the rail line’s impact on nearby habitats.

West Coast Expressway installing box culverts

The West Coast Expressway (WCE) has also taken steps to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions.

Two large animal box culverts have been built at KM248.3 and KM249.7 of the highway, particularly where the road cuts through the Bubu Forest Reserve in Perak.

These structures, measuring 8 metres by 8 metres, are supplemented by PVC-coated chain-link fencing and raised barriers to prevent animals from wandering onto the tarmac.

These modifications aim to channel wildlife safely through the culverts rather than expose them to passing vehicles.

The Kuala Lumpur-Karak Expressway and the East Coast Expressway

On the Kuala Lumpur-Karak Expressway, wildlife underpasses have been constructed at multiple points, notably between KM33 and KM39, in proximity to the biodiverse Ulu Gombak Forest Reserve.

The East Coast Expressway also includes a viaduct system — elevated sections of road — from KM156.1 to KM162.7, giving animals room to cross beneath without danger.

Eco-viaducts on the Central Spine Road

The Central Spine Road (CSR) is a major highway linking Kuala Krai in Kelantan to Simpang Pelangai in Pahang.

As it intersects the Central Forest Spine, a key ecological corridor connecting four major forest complexes in Peninsular Malaysia, authorities incorporated eco-viaducts into its design.

The most impressive of these structures spans 900 metres at Sungai Yu in Kuala Lipis.

The viaducts offer a vital passageway for species like tapirs, sun bears, and elephants to travel between fragmented habitats, and are seen as a gold standard for balancing development with conservation.

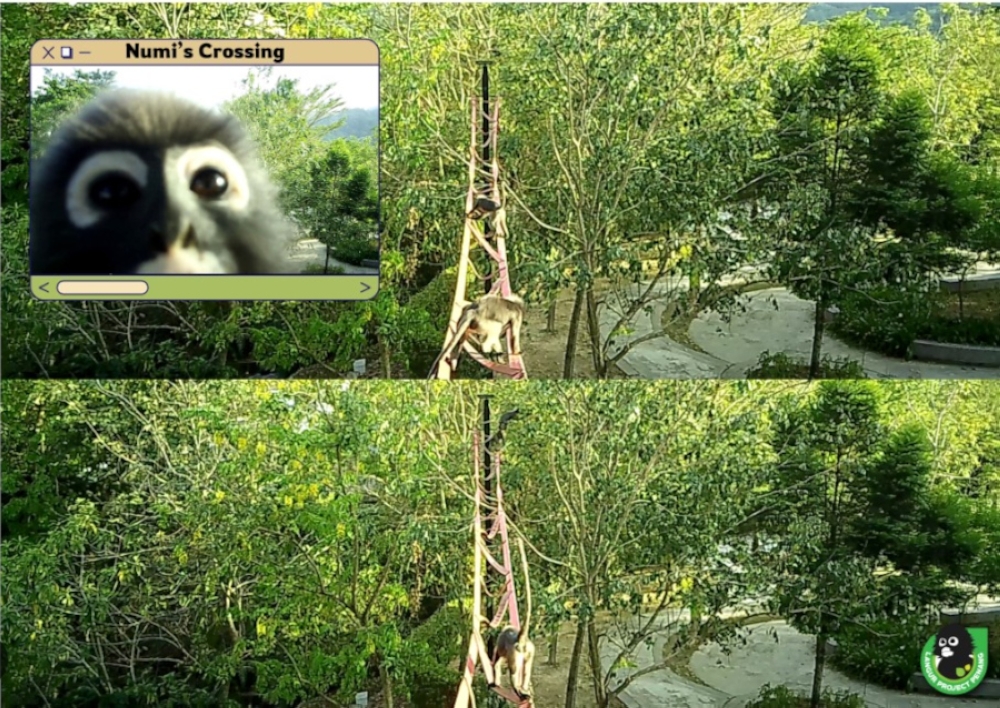

Numi and Ah Lai Crossing by Langur Project Penang

Over in Penang, conservation efforts have taken to the trees.

In Teluk Bahang, the Langur Project Penang (LPP) , a community science-based initiative led by wildlife researcher Dr Jo Leen Yap constructed Malaysia’s first artificial canopy bridge in 2019.

Designed specifically for arboreal species such as the endangered dusky langur, the rope bridge has recorded over 2,100 crossings by langurs, long-tailed macaques, and plantain squirrels.

Since its installation, there have been no reported primate roadkills in the area, a remarkable turnaround from previous years.

In February 2024, it marked one year since the launch of “Numi’s Crossing” in Lembah Permai, Tanjung Bungah.

Standing six metres high and stretching 12 metres across a road, the canopy bridge has already been used by dusky langur families to safely navigate their urban jungle.

Videos of these crossings have gone viral, offering both proof of concept and a potent emotional reminder of what’s at stake.

Sabah Softwoods Berhad wildlife corridors in Brumas, Tawau

In Sabah, home to the Bornean pygmy elephant — a subspecies already under threat — efforts to reduce human-elephant conflict have led to the creation of the Sabah Softwoods Berhad wildlife corridor in Brumas, Tawau.

Connecting the Ulu Kalumpang and Mount Louisa forest reserves, this 14 kilometre corridor varies in width from 400 to 800 metres and is designed to redirect elephant movement away from plantation areas, thereby reducing crop damage and protecting both elephants and humans.

Since 2022, the Malaysian Palm Oil Green Conservation Foundation (MPOGCF) has launched a campaign called “The Other Malaysian: Living Together in Harmony”.

This campaign aims to encourage oil palm plantation owners to coexist with wildlife within their plantation landscape.