KUALA LUMPUR, April 6 — For almost eight decades, the offence of attempted suicide has been a legacy of British colonialism in Malaysia’s criminal justice system, causing the mental health issue to be stigmatised and treated as any other crime under the law.

Now, Malaysia has finally taken the first concrete steps towards the full decriminalisation of attempted suicide, after proposed legislation to abolish the crime was put before Parliament the first time.

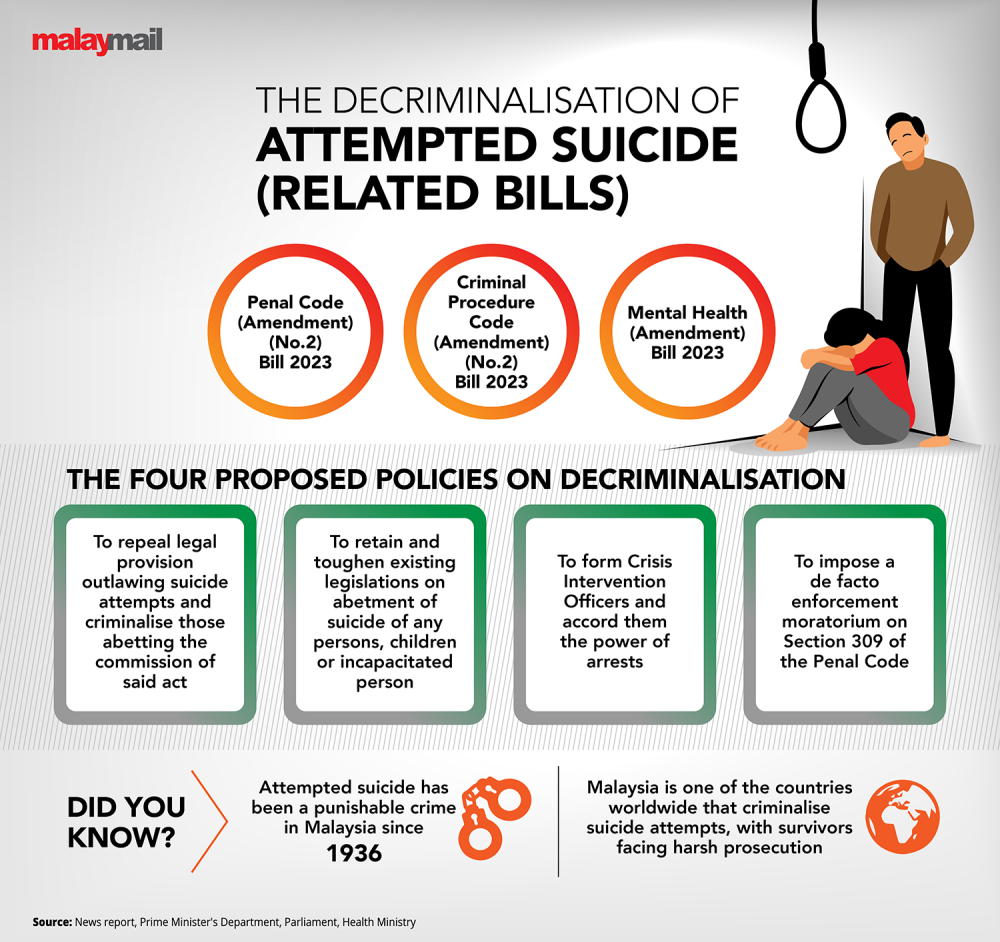

Three Bills — namely the Penal Code (Amendment) (No.2) Bill 2023, Criminal Procedure Code (Amendment) (No.2) 2023, and Mental Health (Amendment) Bill 2023 — were tabled for the first reading in the Dewan Rakyat by Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Law and Institutional Reform) Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said on April 4.

When tabling the Bills, Azalina said the move to decriminalise suicide attempts was among the federal government’s efforts to destigmatise the issue and encourage Malaysians to seek help rather than attempt to take their own lives.

“Criminal punishment is not the answer to mental health problems, which is why I am committed to reviewing Section 309 of the Penal Code,” Azalina previously said in a thread on Twitter last January.

In 2021, Azalina’s predecessor, Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, had indicated that the federal government intended to remove attempted suicide as a criminal offence in the country.

While it did not materialise then, the Bill tabled now to amend the Penal Code seeks to repeal the entirety of Section 309 that made attempted suicide a criminal offence and toughen existing legislation for its abetment.

Through the Bill, crisis intervention officers would be authorised to take into custody any person whom they have reason to believe was mentally disordered and a danger to themselves, other persons, or property.

In addition, these officers may employ forced entry into any premises to take such individuals into custody.

Unlike being arrested for a crime under the current law, however, the amendment proposed that such individuals be brought for evaluation at a government psychiatric hospital or a gazetted private facility within 24 hours instead.

The crisis intervention officers mentioned include police officers, fire officers, social welfare department officers and members of the Malaysian Civil Defence Force.

A de facto moratorium on the enforcement of Section 309 has also been proposed until full decriminalisation takes place.

For the amendments to take effect, the Bills must obtain approval by way of three readings from both the Dewan Rakyat and Dewan Negara, before being presented to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong for royal assent and subsequently gazetted.

The second reading of the Bills are expected to be debated in the next Dewan Rakyat session in May.

A brief history of Malaysia’s criminalisation of suicide

Deriving from the Indian Penal Code, attempted suicide was incorporated as a crime under the Penal Code (Section 309) when the legislation was first enacted by the British colonial administration during the reign of British Malaya in 1936.

Historically, attempted suicide had also been considered a punishable crime in England and Wales — whose sovereignty and direct rule of the British Crown were subsequently imposed in Malaya.

The act of “intentionally taking one’s own life” was also viewed as sinful by established religious tenets where it is forbidden in Islam and an act of blasphemy in Christianity.

In Malaysia, suicide is categorised as a criminal offence against the human body under the Penal Code.

Two other provisions namely — Section 305 and Section 306 — also made the abetment of suicide against children and incapacitated persons, respectively, criminal offences.

When Malaya achieved independence in 1957, it inherited the common law system introduced by the British and the aforementioned provisions saw little changes since then, with the only exception being Section 305 that was introduced in 1976.

Although the United Kingdom decriminalised suicide soon after in 1961, Malaysia has kept it as an offence punishable by the laws inherited from the former until now.

At present, Section 309 still provides for a prison term of up to one year, a fine, or both upon conviction; Section 305 is punishable by up to 20 years’ imprisonment and a fine; while Section 306 draws a penalty of no more than 10 years’ imprisonment and a fine.

What are the numbers?

According to the final annual report published by the now-defunct National Suicide Registry Malaysia (NSRM) in 2009, the suicide rate for the whole country when the population had been 27.8 million was 1.18 per 100,000 persons.

Officially launched in 2007, NSRM had extrapolated the number of suicides in Malaysia via a nationwide system of medical forensics units and departments.

However, medical experts believe the rate to be severely underestimated as it only captured data from medically certified deaths whose registrations bore evidence of the decedent’s intention to die.

Based on the NSRM report, individuals in 33.5 per cent of overall cases reported in 2009 had expressed their intention to commit suicide, with more than half or 55.2 per cent expressing it verbally.

Calls to decriminalise suicide was further cast into the spotlight in 2020 when the country entered a lockdown at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, with many reporting mental anguish exacerbated by the quarantine measures.

Last October, then-health-minister Khairy Jamaluddin said the number of suicidal cases linked to mental health had spiked significantly, rising over 80 per cent in 2021 (1,142 cases) compared to the previous year (631 cases).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) had in 2021 stated more than 700,000 people die to suicide annually and the body recognises suicide as a public health priority which is preventable with timely, evidence-based and often low-cost interventions.

*If you are lonely, distressed, or having negative thoughts, here are some services that offer free and confidential support 24 hours a day. Contact Befrienders KL at 03-76272929 or Talian Kasih at 15999 or Mental Health Psychosocial Support Service at 03-29359935.