KUALA LUMPUR, June 5 — Malaysia should not reintroduce a blanket moratorium or a freeze in loan repayments for all borrowers under the current total lockdown, as it is unnecessary and would not make financial sense when the government needs to ensure sufficient financial resources for the long fight against the Covid-19 pandemic, the finance minister argued today.

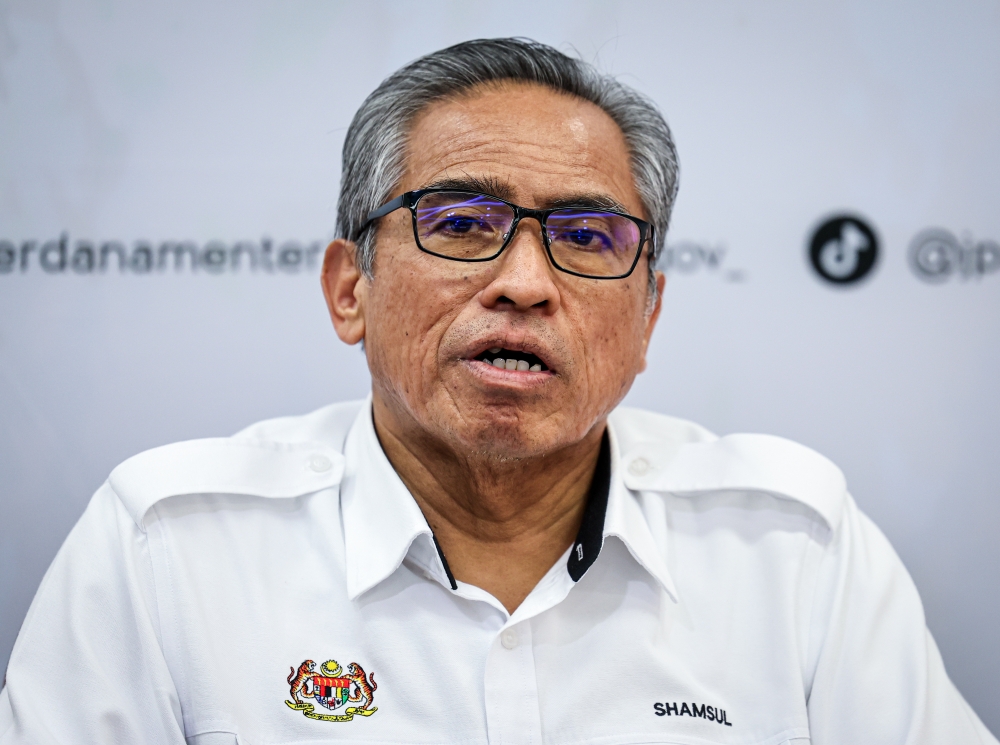

Finance Minister Datuk Seri Tengku Zafrul Aziz today wrote a lengthy statement to explain why it is not the best or most responsible move now for banks to suspend loan repayments for all borrowers instead of just those who need it, arguing that at least 80 per cent of borrowers in Malaysia do not need this and can continue repaying loans.

He said that borrowers in Malaysia that still need help repaying their loans currently can take up such help from banks — in the form of a three-month moratorium or a six-month reduction in loan repayments by half.

“Knowing that those who need temporary relief have options, and those who can afford it have resumed repayments, is a blanket moratorium the smart thing to reinstate, particularly when we know we must optimise our resources?” he asked.

“Most of us agree that fighting this Covid-19 war is more of a marathon than a sprint. Hence, why are we using a sledgehammer to crack a nut? Why are we deploying more resources than necessary if we know the journey ahead could potentially be both long and challenging?” he asked

His statement also included this phrase: “Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should.”

In his statement, Tengku Zafrul said the banks’ six-month automatic blanket moratorium last year under MCO 1.0 had benefited all borrowers, including those who are rich, the elite, big companies and even companies with massive profits.

He said about 85 per cent of borrowers in Malaysia resumed their loan repayments after the moratorium ended in September 2020, which he said was a strong indication that most Malaysians were able to continue paying their borrowings.

For the remaining 15 per cent borrowers who are struggling, Tengku Zafrul said the banks had then offered options such as three-month moratorium or a six-month reduction in loan repayments by half or other options tailored to their financial circumstances.

Noting the billions of ringgit of assistance and measures channelled by the government to help the public and businesses and signs of economic recovery with the gross domestic product in March 2021 at +6 per cent, Tengku Zafrul went on to say that banks are currently still offering assistance to borrowers who need help in repaying their loans.

This Loan Repayment Assistance (LRA) offers the options of a three-month moratorium or a six-month 50 per cent reduction in monthly loan installment, and is available to all jobless individuals, those in the M40 and T20 group with reduced income, B40 or low-income recipients of government aid under Bantuan Prihatin Rakyat, micro small medium enterprises (micro SMEs) with loans up to RM150,000, and SMEs and micro enterprises that are part of economic sectors that are locked down during MCO 3.0.

He said such borrowers will receive automatic approval when applying for either option, and that the banks have agreed that any distressed borrower will never be turned away during these tough times.

The LRA is currently in place instead of the blanket moratorium that was in place last year.

Compensation, investor confidence, new banking crisis

Tengku Zafrul clarified that the finance minister of Malaysia does not have the authority under two laws — the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009 (CBA) and the Financial Services Act 2013 (FSA) — to instruct banks to give an automatic moratorium for loans.

While the Emergency (Essential Powers) Ordinance 2021’s Section 4 does give the government the powers to mobilise any resources necessary for public good, he noted that any such compulsory action by the government requires compensation to the party that yielded its resources.

“In short, this cannot be done at zero cost to the government,” he said.

“But just because we can, does that mean we should? Repeating the blanket moratorium also means that the government may need to significantly compensate banks for a measure that was not even necessary in the first place.

“How does this make financial sense, particularly in a resource-tight situation for a potentially lengthy war against an enemy that can mutate without warning? I would rather direct those resources in the form of aid or subsidies to the rakyat and business segment that need them the most,” he said when speaking of the need to conserve the government’s financial resources for the long Covid-19 fight and using government funds to help the public instead.

Even if the government decided to play the “populist card” and forced the country’s business community to reimpose measures such as a blanket moratorium, Tengku Zafrul highlighted the risks of investors’ confidence being affected in Malaysia’s policies for the long-term.

As the rule of law is necessary for a stable market, the minister said the government’s indiscriminate invoking of Emergency powers may result in parties being forced to break or amend contracts, which he said would in turn seriously impact future business and investments.

“This may also have far-reaching implications which may lead to a run on our capital markets, and cause an outflow of funds which could, in turn, affect the ringgit’s value and increase the cost of doing business, collectively causing grave, long-term repercussions to our economy. We already have a public health and economic crisis to manage; why throw a potential financial and banking crisis into the mix?

“Is it neither fair nor responsible for the government to take all these risks just for the sake of enabling a blanket moratorium for everyone, particularly when we know that at least 80 per cent of borrowers do not need it, and banks are already giving or offering targeted assistance to borrowers that really require this relief,” he argued.

Avoiding self-destructive move

He also suggested that bringing back a blanket moratorium would end up hurting the public itself, as the key investors or largest shareholders of banks in Malaysia are actually public institutions investing and managing funds on behalf of Malaysia.

“This unnecessary self-destructive, over-specified solution to the issue at hand is like cutting off our nose to spite our face,” he said.

He noted these key shareholders in banks to be institutions like Employees Provident Fund (EPF) and Retirement Fund (Incorporated) (KWAP) which manage retirement funds for the private sector workers and the civil servants respectively, Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) which issues unit trust funds for Malaysians, Lembaga Tabung Haji which manages savings belonging to Muslims, Socso which manages a social security fund for workers, and insurance companies and fund managers managing investments for Malaysians.

“In short, it is the general rakyat who ‘own’ the banks, albeit by proxy via entities like EPF and PNB. Ultimately, it is the rakyat who will get lower dividends from EPF, ASB or Tabung Haji etc., if banks suffered losses through, say, a blanket moratorium,” he said.

He suggested that not having a blanket moratorium but only helping borrowers in need would be the “best win-win situation”, as this would protect depositors, shareholders and borrowers, while also ensuring that capital or funds in the financial market ecosystem is used efficiently to grow the economy.

He had explained that a blanket moratorium would not receive loan repayments from borrowers in order to lend to other borrowers, while at the same time still having to continue paying interest to depositors’ whose funds were used to lend to borrowers.

He also explained that bank profits are used to build up buffers so that banks can continue to give out loans to support the economy despite losses from loans, and that lending would be severely constrained if there are no such buffers and would disrupt the cycle and stop the economic benefits created from efficient movement of funds or capital.

“Part of my responsibility as a Finance Minister is to avoid decision-making based on narrow short-term interests meant to serve a populist agenda, and do what is right for the rakyat, our market stability and the country’s long-term benefit,” he also said in conclusion.

His lengthy statement was published in English by The Star as “Why use a sledgehammer to crack a nut?” and in Bahasa Malaysia by Sinar Harian as “Jangan guna belantan hanya untuk memukul nyamuk di badan”.

.jpg)