KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 10 — As of today, at least four people have either been sacked, suspended or resigned from their jobs after being accused of insulting Sultan Muhammad V who resigned as Yang di-Pertuan Agong (YDPA) just three days ago.

At least three of them have been arrested by the police, and investigated under Section 4(1) of the Sedition Act 1948. If convicted, the first-time offenders may be fined not more than RM5,000, jailed for not more than three years, or both.

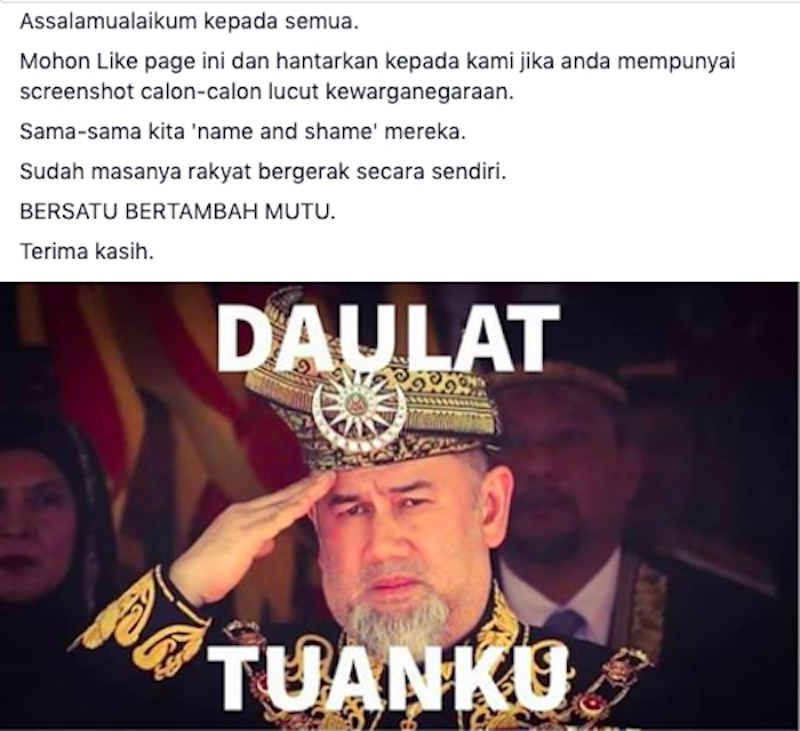

While they were all accused of insulting the YDPA on social media, they were also victims of a practice called “doxing”, as part of a kind of vigilantism by an online group who has taken it upon itself to defend the honour of the Malay Rulers.

All four of them were named in a list on a Facebook page that has been liked by 13,670 users (at the time of writing) since it went up on Sunday. So far, eight targets have been listed by the page.

Subsequently, the arrests have only emboldened the group; it thanked the police for their action as soon as Inspector-General of Police Tan Sri Muhammad Fuzi Harun released a statement announcing the move.

“We are ready to be your eyes and ears,” said a post on the page.

What is doxing?

Doxing or doxxing, a term originating from the word “documents”, includes harvesting private information from publicly available data online or social media, and broadcasting such information, usually to identify someone.

In his 2015 article titled “The rise of political doxing”, internationally renowned security technologist Bruce Scheier said the practice has since been used as a tool to harass and intimidate people, primarily women, on the Internet — and increasingly to ruin someone’s reputation.

“This is relatively easy in Malaysia because many share personal identifiable information on social media, often on the same accounts they use to post content that make them the target of doxing,” Khairil Yusof, the co-ordinator of technology activist group Sinar Project, told Malay Mail.

Security expert Keith Rozario also highlighted the difference between someone stumbling upon another’s personal information online, versus someone making a concerted effort of finding and consolidating as much of that personal data — and then publishing that with the intention to harm the target.

“It’s far easier to get data on someone today than it was three to five years ago, and certainly far easier today then it was before smartphones and social media,” he added.

There is nothing subtle about doxing. When listing its first target, Eric Liew, the page not only listed his workplace Cisco Asean — which has since clarified Liew is no longer employed there — but also his photo and position, obtained from his LinkedIn professional network profile.

For its second target, a doctor at the Mediviron chain of private clinics who has since been forced to resign, the page also displayed his public photos, other social media accounts, and details from his practising certificate.

A similar trend was spotted when it came to the targets. Usually, screenshots of comments posted by the targets on other social media posts are included.

In some cases, the page would personally contact the targets’ employers through social media in a bid to pressure action from them — as in the case with Cisco Asean.

The page encourages followers to submit anybody deemed suitable as targets to be added to its list.

Followers also regularly post screenshots of comments from those they feel should be targeted, some even with additional information of the targets like the personal address of their homes — asking the page to “punish” and “teach them a lesson”.

To gather these comments, followers inform each other to “camp” at the Facebook pages of certain news outlets, such as Malay Mail itself, Malaysiakini, Free Malaysia Today, and The Malaysian Insight.

“Use Google Translate,” one commenter said urging others to monitor comments in Chinese.

Commenters were also not shy about their motivation.

“It doesn’t matter if the police makes an arrest or not. What’s important is for us to grab and wallop them, even when they are freed,” said a top comment in one of the page’s post.

“Okay to be racist. As long as we have pride,” said another top commenter in another post.

An eye for an eye

On Sunday, Kelantan’s Sultan Muhammad V stepped down as YDPA, just days after he returned from his two-month medical leave.

His decision came days after the Malay Rulers reportedly convened a rare unofficial meeting on Wednesday night for a serious discussion on an undisclosed matter.

The Conference of Rulers will now meet on January 24 to elect the new YDPA and his deputy, to be sworn in on January 31.

Civil liberties lawyer Syahredzan Johan believes that the current vigilantism is a response to the case of “Edi Rejang”, who was sacked and investigated by police after harassing an ethnic Chinese beer promoter.

In November last year, Mohamad Edi Mohamad Rias uploaded a video of himself approaching the promoter to confront her for performing her job in the non-halal section of the hypermarket; he swore at her after failing to goad her into responding.

“I think what happened to Edi Rejang has 'inspired' this manufactured outrage,” said the political secretary to DAP MP Lim Kit Siang.

Apart from the arrests, Datuk Mohd Tamrin Abdul Ghafar was also questioned for three hours over two blog posts relating to Sultan Muhammad V earlier this week.

Yesterday, Malay rights group Perkasa urged Putrajaya to adopt its suggestion of an explicit lèse-majesté law, a so-called “anti-Islam and anti-Malay rulers” Act, with punishments of mandatory jailing and whipping.

This is Part One of a two-part story. To continue to Part Two, “‘Hunt’ for critics of monarchy: So what does the law say about ‘doxing’?”, please click here.