GEORGE TOWN, March 4 — Ever since George Town was accorded world heritage status in 2008, many of its long-time inhabitants have been forced to leave their city homes due to increased rentals and in some cases, eviction.

Since the year started, 55 tenants have received notice of a 200 to 300 per cent hike to their monthly rental. Many run small businesses from these heritage shop-houses and find it tough-going to afford the new rates, which will shoot up their rental from under RM500 to over RM1,500 overnight.

Those able and willing to cough up the money however, are having a hard time staying on as their landlords seek to gentrify their buildings that have turned the Penang port city into a tourism magnet.

“We don’t mind paying the extra rent because my mother is so used to living here. It will be difficult to ask her to move out,” said one of the affected tenants, Teong Han Yen.

His 85-year-old mother, Kim Swee Ngoh, moved into their double-storey premises along Penang Road when she got married at age 19. It has been where for over 66 years she helped her now deceased husband run a shoe shop and raised their family. Despite repeated coaxes from her other children to live with them in their homes outside the city, she steadfastly refused to do so.

Today, Teong and his mother still run the shoe shop, which now also sells clothes, bags and a variety of items to attract tourists wandering the historic city. With revenue from the business, they are able to make a small living that will just about cover the revised rent for two lots. It used to be RM1,300 a month. It’s now RM4,000.

“Locals don’t shop here anymore, not like my father’s time when our shop was always abuzz with people shopping for shoes and Japanese slippers. My father’s shop is the first to bring in Japanese slippers at that time in the 1960s,” Teong said.

The shop was originally a sundry shop opened by Teong’s grandfather who started renting the place in 1922. When the shop was handed over to his father, it was converted into a shoe shop.

“We don’t even get as many tourists here. In fact, we depended a lot on foreign workers who would buy shoes and slippers from us because our things are cheaper,” Teong said.

A total 34 shops and households decided to move out of George Town last month. The latest departures mean roughly 1,000 people have left the city since 2009. A baseline study showed that 800 people had already moved out between 2009 and 2013 due to various reasons.

According to its report conducted on 2009 and 2013, the population decline led to a related decline in the number of businesses servicing households.

The same report pointed out that there is a shift in the population living in the heritage zone with an increase in the number of migrants working and living in the same zone even as local residents move out.

Another affected tenant who is on a monthly rental contract basis for now is Siew Thean Moh. The 62-year-old said he and his household wanted to stay even though rental was increased from RM450 to RM1,500.

“The owner’s management people came and told us to leave because our shop doesn’t look nice and doesn’t fit with their concept,” he said.

Siew runs Siew Brothers Enterprise, supplying burger patties and other ingredients to street food vendors from out of an old shophouse along Kimberley Street.

“Since they told us to move out and the contract is on a monthly basis, we have to look for another place nearby to move,” he said, adding that they may have to move to another shophouse in the city for a RM1,800 monthly rent.

The burger supplies shop has been in the shophouse for over 40 years but Siew only took over the business about 12 years ago.

George Town World Heritage Inc (GTWHI) along with the Komtar assemblyman Teh Lai Heng are currently in the midst of discussions with house owners and tenants to find an amicable resolution to this issue.

GTWHI said it is aware of the mass exodus of long-time residents and traders due to increased rentals and evictions in recent years.

However, it said there are currently no laws that protect the rights of long-time tenants from rampant increases in rent or from evictions.

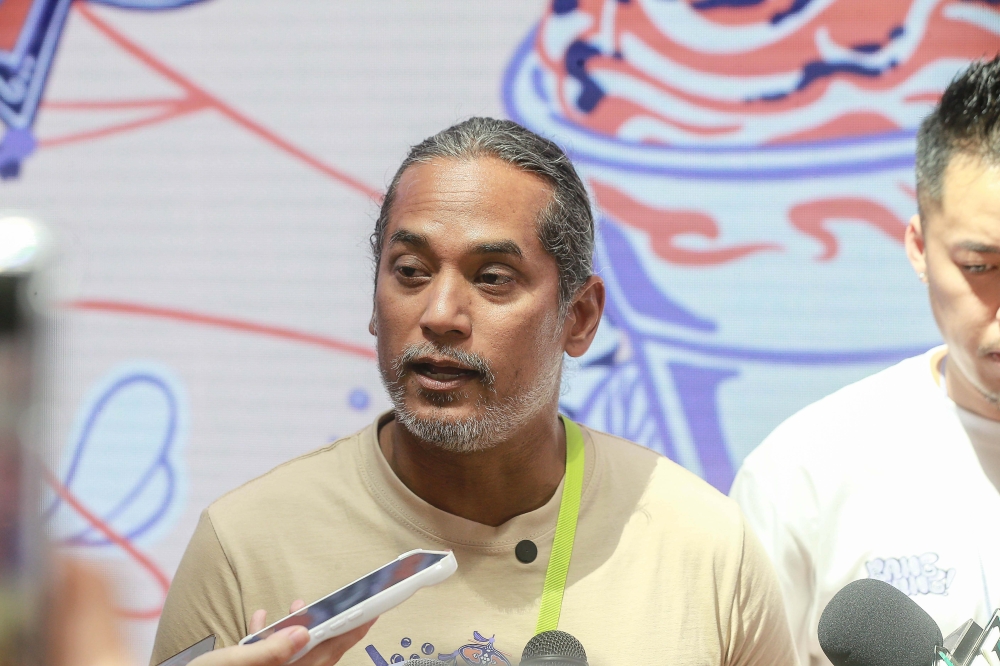

GTWHI general manager Dr Ang Ming Chee said the residents, trades, their cultures and way of living are one of the city’s Outstanding Universal Values (OUV) that should be safeguarded but in order to do so, meticulous documentation needed to be done first.

She said they have been conducting video and oral documentation of the history of local residents and traditional trades in the heritage zone but it is not an easy task.

“It took my officers three months to gain the trust of some residents before they are willing to open up to talk to us,” she said.

She said conducting the documentation is especially difficult when residents often eye government officials with suspicion and are usually reluctant to reveal anything.

“GTWHI will continue the documentation this year and the cataloguing of other components of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) in George Town World Heritage Site will also be carried out this year,” she added in an interview with Malay Mail Online.

She explained that the identification of these components of ICH is important precursors for GTWHI to address the issues of ICH sustainability in the city.

“We can only come up with action plans and strategies to safeguard the city’s ICH when we have the facts on hand,” she said.

Ang said the best case scenario is to have an open information system where the rental rate of every house in the city is publicly available so that tenants could compare and demand for fairer prices from their landlords.

She said the community must also take up their roles to support local traders and stand up to unite all residents against unfair increases in rental rates.

“Safeguarding the ICH is not easy and we can’t be doing it alone without the community getting involved to safeguard their own heritage,” she said.