KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 10 — Once dismissed as vandalism or visual novelty, graffiti, murals and public art have over the past decade reshaped how Malaysians encounter art — not in art galleries, but on streets, bridges, drains and building facades.

From George Town’s iconic murals by Ernest Zacharevic to sprawling graffiti projects across the country, public art has evolved into a shared visual language of place, people and identity.

But as walls fill up and murals age, one main question arises: what comes after murals?

Public perception

For Penang Art District general manager Kenny Ng, the future of public art lies not in scale or spectacle, but in rethinking its purpose altogether.

“Public art has shifted over time, from civic idealism to creative placemaking and, in many cases, city branding,” he said.

“The next step isn’t about more murals or bigger sculptures, but about rethinking its purpose and agency,” he added.

Ng believes public art must move beyond object-based works towards process-driven, people-centred practices such as art that evolves over time, involves communities meaningfully and responds to real social contexts rather than merely decorating space.

That idea of public art as something lived rather than displayed echoes strongly with Zacharevic.

While Zacharevic is often credited with popularising mural culture locally, he remains cautious about prescribing what comes next.

“That’s something only time can reveal. Artistic forms and mediums are constantly changing. What remains constant is that as long as there are people, there will be art,” he said.

Yet even as public art continues to evolve, debates around preservation and permanence persist. Should murals be conserved as cultural assets, or allowed to fade naturally?

Beauty in impermanence

“There is beauty in ephemerality. Sometimes temporality makes a work more meaningful,” Zacharevic said.

“That said, when certain artworks become deeply embedded in a city’s identity, it becomes difficult to imagine that place without them,” he added.

In September 2024, Zacharevic was commissioned by the Penang state government to restore three of his famed murals located along Cannon Street (Boy on Chair), Armenian Street (Children on Bicycle) and Ah Quee Street (Boy on Motorcycle).

He had previously restored the murals in 2016 and again restored Children on Bicycle after it was vandalised in 2019.

Ng agrees that permanence should never be a default expectation.

“Public art doesn’t have to be permanent to be meaningful. Some works are meant to last, others are intentionally temporary,” he said.

He said any decision on the murals should be guided by the artist’s intent and the work’s cultural or social significance.

Both Ng and Zacharevic stress that responsibility cannot rest on a single party.

Instead, it must be shared between artists, government bodies, institutions, developers and most importantly, the communities who live with these works.

For artists rooted in graffiti culture, that tension between permanence and impermanence has always existed.

Local artistry

Local artist Sliz, who began doing paid murals in 2012, estimates he has completed 50 to 70 commissioned murals locally, alongside more than a hundred unpaid or self-funded graffiti works.

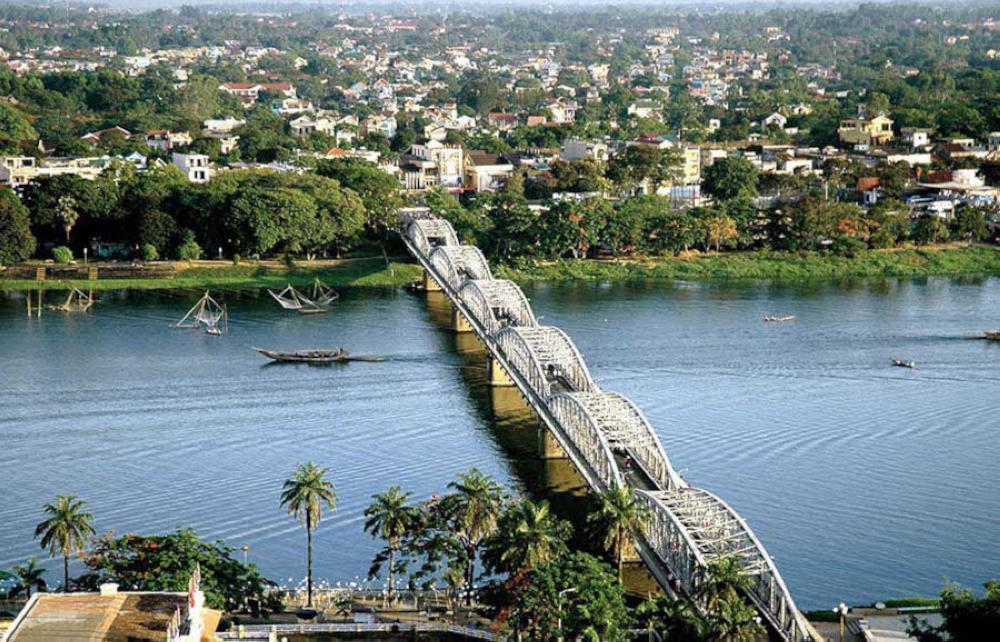

While he has painted abroad in cities such as Singapore, Mumbai and Hanoi, his practice remains deeply tied to the streets.

“I think there’s a wide gap between what is defined as murals or public art, and what graffiti is as a culture,” he said.

“For many of us who started from graffiti and vandalism, we were already going through our own ‘next step’ before these terms even existed,” he added.

He points to an uneasy interdependence between public art as a real-estate or branding tool and graffiti as a culture rooted in community and place, something he feels deserves more professional dialogue.

As someone shaped by graffiti’s temporary nature, Sliz sees no single right answer when it comes to maintenance.

“I love public art,” he said.

“I appreciate the temporary-ness of things, but at the same time, I still strive to leave a long-lasting mark whenever I can,” he added.

That balance between passion, profession and responsibility is something graffiti artist Muhammad Fakhrul Akmal Shamsurrijal knows well.

The 38-year-old artist, known as Mile09, began doing graffiti in high school before quitting a stable advertising job in 2010 to pursue mural work full-time.

“At first, I didn’t see graffiti as a career. It was strictly a passion,” he said.

“But after being commissioned for several jobs, I realised I could actually make a living out of this,” he added.

Since then, his work has appeared across Malaysia and abroad, from a 300-metre mural at a Royal Malaysian Air Force base to a one-kilometre underpass project in the UAE.

Recognising value

For Akmal, public art’s value goes far beyond aesthetics.

In Kuala Terengganu, murals he painted on bridge pillars ended up helping fishermen identify deep and shallow waters.

In Kuala Lumpur, graffiti transformed a former addicts’ den near an LRT station into a safer, creative space now used for filming and public activity.

“These artworks really changed the whole vibe of the area,” he said.

Still, Akmal is candid about the realities behind large-scale public art: from safety risks to material costs.

After falling from unstable scaffolding early in his career, he now insists on high-quality safety equipment, even when it cuts into his earnings.

He is equally vocal about the need for better materials and fairer budgets.

“If you use cheap materials, the artwork might last a year,” he said.

“With the right materials, it could last seven years or more. Companies need to think long-term.”

Like Ng, Akmal believes that appreciation for public art cannot rely on visibility alone.

“It’s okay to give artists creative freedom,” he said.

“Let them interpret the work. That’s how you nurture talent and keep ideas growing,” he said.

As murals continue to attract tourists, shape neighbourhoods and spark debate, one thing is clear: public art in Malaysia is no longer just about painting walls.

It is about access, ownership, safety, storytelling and community and about deciding, collectively, what kind of visual legacy cities want to leave behind once the paint begins to fade.