PARIS, Nov 15 — Although essential for good health, the sodium contained in table salt and in certain foods can be harmful when consumed in excess. In particular, it increases the risk of stroke and premature death.

A new study reveals that removing just a tiny amount of salt from the daily diet can lower blood pressure, with “a decline comparable to [the] effect achieved with drugs.”

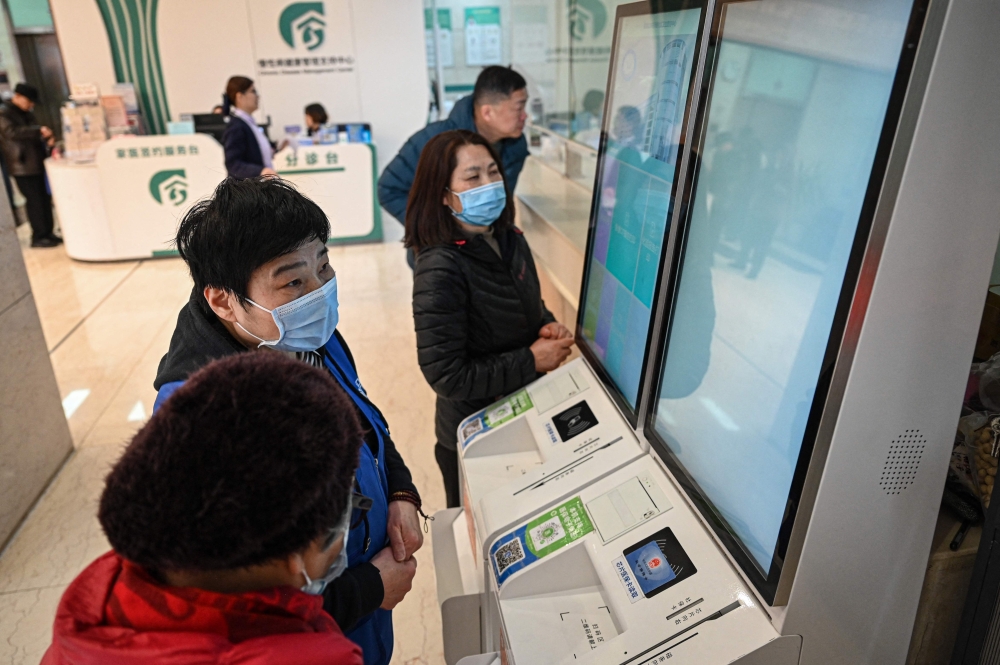

Adults should consume no more than 5 grams of salt per day (equivalent to 2 grams of sodium), or one teaspoon, according to World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines, but the health authority estimates that the global average is 10.8 grams.

“Eating too much salt makes it the top risk factor for diet and nutrition-related deaths.

More evidence is emerging documenting links between high sodium intake and increased risk of other health conditions such as gastric cancer, obesity, osteoporosis and kidney disease,” the WHO warns.

It adds that the implementation of sodium reduction policies in all regions of the world “could save an estimated 7 million lives globally by 2030.”

A team of researchers from Northwestern Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Centre and the University of Alabama at Birmingham examined this issue.

They based their study not on WHO recommendations, but on the total daily sodium intake recommended by the American Heart Association (AHA), which advises not exceeding 2.3 grams per day, while aiming for an ideal limit of 1.5 grams.

The scientists sought to assess the effect of lowering sodium in the participants’ diets on blood pressure, including in people being treated for hypertension.

A teaspoon of salt

The study followed 213 individuals aged between 50 and 75 from two US cities (Birmingham and Chicago), who were randomly divided into two groups: the first was asked to adopt a high-sodium diet (2.2 grams per day in addition to their usual diet), and the second a low-sodium diet (0.5 grams in total per day) for one week.

Each group was then swapped onto the other diet for a week. In both cases, analysis was carried out to measure systolic blood pressure. Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the study reports that systolic blood pressure fell by an average of 7 to 8 millimetres of mercury on the low-sodium diet, compared with the second diet, and by 6 millimetres of mercury compared with the participants’ usual diet.

This concerned no less than 72 per cent of the people included in the study.

“In the study, middle-aged to elderly participants reduced their salt intake by about 1 teaspoon a day compared with their usual diet.

The result was a decline in systolic blood pressure by about 6 millimetres of mercury (mm Hg), which is comparable to the effect produced by a commonly utilised first-line medication for high blood pressure,” said Dr Deepak Gupta, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Centre and co-principal investigator.

The scientist’s comments should only be taken in the context of the study, but they nevertheless highlight the impact that lowering salt, and therefore sodium, consumption can have day to day.

“The fact that blood pressure dropped so significantly in just one week and was well tolerated is important and emphasises the potential public health impact of dietary sodium reduction in the population, given that high blood pressure is such a huge health issue worldwide,” said co-investigator Dr Cora Lewis, professor and chair of the department of epidemiology and professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

According to the WHO, nearly 1.3 billion people aged between 30 and 79 suffer from hypertension worldwide, almost half of whom are unaware of it.

Adopting a low-salt diet is one of the global health authority’s recommendations for combating hypertension, along with weight loss, physical activity and quitting smoking. — ETX Studio