PETALING JAYA, Oct 13 — What does it mean to give a modern take on a centuries-old tale?

Local authors have always drunk from a rich well of folklore for their work, drawing inspiration from brave warriors depicted in the Malay hikayat and the grace and intelligence of legendary princesses like Puteri Gunung Ledang.

Some folktales even have the power to ignite debates over pressing modern-day issues such as racism and colourism, as seen in the 2020 drama Dayang Senandung which featured a Malaysian actress in blackface playing the role of a princess “cursed” with dark skin.

But what is it about these tales that continue to provoke the imagination hundreds of years after they were first uttered by our ancestors?

These are some of the questions that Malaysian writers like Joshua Kam and Ninot Aziz explore in their work.

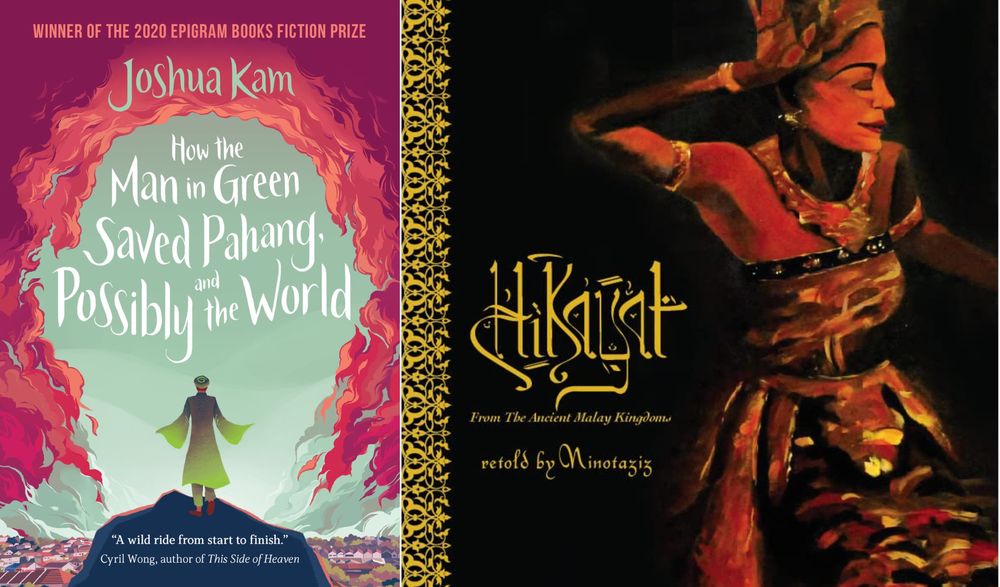

Kam made headlines when he became the youngest person to win Singapore’s prestigious Epigram Books Fiction Prize in January this year at the age of 23.

His debut novel How the Man in Green Saved Pahang, and Possibly the World is based on Malay hikayat and brings readers on a rollercoaster ride in a world populated with Sufi saints, plainclothes gods, and shadowy serpents.

In an interview with Malay Mail, Kam said he wanted to use established folktales as a medium to say something new about the country he grew up in.

He added that the book did not attempt to describe things as they were spelt out in Hikayat Hang Tuah, or even in his grandmother’s stories because he wanted to say new things about Malaysia today.

“I think one of the biggest insights I learned from those writers of the past was just the sheer diversity of our tradition and traditions.

“The deeper you dig, the less certain you are that our national Malaysian narrative is as polished as we assume.

“Our tanah air is bigger than I ever imagined, and I hope other misfit Malaysians can draw hope from that as I have,” said Kam.

Currently based in the United States, Kam said folktales have been an integral part of his identity growing up in a Christian-Buddhist household in Kuala Lumpur.

As Malaysia moves forward into the future, Kam hopes to reclaim the stories of its ancestors instead of leaving them in the past.

Keeping the past alive

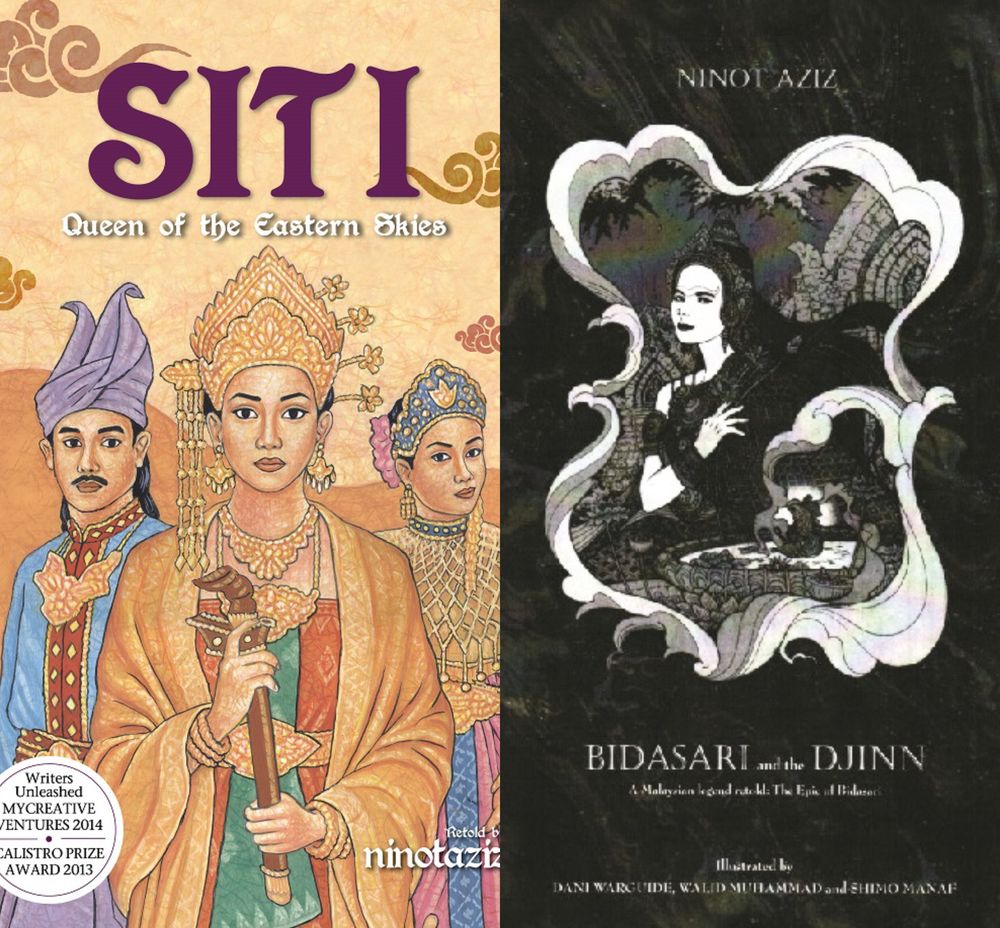

Kam’s aim to revive Malaysia’s repertoire of myth and folklore is one shared by his fellow author Ninot Aziz, who is best known for her illustrated anthology From the Written Stone: An Anthology of Malaysian Folklore and the young adult novel Kirana: Dreams After the Rose.

Ninot, born Zalina Abdul Aziz, was spurred to write about local legends after experiencing the magic of a Mak Yong performance and realising that many Malaysians were more familiar with foreign legends rather than ones from their home country.

“When my first daughter was about seven years old, I realised she only knew Western fairytales as well as Egyptian and Greek legends.

“That was also when I knew I wanted to collate and retell our legends,” she told Malay Mail.

Ninot believes that Malaysians have much to learn from local legends and her writing often focuses on iconic women such as Hang Li Po, Che Siti Wan Kembang, and Puteri Gunung Ledang to name a few.

She hopes to inspire readers, especially children, with the legacy of these characters and forge stronger ties between Malaysians and their heritage.

“Our queens and princesses were strong rulers capable of leading an army, conducting trade, and keeping peace and harmony.

“We have inherited this and it’s the reason why our young girls must know our stories.

“Men would also do well to respect and love unreservedly such progressive and strong women.”

A creative medium for the past and present

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia senior lecturer in cultural anthropology Vivien Yew Wong Chin said folktales remain culturally prevalent today as many of them contain timeless narratives that resonate with both young and old.

“Folktales are the creation of human beings. They may have or may not have happened.

“Even though it had some degree of fantasy elements, the theme or the main plot of the story is set in a real-life scenario in a particular era to give some semblance of familiarity and believability to its readers to gain popularity,” Yew told Malay Mail.

With authors, filmmakers, and artists consistently turning to local myths and legends for inspiration, these tales garner the potential to express contemporary views while acting as a bridge between modern-day society and its past.

Yew believes that this hybrid quality, observed in both Kam’s and Ninot’s writing, affords folktales the ability to live on even as the cultural and sociopolitical landscape shifts throughout the years.

“From an anthropological perspective, folktales are timeless and placeless because they are set in any time and place.

“They continue to evolve and never cease to be relevant even in modern times because folktales are shaped according to the conditions of the times.”

She added that indigenous knowledge coupled with traditional norms and beliefs in folktales kept generations of people connected to their traditions and helped shape a particular culture.

“Fundamentally, folktales are the production of the folk, the masses, and the people. Thus, the nature of the folktales naturally resists any ideological construct.”