JANUARY 18 — You can reject a view without arresting the person who expressed it.

Yet in Malaysia, that distinction still appears fragile. The arrest involving an ex-reporter shows how quickly disagreement can escalate into a police matter, when it should have remained a public debate.

Let me be clear from the outset. I do not agree with the substance of his views.

They are shallow, intellectually unconvincing, and offer little by way of serious engagement with Malaysia’s complex social and political realities.

But disagreement, even strong disagreement, is not a crime. Treating it as one is not only unnecessary; it is corrosive.

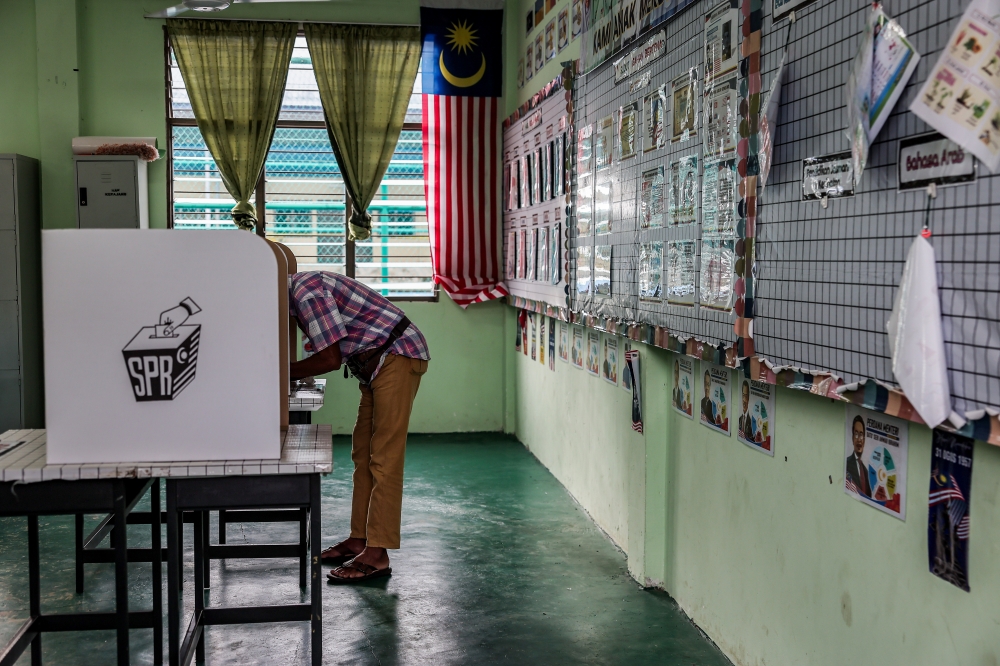

Malaysia has long struggled with a habit of responding to speech it finds uncomfortable not through argument, rebuttal, or public reasoning, but through legal instruments.

This habit has lingered, sometimes quietly, sometimes blatantly, into the post-reform era. Each time it resurfaces, it sends a troubling signal; that the state lacks confidence in public debate.

From a democratic theory perspective, this is not a trivial concern. Political theorists from John Stuart Mill to Jürgen Habermas have long argued that the legitimacy of a political order rests not on the absence of offensive speech, but on its ability to withstand it.

Mill’s harm principle reminds us that expression should only be curtailed when it causes direct and tangible harm, not merely because it offends sensibilities, challenges dominant narratives, or exposes intellectual fragility.

Habermas, meanwhile, places public reasoning at the heart of democratic legitimacy. Arrest short-circuits that process.

What makes this case particularly troubling is its disproportion. The views were not violent.

Treating them as a security issue turns a minor controversy into a state problem, and exposes how thin the line still is between disagreement and enforcement.

The decision to arrest, therefore, reveals less about the speech itself and more about institutional insecurity.

There is a hard truth Malaysia must confront. When the state reacts punitively to weak arguments, it elevates them.

Arrest transforms marginal views into symbols of repression. It grants attention, sympathy, and legitimacy that the ideas themselves would never earn through merit. In this sense, enforcement becomes amplification.

More dangerously, it reinforces a culture of fear among journalists, commentators, and citizens who may hold far more thoughtful, critical, or necessary views.

If shallow opinions trigger arrest, what happens to rigorous critique? What happens to dissent that is evidence-based, morally demanding, and politically inconvenient?

Democratic maturity is not measured by how well a government silences “bad” speech, but by how confidently it allows society to dismantle it through debate.

A confident democracy trusts its citizens to judge ideas. An insecure one relies on coercion.

Malaysia today sits uneasily between these two models. On paper, we speak the language of reform, rights, and institutional renewal.

In practice, we often revert to securitised thinking, where speech is treated as a threat rather than a contribution to public life.

This contradiction weakens not only freedom of expression but the credibility of democratic governance itself.

Importantly, defending the space for expression does not require defending the content of every expression.

This is a distinction Malaysia has yet to internalise. One can reject an argument as intellectually weak while defending the speaker’s right to make it.

In fact, doing so strengthens democratic culture by modelling how disagreement should function, through critique, not coercion.

What would a more mature response have looked like? Editorial rebuttals. Scholarly critique. Civil society responses. Public forums. Silence, even, letting an idea wither from lack of substance.

All of these would have demonstrated confidence. Arrest demonstrates the opposite.

The deeper issue, then, is not the ex-reporter alone. It is our persistent inability to tolerate discomfort without reaching for the law.

Until Malaysia learns to separate offence from harm, disagreement from danger, and critique from criminality, we will remain trapped in a cycle where power fears speech, and in doing so, reveals its own fragility.

If democracy is to mean anything beyond procedure, it must include the courage to let bad ideas fail in public, without handcuffs.

* Khoo Ying Hooi, PhD is an associate professor at Universiti Malaya.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.