JANUARY 9 — The newly published map showing Greenland’s rare earth mineral deposits against the rest of the world has done more than inform scientists and industry watchers — it has rocked the geopolitical chessboard.

According to United States Geological Survey data, Greenland possesses some of the largest untapped reserves of rare earth elements (REEs) — those indispensable metals that make electric vehicles, smartphones, wind turbines and advanced defence systems possible.

On a global scale, China still holds the lion’s share of REE reserves at around 44 million tonnes, but Greenland’s estimated 1.5 million tonnes places it on par with or ahead of many Western producers, from Canada to much of Europe.

Rare earth minerals are more than commodities.

They are strategic assets — the backbone of the energy transition and the frontier technologies that define 21st-century competition. European Union policymakers have recognised this, noting that Greenland holds a wide array of critical raw materials needed for future industries.

Yet amid this strategic rush, a singular geopolitical drama has unfolded: Greenland is “about to go red” under Donald Trump’s MAGA-era ambitions.

instagram.com

Just weeks ago, the White House confirmed that President Donald Trump is actively discussing the possibility of purchasing Greenland, citing its strategic value in countering Russian and Chinese influence in the Arctic.

While Washington insists on pursuing diplomacy, it has kept military options on the table — a move that has alarmed allies in Copenhagen, Brussels and beyond.

This is not a fringe idea. In the US Congress, legislation such as the Make Greenland Great Again Act and a proposed Red, White, and Blueland Act have been introduced to authorise the acquisition and even renaming of Greenland.

Whether these bills pass or not, the very fact they exist speaks volumes about Washington’s strategic calculus: control of Greenland’s mineral wealth is seen as central to US national security and economic sovereignty.

But US should be cautious about the Mirage. Greenland’s rare earths are concentrated in rugged, remote southern regions such as the famed Kvanefjeld deposit — mineral riches that have attracted investment from Western firms but have yet to be meaningfully developed due to infrastructure, climatic and regulatory hurdles.

To be sure, this is no quick treasure trove. The environmental costs, indigenous interests, technical barriers and financial risks are all formidable.

Yet, for Trump and parts of his administration, the allure of Greenland has transcended geology and economics — it has become ideological.

Trump’s rhetoric frames the Arctic island not merely as a source of materials, but as a symbol of American pre-eminence amid rising competition with China.

Senior US officials have openly linked Greenland’s future to broader struggles over technological supply chains and military balance — a view that chills relations with European allies who rightly insist that Greenland belongs to its people and Denmark alone.

For Asean readers, few contexts illuminate the moment like this: we are witnessing a new style of 21st-century competition, where resource diplomacy intertwines with alliance politics, and where big powers are tempted to reshape borders not through post-war treaties but through “strategic necessity.”

This is not just about rare earths — it is about the very idea of sovereignty in an age of resource rivalry.

Denmark’s prime minister has forcefully said that any attempt by another state to take over Greenland would be unacceptable — and that a forcible acquisition would undermine alliances like Nato.

Greenland’s own leaders have echoed that sentiment, insisting their future must be decided by Greenlanders themselves.

And yet, Washington’s proposals, combined with strong investor speculation — stock surges in Greenland-linked mining companies show how markets are reacting — reflect an anxiety in the US strategic community about China’s dominance in rare earth supply chains.

Asia, too, has a stake. China’s control over rare earths is a vulnerability shared by advanced economies and middle powers alike.

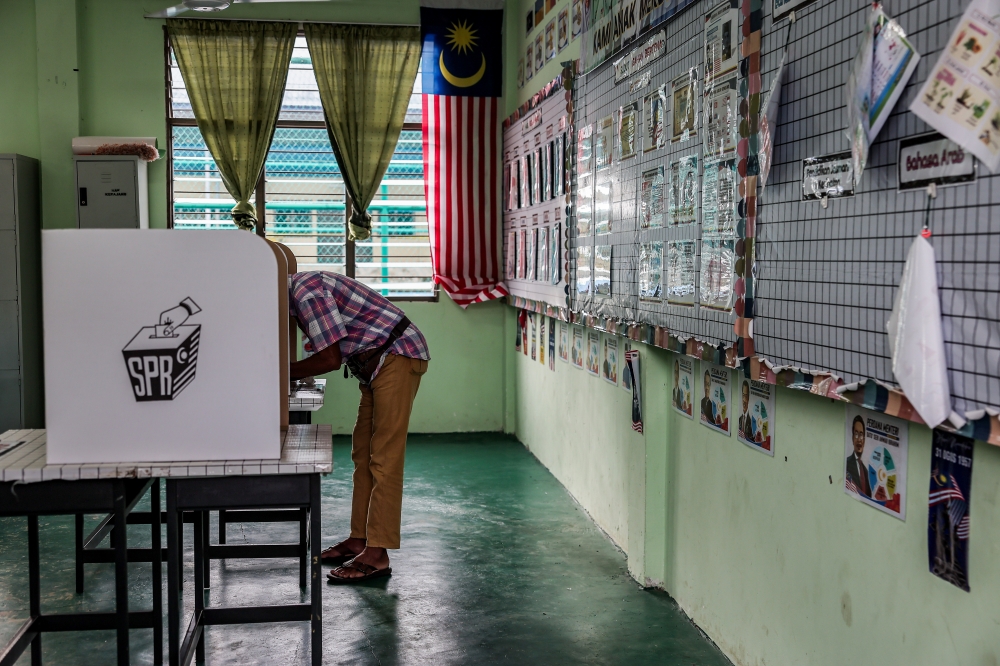

For nations such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore or Indonesia, the Greenland episode should be a wake-up call: energy and resource strategies cannot be decoupled from geopolitics.

Whether it is critical minerals in the Arctic or strategic metals in South-east Asia, the international order is one where resources confer not just economic opportunity but political leverage.

The West must reconcile two truths: first, that diversified supply chains are essential; second, that unilateral attempts to reshape sovereignty in the name of “security” risk fracturing the very alliances upon which long-term cooperation depends.

Greenland’s minerals are valuable — but not worth a transatlantic rupture.

Asean nations watching from afar should advocate for rules-based cooperation in critical resources, respect for sovereignty and equitable partnerships — because no state should have to choose between security and sovereignty.

In an era of intense technological competition, perhaps the greatest rare earth of all is trust among nations.

If that melts away like Arctic ice, the world that emerges will be far more brittle than the minerals buried beneath Greenland’s frozen soil.

*Phar Kim Beng is professor of Asean Studies at the International Islamic University of Malaysia and a director of the Institute of International and Asean Studies.

**This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.