DECEMBER 5 — For decades, Malaysia has aspired to transform from a manufacturing hub into a knowledge-driven, innovation-led economy. We have invested in gleaming science parks, established numerous public universities and research institutes, and produced a steady stream of graduates in STEM fields. Yet, a persistent question lingers: why has this considerable investment so often failed to translate into the tangible economic impact and societal advancements we crave? A recent roundtable initiated by the PTD Alumni attracted much discussion on the state of the public service in the country. And would do well if transformed.

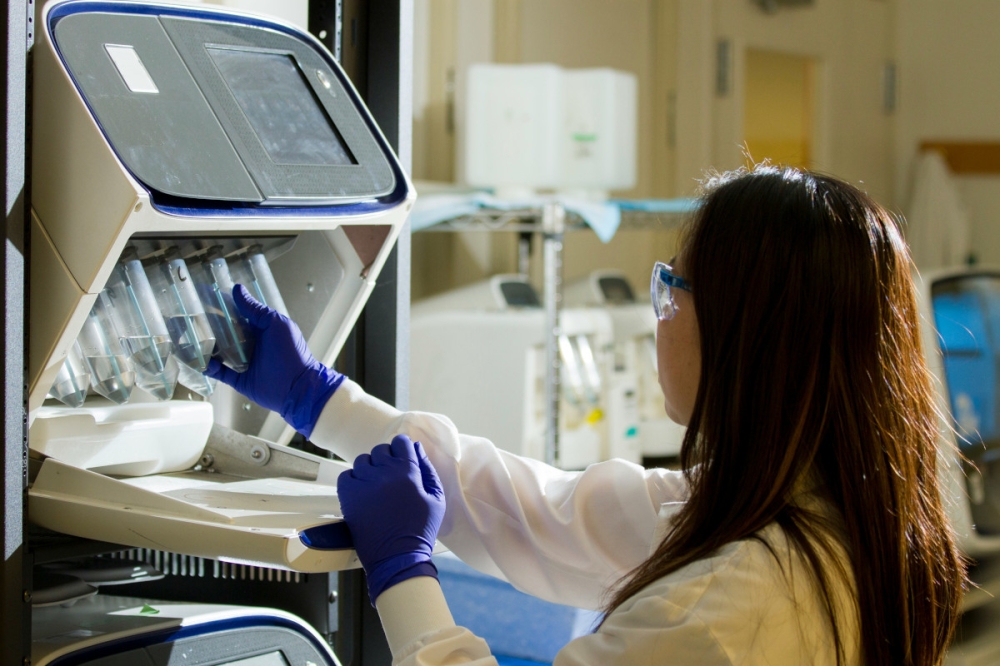

The issue of R&D came up for mention. The diagnosis is not a lack of talent or ambition, but a fractured ecosystem. Our research and development (R&D) efforts often operate in silos, trapped in a “valley of death” where brilliant ideas from laboratories never reach the commercial market. To bridge this chasm, we must move beyond merely funding research and deliberately architect an ecosystem that is mission-driven, industry-obsessed, and ruthlessly focused on outcomes. A truly effective R&D ecosystem is not a collection of independent parts, but a synergistic network. Malaysia should build upon the right pillars to invigorate a robust ecosystem.

Much of our public R&D is geared towards academic publications — a valuable currency for career advancement, but often disconnected from national needs. We must pivot to a “mission-oriented” approach. Instead of asking researchers to simply pursue their interests, the government, in close consultation with industry, should define clear, grand challenges: “Achieve net-zero energy for SMEs by 2035,” “Become a global leader in halal pharmaceutical standards,” or “Revolutionise urban farming to achieve 50% food self-sufficiency.” This focuses intellectual firepower on problems whose solutions will directly benefit the nation.

The private sector must be woven into the fabric of R&D from the very beginning. The current model, where academia researches first and then hopes to find an industry partner, is backwards. We need to foster deeper collaboration through: Mandating industry partnerships may do the trick: A significant portion of public research grants, especially for applied sciences, should require a letter of commitment from an industry partner who will co-fund and guide the project.

Provide small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with government-funded vouchers to “purchase” R&D expertise from public universities, lowering the barrier for engagement. And encourage sabbaticals for professors in companies and for industry experts to teach and co-supervise students in universities. This cross-pollination of ideas is invaluable.

The government’s role must evolve from a passive funder to an active “venture builder.” This means creating pathways for ideas to become businesses. One idea is to use stage-gated funding: Instead of a large upfront grant, provide funding in stages tied to specific commercial milestones (prototype development, securing a first customer, achieving a certain revenue target). This instils financial discipline and market awareness. We have labs for discovery, but we lack nationally accessible, affordable facilities for pilot production and scaling. Investing in shared “maker labs” and pilot plants is crucial to de-risking the journey from prototype to product. And simplify the often-byzantine process of IP ownership and licensing. Establish clear, standardised frameworks for universities and researchers that incentivise commercialisation while protecting their rights.

Our education and workplace cultures often prioritise conformity over creative problem-solving. We must celebrate intelligent failure: Not every R&D project will succeed. We need to destigmatise failure as a learning step, not a career-ender. This encourages the high-risk, high-reward research that leads to breakthroughs. And incentivise mobility: Create attractive career paths for researchers outside of academia. A researcher should be able to move seamlessly between a university, a government lab, and a corporate R&D centre without penalty, bringing diverse experiences with them.

Building this ecosystem requires a “grand bargain” between all stakeholders. The government must provide strategic direction and patient capital. Academia must embrace impact and collaboration with industry as key performance indicators, alongside publications. Industry must invest its resources and market knowledge proactively, viewing R&D not as a cost but as the bedrock of future competitiveness. The pieces of the puzzle are all here in Malaysia. We have the brains, the infrastructure, and the desire.

What we need now is the deliberate will to connect them into a coherent, dynamic, and purposeful whole. It is time to shift our focus from the number of papers published to the number of problems solved, companies created, and industries transformed. Only then will our investments in R&D truly deliver the Malaysia we envision.

*The author is affiliated with the Tan Sri Omar Centre for STI Policy Studies at UCSI University and is an Adjunct Professor at the Ungku Aziz Centre for Development Studies, Universiti Malaya. He can be reached at [email protected]

**This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.