SEPT 3 — As a Malaysian mathematics lecturer currently teaching in China, I have had the unique opportunity to observe firsthand how Chinese students approach learning mathematics. What I have discovered may surprise many back home: memorisation still plays a dominant role in their mathematical learning — and it works remarkably well.

In an age where most countries, including Malaysia, are moving towards cultivating higher-order thinking skills (HOTS) and KBAT-style (Kemahiran Berfikir Aras Tinggi) questions, China continues to place great value on rote learning, repetition, and mastery through memorisation. While this method may sound old-fashioned or rigid to some, my experience suggests that, when done correctly, memorisation can lay a strong foundation that supports, rather than hinders, critical thinking.

Inside the Chinese mathematics classroom

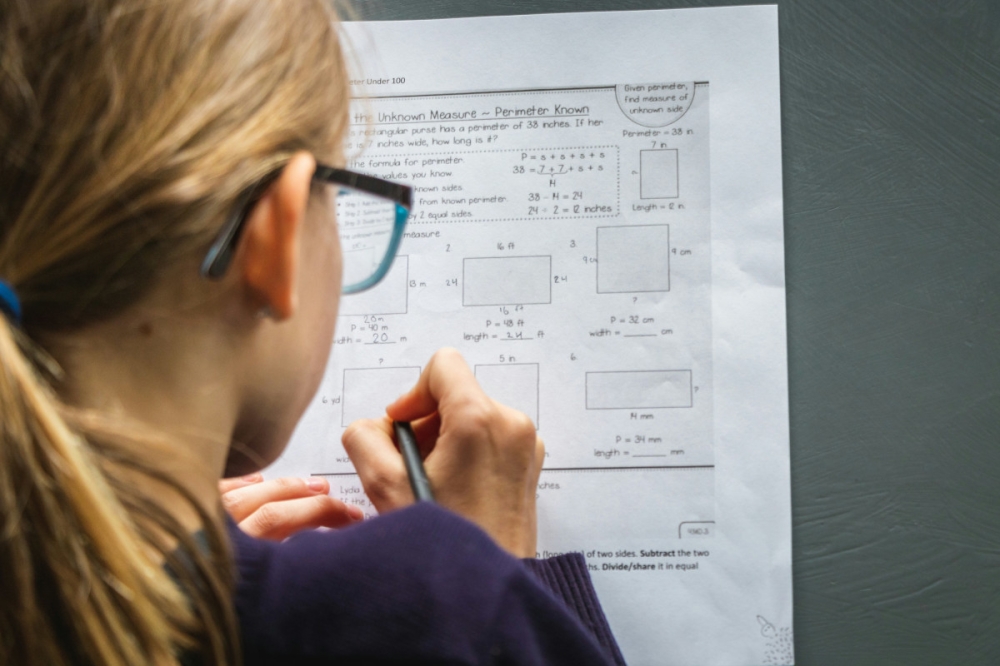

Chinese students are introduced to mathematics very early in life. Many begin memorising multiplication tables even before entering primary school. As they progress, they spend hours each day practising equations, formulas, and standard problem-solving techniques. Repetition is not just encouraged — it is expected.

In the classroom, mathematics lessons often involve reciting formulas aloud, solving dozens of practice questions in a single session, and learning worked examples by heart. Students are trained to memorise first, then understand, and finally apply. This systematic, layered approach builds both speed and accuracy — essential skills in timed assessments.

From my observation, students are not discouraged from asking questions or exploring new ideas. But they are taught that true mastery begins with knowing the basics inside out. Only when those fundamentals are solid can higher-level reasoning follow naturally.

Why memorisation works in China

There are a few reasons why this method continues to be successful in the Chinese education system. Firstly, cultural values play a role. Influenced by Confucian ideals, the Chinese education system views effort, discipline, and respect for teachers as central to learning. Memorisation is seen not as mindless copying, but as a sign of diligence and respect for knowledge.

Secondly, the examination system in China is extremely competitive and high-stakes, especially the Gaokao, which determines university placement. To succeed, students must solve complex problems under time pressure. In this context, having formulas and problem-solving steps committed to memory provides a significant advantage.

More importantly, memorisation in China is not a substitute for understanding — it is the path to it. Once students have memorised formulas and methods, they are trained to recognise patterns, apply their knowledge to new contexts, and think critically under exam conditions.

In fact, Chinese students consistently score at the top of international assessments such as PISA, which test real-world mathematical reasoning, not just memory recall.

But what about HOTS and KBAT in Malaysia?

Malaysia’s education system, especially in mathematics, has evolved significantly over the years. With the emphasis on HOTS and KBAT, students are expected to go beyond remembering formulas; they must analyse, apply, and evaluate mathematical concepts in unfamiliar scenarios.

This is a commendable direction. However, during my time teaching in Malaysia, I often observed that students struggled with HOTS questions not because they couldn’t think critically, but because they lacked confidence in basic skills.

Many couldn’t recall important formulas or standard procedures, making it difficult to even begin solving a higher-order question. This is where I believe we can learn from the Chinese approach. Memorisation, if used wisely, can be the stepping stone to critical thinking — not the opposite of it.

A balanced path forward

Malaysia doesn’t need to return to full rote learning, but it should find a balanced approach that combines memorisation with critical thinking. Students can first master basic formulas and procedures through repetition, especially in the early years, and then apply them to real-world and KBAT-style questions to deepen understanding.

Using a spiral learning method — where previously learned concepts are revisited and applied in more complex ways — helps reinforce knowledge over time. Assessments should value both accuracy and reasoning. Teachers can support this balance by starting lessons with simple drills and ending with discussions or problem-solving tasks, helping students become both confident in facts and flexible in thinking.

My time in China has shown me that memorisation, far from being outdated, can be a powerful learning tool when combined with deeper understanding. Chinese students excel in mathematics not just because they memorise, but because they build fluency first, then use that fluency to tackle complex problems.

HOTS and KBAT are essential, but they must stand on a firm base. Memorisation, when used purposefully, can help build that base — giving our students the confidence and competence to excel both in exams and in life.

* Danitah Selainerthi is a Lecturer at the Mathematics Department, Centre for Foundation in Science (Pasum), Universiti Malaya and may be reached at [email protected]

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.