NEW YORK, May 22 ― Among the books, periodicals and letters found in Osama bin Laden’s hide-out in Pakistan was a copy of former CIA officer Michael Scheuer’s 2004 book, Imperial Hubris: Why the West Is Losing the War on Terror, which describes the al-Qaeda founder as “the most respected, loved, romantic, charismatic and perhaps able figure in the last 150 years of Islamic history.”

Also in his library was a copy of Michel Chossudovsky’s conspiracy-minded book America’s ‘War on Terrorism’, which argued the September 11, 2001, attacks were simply a pretext for American incursions into the Middle East, and that Osama was nothing but a boogeyman created by the United States.

These books and others, along with dozens of journal articles and magazine clippings, were found when a Navy SEAL team raided Osama’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011. Declassified on Wednesday, they highlight the al-Qaeda leader’s fascination with the West. They also illustrate the efforts he made to understand America (the better to fight it) and his need to confirm his own beliefs about its rapacity and corruption (perhaps to justify his terrorist attacks).

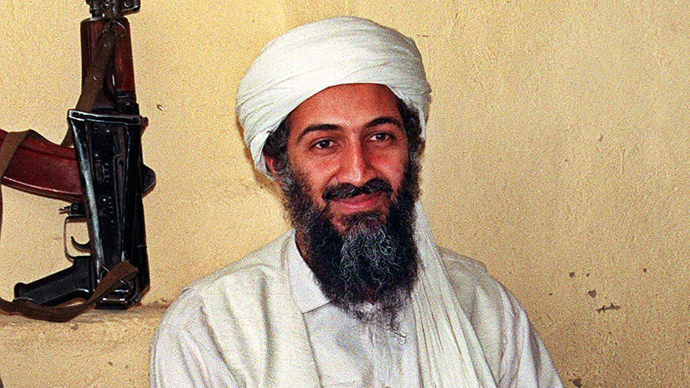

It should not come as a surprise that the terrorist leader was concerned with his legacy and world image ― after all, he was famously recorded watching video of himself on television. Holed up in Abbottabad for perhaps as long as five years without an Internet connection, Osama had plenty of time to read about himself, al-Qaeda and his enemy, the United States.

Osama learned English at an elite Western-style high school in Jiddah, Saudi Arabia, where he was by most accounts a serious, sober student, and his library suggests that he spent his last years in hiding as a student again ― but a student of terrorism, fixated on US imperialism.

The declassified list released by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence includes art books (Arabic Calligraphy Workshop) and health books (Grappler’s Guide to Sports Nutrition) described as “documents probably used by other compound residents.” Osama’s books, however, appear pretty much work-related ― little or no recreational reading, it seems, for the al-Qaeda leader.

Some of the books are mainstream history or journalism: Obama’s Wars by Bob Woodward; The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers by Paul Kennedy; and The United States and Vietnam 1787-1941 by Robert Hopkins Miller. Others are conspiracy-mongering tomes like Bloodlines of the Illuminati by Fritz Springmeier; The Taking of America, 1-2-3 by Richard Sprague; and Secrets of the Federal Reserve by Eustace Mullins, a Holocaust denier.

There are two works by Osama’s early mentor, Abdullah Azzam (The Defense of Muslim Lands and Join the Caravan), about jihad.

There is also a sizable cache of documents relating to France, such as Wage Inequality in France and France on Radioactive Waste Management, 2008. And there are books by left-wing writers Greg Palast (The Best Democracy Money Can Buy) and Noam Chomsky (Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance) that Osama probably thought ratified some of his own views about US imperial ambitions and corporate corruption.

While stuck in Abbottabad, Osama seems to have been studying publicly available US government documents and articles and radical publications. He also read Foreign Policy magazine articles and RAND Corp studies on counterinsurgency, trying to keep a handle on the war on terrorism he had set off.

His bookshelf is a weird hodgepodge. It’s hard to know how complete a list it is, and whether he requested certain books from aides, or if aides sent him works they thought he might like or that might influence his thinking.

The declassified letters and correspondence reflect Osama’s managerial concerns ― al-Qaeda had become a kind of giant corporation. His self-prescribed syllabus included works on global issues, like climate change, and ran a spectrum from historical works to crackpot conspiracy tracts.

The eclectic nature of the list speaks to both Osama’s reach as al-Qaeda’s leader and his limitations as an international fugitive; his ambitions to think globally and his naive susceptibility to theorists who talk conspiracy to explain the perfidies of the West; his fascination with America and his determination to find new ways to attack it by trying to understand the dynamics of its political and economic systems.

As Steve Coll wrote in his compelling biography of the bin Laden family, The Bin Ladens: An Arabian Family in the American Century: “Osama was not a stranger to the West,” having grown up in one of Saudi Arabia’s wealthiest families and traveled abroad, “but by age 15, he had already erected a wall against their allures. He felt implicated by the West, and by its presence in his own family, and yet, as he would demonstrate in the years ahead, he lacked a sophisticated or subtle understanding of Western society and history. He used his passport, but he never really left home.” ― The New York Times