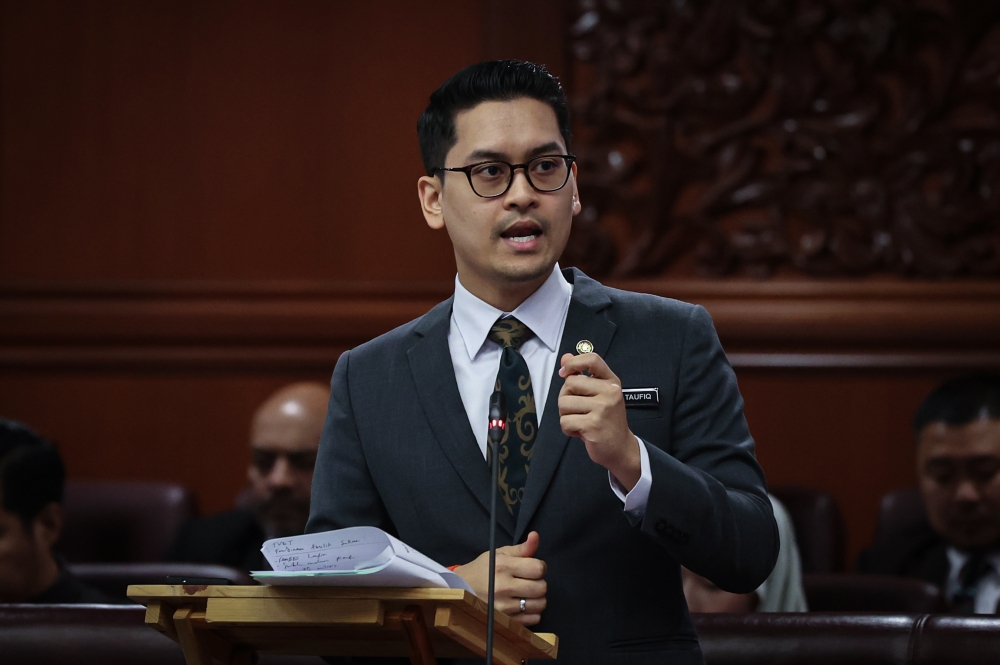

JULY 11 — A few days after the federal territories minister issued his ban on soup kitchens within a 2km radius from Lot 10, I joined the children of Yayasan Chow Kit for buka puasa on my birthday.

I have been a Trustee since its inception, and was involved while it was still operating as Rumah Nur Salam under the auspices of Yayasan Salam Malaysia. Today YCK operates three centres: Pusat Jagaan Baitu’Amal and Pusat Aktiviti Kanak-Kanak (PAKK) for younger children and the KL Krash Pad (KLKP) for teenagers. Over the years hundreds of children have regularly used the various services provided by the centres — including shelter, education, counselling and rehabilitation — funded by a combination of government grants and corporate donations.

![]() Many of the children of Yayasan Chow Kit are stateless or refugees, and encounter particular difficulties in accessing services, especially education. We have long argued that it is in everyone’s interests that these children are in school instead of on the streets – where unfortunately they can end up being involved in activities that incur social costs – but the standard response from policymakers is that non-Malaysians should not receive services paid for by Malaysians. “Publicly-funded Malaysian schools are for Malaysian children,” some parents will no doubt insist, “and I don’t want my kids sitting with refugees.”

Many of the children of Yayasan Chow Kit are stateless or refugees, and encounter particular difficulties in accessing services, especially education. We have long argued that it is in everyone’s interests that these children are in school instead of on the streets – where unfortunately they can end up being involved in activities that incur social costs – but the standard response from policymakers is that non-Malaysians should not receive services paid for by Malaysians. “Publicly-funded Malaysian schools are for Malaysian children,” some parents will no doubt insist, “and I don’t want my kids sitting with refugees.”

That is why Ideas, in partnership with the Dutch NGO Young Refugee Cause, is establishing a learning centre, the Ideas Academy (www.ideasacademy.org.my), to cater for needy urban children including the stateless (this is separate from our other educational initiative, the Ideas Autism Centre). It will use the Canadian curriculum bearing in mind that many of the students may ultimately be destined for other countries, and hopefully prove beyond doubt that civil society can work effectively with the private sector to provide educational services to the most disadvantaged in society — a notion that is equally incomprehensible to the authoritarian Right as to the socialist Left, who believe that government must monopolise the education sector to ensure “proper values” or “justice for all” (how’s that working out, eh?).

While there are such initiatives for children, however, there are also thousands of adults who are homeless in Kuala Lumpur. As has already been related in many stories since the debacle started, these encompass a mix of people: from those who have long been living on the streets engaging in petty trade, to those who once had relatively comfortable lives but later encountered personal tragedies, deaths in the family or other misfortunes. It is to these people that soup kitchens have catered.

Soup kitchens are perhaps the ultimate symbol of civic responsibility: their funders and volunteers understand the frailties of urban life and dedicate financial resources as well as time to help those who have been its victims. But there is one aspect which trumps them all: from my observations and interactions with soup kitchen volunteers — whether here, in London or in the most impoverished parts of Detroit which I visited last year — one consistent characteristic is the dignity with which people are treated. Unlike impersonal government welfare programmes designed on the basis of statistics and maps and potential political capital, soup kitchen volunteers interact with individuals face-to-face, immerse themselves in the community and ultimately earn respect, friendship and gratitude.

Perhaps we are all being too harsh on the federal territories minister. Our capital would indeed look smarter if there were no visible signs of poverty. And our tourist spots are indeed blighted by syndicates of beggars, not advertised in the Visit Malaysia Year 2014 brochures. And some of these syndicates are indeed foreign. But the one-handedness with which the new measures were announced points to a breath-taking ignorance on the part of the authorities by putting everyone in the same boat. As we have seen all too often in pronouncements of government policy, there was little prior consultation with those who are most well-versed in the topic.

I would reiterate another point about governance: it is high time that our cities are governed not by appointees of Putrajaya or state governments, but instead be given the right to directly elect executive mayors with significant responsibilities. This would create much greater local accountability on all issues directly affecting the cities.

Some politicians would find such a development intolerable to their career prospects: to them I say emulate Joko Widodo, who proved himself as mayor of Surakarta before running as governor of Jakarta, and now he is a presidential candidate.

After the federal territories minister made his announcement, one soup kitchen which operates within the banned zone approached YCK to see if we could host them. Our centres are just outside the zone, so if we can, we will!

*This is the personal opinion of the columnist