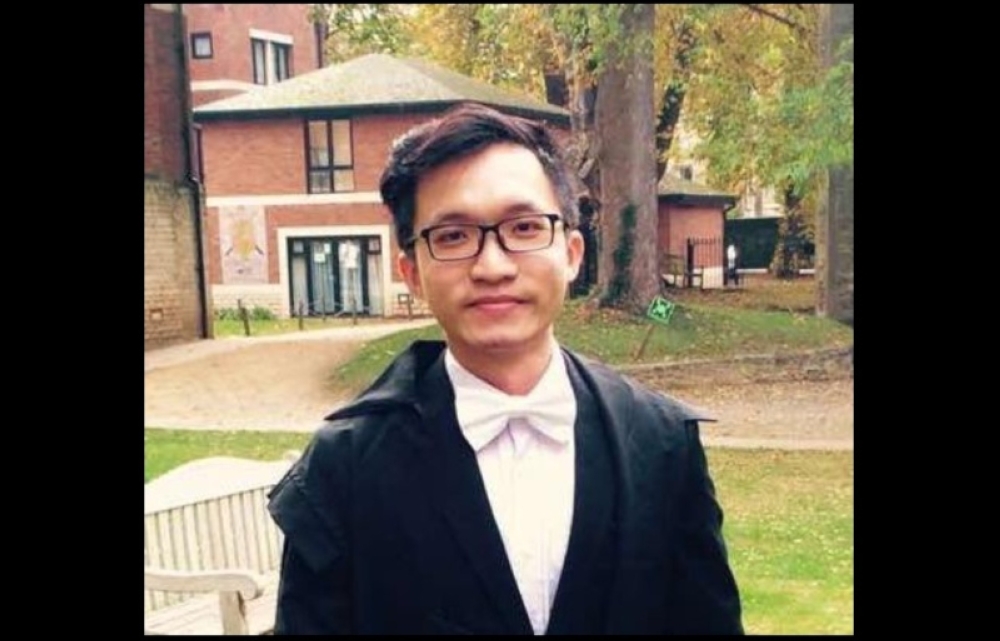

KUALA LUMPUR, April 5 — The High Court today declared that 24-year-old Nalvin Dhillon — who was born to a Malaysian father and Filipino mother — a Malaysian citizen under the country’s Federal Constitution as he was not born a citizen of any other country, finally putting an end to years of being stateless.

Nalvin, who is due to turn 25 in June, had been trying together with his biological father since December 2009 or slightly more than 13 years ago to have himself recognised as Malaysian.

The decision was delivered by High Court judge Datuk Wan Ahmad Farid Wan Salleh to recognise the boy from Klang as Malaysian.

“The plaintiff has fulfilled the condition precedents of Section 1(e) of Part II of the Second Schedule of the Federal Constitution. Once this is established, the law is that citizenship by operation of law is almost automatic. It is a matter of birthright.

“For the aforesaid reasons, I am making a declaration that the plaintiff is a Malaysian citizen by operation of law under Article 14(1)(b) of the FC read together with Section 1(e) of Part II of the Second Schedule of the FC.

“As a consequential order, the defendants are directed to issue a MyKad to the plaintiff within 21 days from the date of this order,” Wan Ahmad Farid said while delivering his decision through video-conferencing.

The Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b) provides that every person born on or after Malaysia Day and fulfilling any of the conditions in Part II of the Second Schedule is a citizen by operation of law — or automatically entitled under the law to Malaysian citizenship.

Section 1(e) is the condition where the person born within Malaysia is not born a citizen of any country.

Nalvin was represented by lawyer Larissa Ann Louis, while the three respondents were represented by senior federal counsel Nik Isfahanie Tasnim.

Lawyers Low Wei Loke and Mansoor Saat held a watching brief for the Malaysian Bar and the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia respectively.

What happened in this case

Based on court documents, Nalvin was born on June 5, 1997 at a public medical facility in Klang, Selangor to a Malaysian father and a Filipino mother.

His birth was officially registered on July 25, 2001 with a birth certificate subsequently issued.

Since Nalvin’s birth was registered four years after he was born, his birth was made under late registration pursuant to Section 12 of the Birth and Death Registration Act (Act 299) by the National Registration Department (NRD) at the material time.

According to the NRD, there was an absence of both a valid marriage record and registration between Nalvin’s biological parents at the time of his birth; thus, he was considered an illegitimate child in accordance with Section 13 of the BDRA.

Based on Nalvin’s affidavit, his biological mother left the family when he was four years old in 2001, and despite the numerous attempts by both father and son, they have been unable to locate her whereabouts as of today.

In the same year, Nalvin’s father successfully applied for a Malaysian passport for Nalvin and he was granted Malaysian citizenship status in his new travel document which he used to travel to Australia.

Fast forward to 2009, and Nalvin’s father made an attempt to have his son obtain his Malaysian identification card (MyKad) when he turned 12.

Instead, it was discovered that Nalvin’s birth certificate extracted from the NRD’s database had explicitly listed him as a ‘Bukan Warganegara’ or non-Malaysian.

Subsequent to their discovery, Nalvin’s father had made several attempts to have his son recognised as a Malaysian and obtain a birth certificate stating as such over a period of some seven years.

He had submitted a total of three citizenship applications — December 31, 2009, November 29, 2012 and June 11, 2014 — under Article 15A of the Federal Constitution.

However, the Home Minister through three letters – dated December 8, 2010, January 20, 2014 and April 4, 2016 — rejected their applications without giving any reason.

By the time he received the ministry’s response on his third citizenship application, Nalvin was already aged 19.

Article 15A provides that the federal government may register anyone under the age of 21 as a Malaysian citizen, “in such special circumstances as it thinks fit”.

On September 6, 2019, Nalvin filed a lawsuit via an originating summons against three respondents, namely the National Registration director-general, the Home Ministry’s secretary-general and the Malaysian government.

In his lawsuit, Nalvin sought orders from the court for declaration to recognise him as a Malaysian citizen pursuant to operation of law under Article 14(1)(b) and/or Article 18 of the Federal Constitution, as well as a similar citizenship declaration under Article 19.

Nalvin is also seeking to have the named respondents issued both a birth certificate and MyKad which reflects his Malaysian citizenship within 21 days from the date of the court’s order.

In his written affidavit, Nalvin said he had faced difficulties enrolling in a tertiary education institution and obtaining a driver’s licence, as well as had been unable to open a bank account or conduct any form of online transaction because he did not possess a MyKad.

He also said his biological father is a Malaysian patriot who served his country in the Royal Malaysian Air Force with a recorded 22 years of service.

Based on court documents, one of the main arguments by Nalvin’s lawyers was that the Malaysian government has implicitly recognised him as a Malaysian citizen by way of issuing a valid passport and thus had a legitimate expectation to be treated as such.

Asserting that a Malaysian passport is only exclusively issued to its citizens by the government, they submitted that said official document entitles its holder to travel under its protection to and from foreign countries as stipulated under Section 1A of the Passports Act.

They also argued that the defendants’ claim that they have no connection or were unaware of Nalvin’s status was unacceptable as these government agencies were required to work together.

Based on court documents, the defendants had argued that the principle of legitimate expectation is not applicable in the instant case despite being an acceptable principle in Malaysia.

They said the representation cannot be relied on to say citizenship is acquired automatically without fulfilling the requirements by way of operation of law under Article 14(1)(b) read together with Section 1 Part II of the Second Schedule of the FC.

In his grounds of judgment, Wan Ahmad Farid said he found it difficult to comprehend when it was argued that the issuance of a Malaysian passport did not constitute the granting of a citizenship.

The basis of the arguments, the High Court judge said, was because both official documents had been issued by two different government agencies, albeit under the same Home Ministry.

“With respect, I find this difficult to comprehend. I say this for three reasons.

“First, both the Immigration Department and NRD are within the purview of the second defendant (Home Ministry). That the two departments within the same ministry cannot coordinate with each other is something beyond me.

“Secondly, there is no evidence before this court that the passport issued to the plaintiff was revoked by the Immigration Department at the insistence of the NRD.

“Thirdly, the fact that the plaintiff issued a Malaysian passport raises the presumption that he is a Malaysian citizen,” Wan Ahmad Farid said.

Wan Ahmad Farid noted that once the plaintiff had shown to the court he was issued a Malaysian passport, he had established that he was not born a citizen of any other country.

“Unfortunately, except for saying that the passport was not issued by the NRD, the defendants have failed to rebut this presumption,” he added.

Following the High Court’s decision, another of Nalvin’s counsels Annou Xavier told Malay Mail he hoped the Malaysian government would issue a MyKad to his client without further delay.