KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 5 — Did the recent massive floods in Selangor and other parts of the country leave you wondering how such widespread and heavy damage could have been reduced?

Malay Mail spoke to two disaster management experts who listed various things Malaysia needs to improve on, including harnessing real-time data, tapping into the wisdom of local residents and locally-based agencies in the disaster-prone or disaster-hit area itself, and investing to reduce the impact from floods itself.

Here’s a checklist of what can be done:

1. Better coordination

Universiti Sains Malaysia researcher Khairilmizal Samsudin noted that Malaysia’s various agencies are capable in terms of tactical work or the actual on-site response involving the use of assets such as boats, evacuation and search and rescue operations.

However, the challenge is in having a “unified command” when coordinating a response from multiple agencies.

Khairilmizal stressed that the federal government should only be dealing with the strategic aspect of disaster response, such as arranging which areas to deploy resources to and to determine areas that really need support as well as to ensure that aid is distributed properly and in a balanced manner.

“The same thing happened during the 2014/2015 nationwide floods, the federal government needs to concentrate on the strategic part of managing the disaster and stop micro-managing lead responding agencies and taking over their ‘tactical’ on-site operations,” he told Malay Mail.

Under Malaysia’s current disaster management structure which involves disaster management committees at the district, state and federal level, the state-level committee is to step in when the district-level committee is unable to handle the disaster on their own, while the federal government steps in to assist when the state government needs help with managing the disaster.

“The federal government’s agencies don’t have enough info -- what is the exact location that is prone to or majorly impacted during disasters. So when the federal government came in and… mobilised resources to the impacted area without consulting the local responders or local experts, this is where certain areas didn’t get enough support and other areas got more support,” the lecturer at USM’s School of Health Sciences’ Environmental and Occupational Health Programme noted.

Noting the announcement for non-government organisations to register with the National Disaster Management Agency (Nadma) in order to carry out rescue and relief work in Selangor during the recent floods, Khairilmizal questioned the need to report to the federal government when the Social Welfare Department (JKM) would have the data on those who need help.

“Why do NGOs need to go to the federal first and then come back down to the municipality? Why don’t they just go to the nearest police station or the local responding agency to assist the local community, to ask where they should be deployed? It will be much faster, that is the best way to respond and manage these kinds of situations,” he said.

“It should be centralised but it shouldn’t be micromanaged. If we look at the National Security Council Directive No. 20, it is clearly stated that the district will lead the response at district level; at state level, the state will lead the response at state level; but when they need more assistance because they don’t have power, resources, financial support, this is where federal government should come in and support, but still federal government should not interfere with tactical strategy. The one leading tactical response should still be state and district emergency responders because they know the area.”

On December 20, both Nadma and the Fire and Rescue Department asked volunteers to register to enable the authorities to keep track of them to ensure their safety during the flood rescue and relief efforts.

Khairilmizal said the Selangor floods showed that much effort is needed to improve the five elements of effective emergency management, namely effective command structures, comprehensive information management, good situational awareness such as having a system for real-time information on the status of help needed in an area to enable effective coordination of aid and rescue efforts, capable communication matrix, and adequate resource and logistics.

2. Clear chain of command during large-scale disasters

Khamarrul Azahari Razak, director of Universiti Teknologi Malaysia’s Disaster Preparedness and Prevention Center (DPPC), said that learning from the past is key to better predict the future and be better prepared for the worst case scenario.

Among items that he listed as needing substantial improvement are command and control, multi-tier risk communication, targeted disaster relief, large-scale disaster response and local disaster risk reduction capacities.

He highlighted that responding to a large-scale disaster is not solely the responsibility of emergency responders and government agencies, but noted that community leaders and the grassroots also have a role to play and contribute during such calamities.

In terms of command and control for example, he said Nadma’s role under the NSC Directive No. 20 is only to help the state when the floods exceed the state’s response capacity, noting: “But they can’t really take over the command and control, because it was delegated to the state, you can’t really have two commanders at one particular mission.”

He suggested reviewing the current guidelines and policy documents to clarify the chain of command during large-scale disasters.

He pointed out that Selangor had successfully handled various disasters that happen annually such as forest fires, peat fires, coastal flooding, but that those disasters were not at a large scale such as the December 2021 floods.

3. Informing public of danger, keeping communications alive

As for multi-tier communications, Khamarrul noted that there cannot be a break in the communications of disaster risks — when a flood situation is being communicated between federal and state governments and the districts or between government agencies, or when the district office informs the local community organisations like Village Community Management Councils (MPKK) and Village Development and Security Committees (JKKK) and which should then alert the local communities in their area.

“So if you send a message at 2am, it must be properly received at the local level,” he said, noting the need to prepare a list of actions in advance for such a scenario and the establishing of platforms or tools to communicate and pass along orders.

He said the need to provide backup for communication during disasters between the local communities, district offices and state disaster operations command centre, such as for situations where social media app WhatsApp cannot be relied on when electricity supply is cut off and mobile phone batteries are dying.

At Hulu Langat in Selangor which Khamarrul had visited during the floods, he noted for example that the Malaysian Amateur Radio Transmitters’ Society had briefly stepped in to help re-establish communications in the area when there was no electricity and the usual mobile networks were down.

There should also be steps taken for “improving the risk communication at a local level, disseminating the risk information to the vulnerable communities, and improving the capacities and communication between non-government organisations and civil society organisations.”

He said there should also be a communication platform connecting the government to the private sector such as corporate donors and to the civil society who may wish to contribute money or aid items but are unsure how many are affected, adding that there must be effective communication between non-government organisations as well to avoid wastage of resources.

For example, he noted that those in Hulu Langat had been forced to throw away food as volunteers had sent cooked food even at 10pm and as new food comes in the next day for breakfast, and that waste management then became an issue.

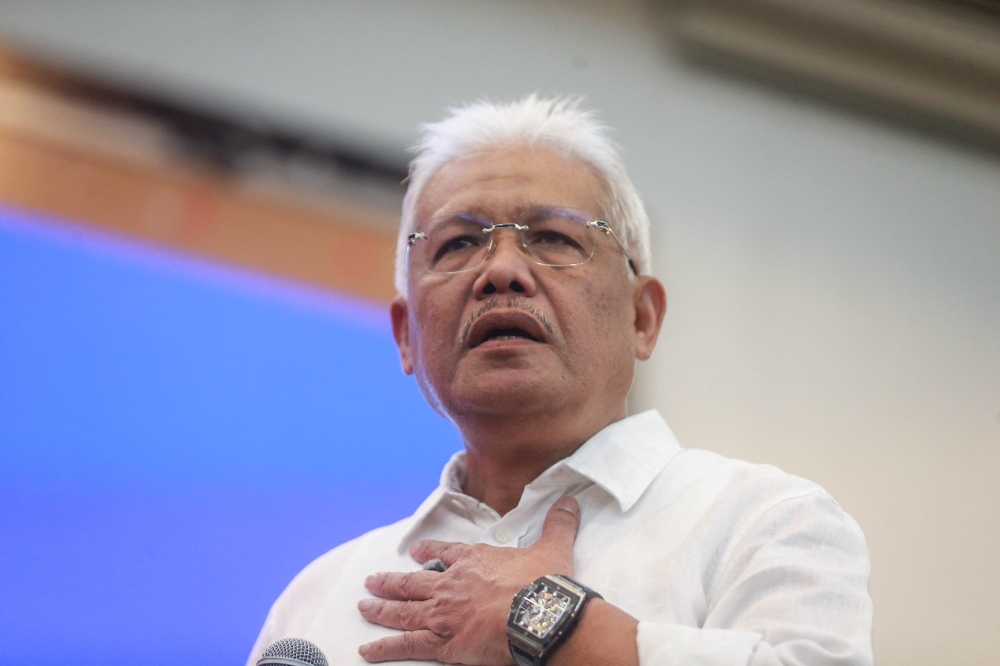

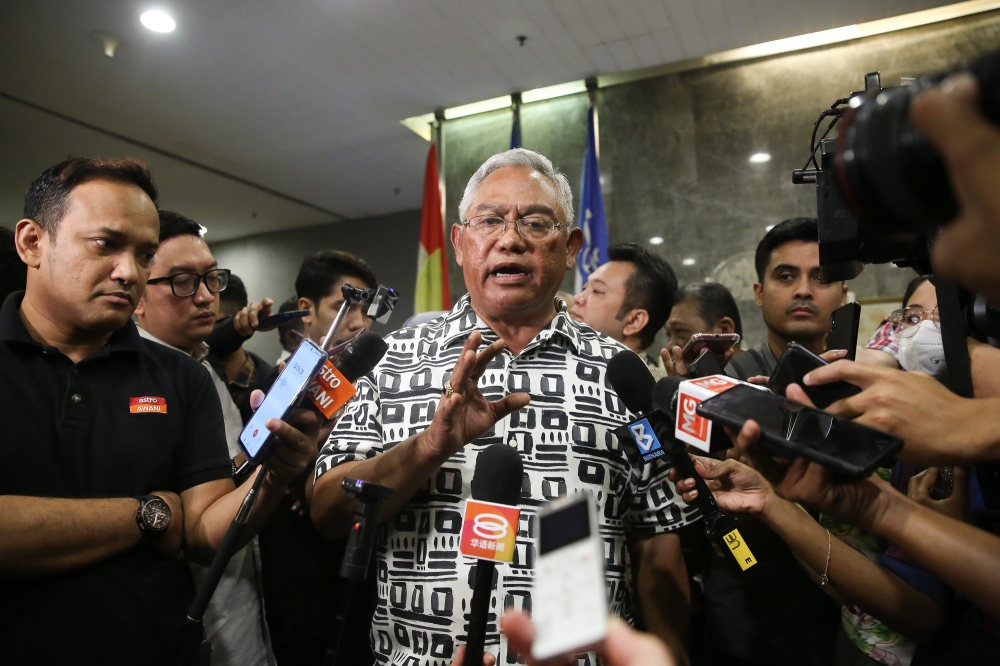

On January 2, Communications and Multimedia Minister Tan Sri Annuar Musa was reported suggesting that telecommunication towers in flood-prone areas be built on higher platforms of around three metres to prevent communications from being cut off and to enable flood victims to send out calls for help even when stranded on rooftops, while also urging for a better system to give early warnings to the public of impending disasters.

The minister had cited the example of Japan where earthquake alerts would be sent to every mobile phone user.

The National Security Council Directive No. 20 — which outlines Malaysia’s disaster management system — states that the communications system between the rescue agencies and relief and recovery agencies are to be activated during disasters, including the use of the Government Integrated Radio Network (GIRN) by the disaster operations commander in managing the disaster on-site.

Khairilmizal explained that Malaysia’s GIRN uses a satellite communications system for interagency communication where communications can be made to multiple agencies at the same time, and that such system is not dependent on local communication towers and can operate even in remote areas or when the telephone lines are down due to electricity disruptions.

4. Using real-time data

Khamarrul suggested “exploring a trusted, high-precision and improved forecasting and impact-based early warning system particularly addressing urban disaster due to extreme weather events, and climate change.”

Instead of just having an early warning system that could warn of a flood hours or days in advance, such a system should also be “impact-based” where a flood warning could be issued with the knowledge of how many people in a specific area would be affected or impacted by the floods.

Compared to the current warnings of prolonged heavy rain in a general area like Shah Alam in Selangor, an impact-based warning system would need a good database with integration of data from multiple agencies or departments that could pinpoint the demographics at a specific apartment block that would be hit by the floods — such as how many are women or men, how many are underprivileged, how many of the residents were recently born.

“We just release the warning in advance without really knowing who is actually impacted. In the Philippines or Vietnam, they can predict this typhoon will be crossing this district and affecting 15,000 people, so to get that number they have to get proper modeling and analysis, so I think there is room for improvement in the current early warning system,” he said.

He said Malaysia’s early warning system should be enhanced to a point where the data can be easily accessed even at 2am when disaster strikes, and that more investment and more data is needed to enable such a system to provide real-time data of how many residents are living in a particular flat instead of giving out-dated data.

“So how do you invest in impact-based early warning systems if you don’t build a good database? So we need to revamp the current system and the system should also consider some of the traditional or local knowledge,” he said.

He said there may not necessarily be a need to build from scratch and technology as social media apps such as Facebook and Twitter could be used to track the number of those in disaster-affected areas, stating: “So whenever you plot all the population, you can quickly calculate how many are actually in affected zones, so you can mobilise the right number of assets, how many boats are needed, but now all these numbers are not in place, so I think we have to improve.”

5. Tapping into local wisdom

Khamarrul also suggested investing in local governments’ capacities, and the “co-designing of Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience Strategy based on real-time data, scientific modeling injected with traditional knowledge, and local needs and demands.”

He said such strategies can be designed together with the state, civil society organisations, professionals from the private sector and even with local input, noting that these strategies should result in action plans supported by real-time data and good modeling and traditional knowledge.

For example, he noted that locals living in a flood-hit area may have experienced major flooding decades ago and that wooden houses in such areas may be built at least 1.5 metres in height to adapt to the worst case scenarios while newer generations build houses in the area without considering past floods, or that locals would know the original path or channel of rivers in an area, noting: “So these kind of traditional knowledge or local knowledge should be injected into the strategy, into the action plan.”

He said such strategies should be designed to not only cover the phase during disaster, but to also aid in the post-disaster recovery process.

The grassroots’ role and shared responsibilities must be renewed and tightened, while community-led disaster drills should be held frequently under a large-scale disaster scenario based on extreme weather events.

“One of the best example, the Ampang Jaya Municipal Council (MPAJ), they have a dedicated unit for slope engineering, so when a disaster or slope failure takes place in Bukit Antarabangsa or in Ampang Jaya, this dedicated group under the local council will react quickly. That’s why I used the word decentralisation, instead of wait for orders from the top, they can handle on their own immediately or at least make an early action before the government assistance arrives,” he said when suggesting the empowering of local councils to set up their own dedicated units to handle disasters.

6. Minimising the floods’ impact

To reduce damage from floods, Khamarrul recommended investing in disaster risk reduction for societal resilience, noting that individuals can for example invest by buying flood insurance.

Another example would be funding better drainage and also proper maintenance of drains, such as paying contractors to clean up and remove rubbish from drains two months before the monsoon season.

The use of nature-based solutions should also be explored to reduce the risk of flooding as these measures are not too costly, more eco-friendly and can be led and maintained by the community and can also be part of river rehabilitation efforts.

More examples of nature-based solutions — which could include conserving and restoring mangroves — to mitigate floods can be found here in the World Wildlife Fund’s “Natural and Nature-Based Flood Management: A Green Guide”.

He also mooted mainstreaming disaster risk reduction and resilience into development-planning and control, where city planners or town planners should carry out proper zoning of land use based on information of which areas are flood-prone or could potentially be flooded in the future.

“So whenever we develop a local city plan, we have to consider a disaster area. This area has frequent flood issues, this area may not have flooding issues at the moment, but if you disturb the land use and drainage pattern, it may induce new flooding in the future,” he said when speaking of a risk-informed development strategy.

While totally disallowing any developments in areas with flood risk could be an option, he said property developers could also be allowed to develop in a disaster-prone area — if there is insufficient land for example — but should then work with city planners and incorporate disaster mitigation measures into their housing projects.

“The developers can develop the area, but they have to build better monsoon drains for example, they have to build maybe sirens, they have to build dedicated evacuation centres, they can provide some search and rescue type of equipment,” he said.

“Some developers are actually the source and the root of the problem, they just want to increase the profit but they don’t want to invest in disaster risk and reduction. To reduce risk, you have to invest,” he said.

Aside from mooting the promotion of risk-informed sustainable development, he also suggested financing local disaster risk reduction solutions and services, as well as rejuvenating a community-led and nationally-supported disaster risk reduction strategy.

To minimise the impact of floods, he also suggested promoting a science-based decision-making process for rapid, timely and accurate results, and the financing of a multi-hazard, vulnerability and risk assessment based on geospatial technology.

For geospatial technology which involves the capturing of geographical information and mapping of locations, he said this could include using satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones to map out where flood victims are located, where the evacuation centres are located and what are the safe routes.

Such geospatial information can help the search and rescue teams or the flood victims themselves, and can be used to help in handling the preparation, mitigation and recovery phase of a disaster.

.JPG)