KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 3 — If you could sum up some of the biggest moments in your life in 2020 in just a chart with numbers and facts, what would it be?

Here’s a look back at some of 2020’s most defining moments or events for Malaysia, summarised in charts and infographics that will take you on a quick scroll down memory lane. You might even see something you never noticed or somehow missed:

1. Year of Covid-19

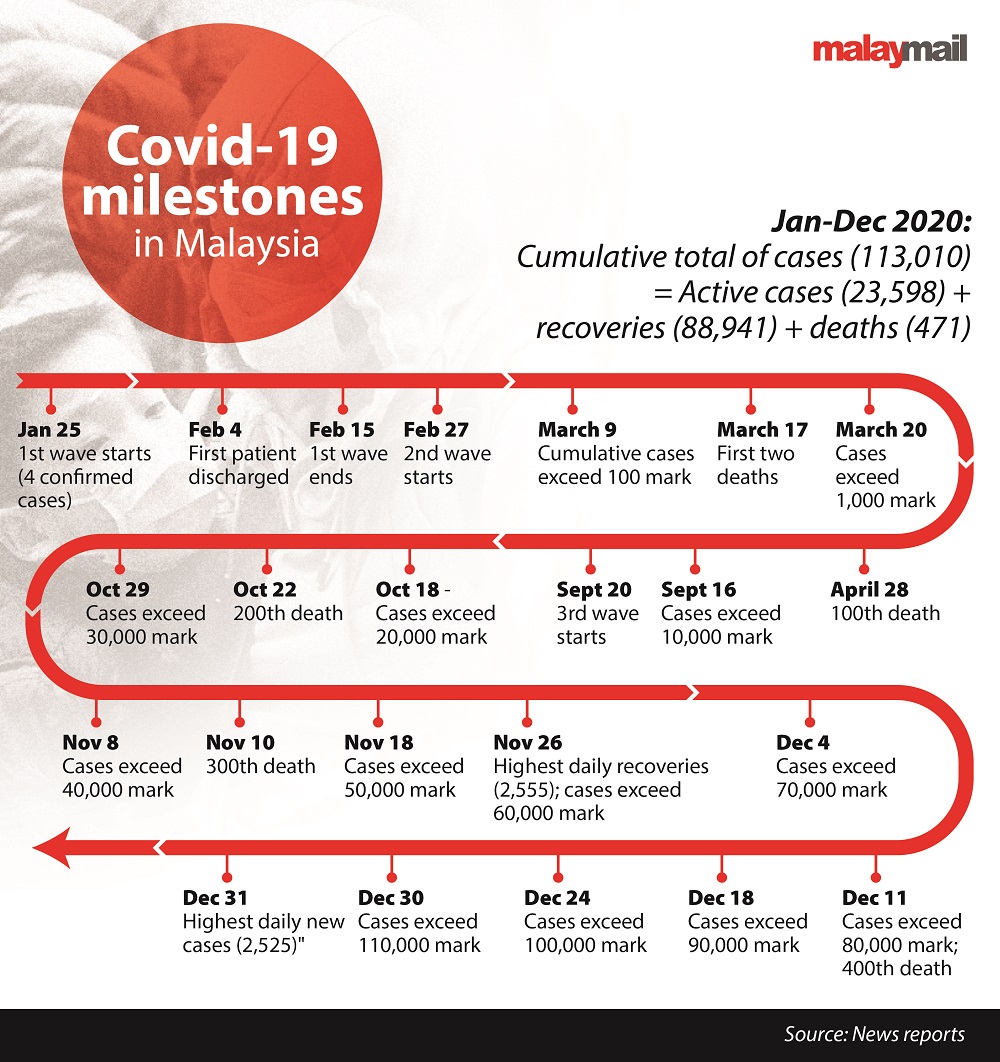

Malaysia had a gentle start to the Covid-19 pandemic with just 22 cases in the first wave from January to February, with zero cases for 11 days before a second wave of over 10,000 additional cases within the late February to mid-September period with mostly two-digit or even single digit of cases from June to September. This then escalated to an additional 100,000-odd additional cases in the third wave spanning the last four months of 2020.

It was also during the third wave that the daily number of new Covid cases detected surpassed 1,000 cases for the first time on October 24, before crossing 2,000 cases for the first time a month later on November 24.

Here are some of the reasons cited by the federal government on December 3 for the third wave spikes, apart from the Sabah state election in September: Pandemic fatigue, mass gatherings worsened by SOP non-compliance, illegal entry of immigrants coupled with crowded prisons and detention centres, and the increase in cases detected due to mass screening in targeted enhanced movement control order (Temco) areas. The government has since then continued efforts to detect more Covid-19 cases.

Malaysia ended 2020 with its highest-ever daily number of cases at 2,525 on December 31, but with 78.7 per cent of the 113,010 cases recorded throughout the year having recovered and with a death toll of 471 cases (0.42 per cent of all cases) and 20.88 per cent still under treatment.

Who can forget the acronyms MCO, CMCO, RMCO? First it was the ultra-strict movement control order (MCO) with lockdown-like measures to slow the spread of Covid-19 cases, which later evolved to more relaxed restrictions in the government’s bid to balance the need to protect lives and the economy.

Who can forget the acronyms MCO, CMCO, RMCO? First it was the ultra-strict movement control order (MCO) with lockdown-like measures to slow the spread of Covid-19 cases, which later evolved to more relaxed restrictions in the government’s bid to balance the need to protect lives and the economy.

The year 2020 has ended, but CMCO continues in certain places — almost the whole Selangor, Kuala Lumpur and Sabah — until January 14, and the most-relaxed version RMCO for the rest of Malaysia until March 31. Here’s your SOP-filled life in 2020 in a nutshell:

Can you recite the “new normal” practices that Malaysians had to get used to in 2020? Working and studying from home, physical distancing, crowd limits, temperature readings, using the MySejahtera app and of course — wearing face masks.

Can you recite the “new normal” practices that Malaysians had to get used to in 2020? Working and studying from home, physical distancing, crowd limits, temperature readings, using the MySejahtera app and of course — wearing face masks.

Just like in 2009 when the Malaysian government had to impose a maximum retail price of RM0.80 per piece on three-ply face masks due to the demand amid the H1N1 pandemic, Putrajaya in 2020 again had to control the maximum selling prices by initially increasing it to increase supply by encouraging production and imports, before bringing it back down to make it affordable for the public to buy as wearing one became mandatory and as supply conditions improved.

;

There was some cheer as the year ended, when the government confirmed that it had procured Covid-19 vaccines developed by US-German firms and a UK firm with the University of Oxford with sufficient dosages for 12.8 million persons or 40 per cent of Malaysia’s estimated 32 million population. These vaccines are due to arrive within the first six months of 2021.

The government’s initial target was to get enough Covid-19 vaccines for 70 per cent of the population to achieve herd immunity.

As of December 22, the government estimated that it will be spending RM2.05 billion out of a RM3 billion allocation to provide free Covid-19 vaccines to 82.8 per cent or 26.5 million of the Malaysian population, subject to ongoing negotiations with two suppliers from China and a Russia supplier to cover the remaining 42.8 per cent of the 82.8 per cent estimate.

2. Musical chairs in game of numbers for political loyalty

In just one action-packed week in late February, a string of events -— including the now infamous “Sheraton Move” and the Pakatan Harapan (PH) federal government’s collapse amid realignment of political loyalties and defections — changed Malaysia’s political landscape, leading to the new Perikatan Nasional (PN) federal government under Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin’s leadership.

Read here for a full recap of how Pakatan Harapan lost three state governments (Johor, Melaka, Perak) within two weeks from late February to early March with the turn of political tide, before going on to lose Kedah about two months later. Following much drama in Sabah politics and an early state election in September, the state too fell to PN and its allies.

Amid persistent challenges to the PN federal government’s legitimacy and its actual strength in numbers as well as unsuccessful bids to have voting in Parliament for no confidence motions, the federal Opposition saw the Budget 2021 vote as a chance to determine if there has been a loss of confidence in Muhyiddin’s leadership and to make way for a new government.

Amid persistent challenges to the PN federal government’s legitimacy and its actual strength in numbers as well as unsuccessful bids to have voting in Parliament for no confidence motions, the federal Opposition saw the Budget 2021 vote as a chance to determine if there has been a loss of confidence in Muhyiddin’s leadership and to make way for a new government.

On December 15, the PN administration was able to indirectly prove its support levels, by winning a wafer-thin margin of just three votes in the final vote on the Budget 2021’s third reading. The only MP absent during the vote was understood to be ruling party Umno’s MP Tan Sri Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah, who had the day before said he would abstain even as he urged others to vote with their conscience.

3. Unemployment at all-time high in years

Amid all the political upheavals and reshuffling of political positions, a growing number of Malaysians had to contend with losing their jobs as the economy took a hit due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Based on the latest official statistics up to October 2020, Malaysia’s unemployment rate peaked in May 2020 at 5.3 per cent, the highest since the 5.7 per cent rate recorded over 30 years ago for the entire year of 1989.

The same pattern can be seen even if unemployment rates in 2020 were compared by month or quarterly against other years, with the unemployment figures this year significantly higher.

The number of unemployed persons in Malaysia in 2020 went past 600,000 in March and has so far peaked at 826,100 persons in May, and has stayed at more than 700,000 cases for the months since then up until October.

These figures are all higher than the annual figures in the past 38 years, with the last highest figure in 2019 at over 508,000 unemployed persons for that year.

The number of unemployed persons in 2020 also stands out as being significantly higher compared to recent times, when examined either quarterly or monthly.

4. Malaysia recognises more Malaysians as poor after Poverty Line Income (PLI) revised

Under the 2005 method to measure poverty, Malaysia used RM980 as the national poverty line income, which meant that only households earning less than RM980 each month were officially recognised to be absolute poor, and with just about 24,700 households falling under this category.

But calls had been made since 2019 for Malaysia to update its outdated and unrealistic 2005 methodology of measuring poverty levels in the country, with a new method finally unveiled on July 10 as the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) released the latest official statistics on Malaysia’s poverty rates.

The new 2019 methodology is based on the minimum of household income required for healthy eating and quality non-food items, instead of just the minimum calorie levels required or minimum quantity of non-food items under the old 2005 methodology.

With the new PLI in 2019 now at RM2,208, more households in Malaysia find themselves falling below this monthly income level, with the number of poor households increasing from just around 24,700 in 2016 to 405,441 in 2019.

What this means is that Malaysia’s absolute poverty rate is officially higher than previously thought, at 7.61 per cent in 2016 and 5.6 per cent in 2019 under the new methodology, instead of less than 1 per cent of households being absolute poor under the old methodology.

4. Klang Valley water cuts

People in Klang Valley were seemingly dealt an extra bad hand this year, with a slew of unscheduled water disruptions that was not due to scheduled works such as repairs and upgrading.

The longest of the water supply cuts started on September 3 and lasted for six days in most affected areas. In total, the cut involved 1.2 million water accounts in 1,292 areas, encompassing the districts of Kuala Lumpur, Petaling, Klang, Shah Alam, Kuala Selangor, Hulu Selangor, Gombak and Kuala Langat.

Pollution of rivers caused the majority of the water cuts, which raised public anger with experts questioning the efficiency of water management agencies.

In response to the problem, the Selangor government in October stated it would invest RM200 million investment in initiatives that would supposedly reduce pollution incidents by 90 per cent.

Throughout the year, authorities have also made a number of arrests on those — typically factories or plant owners — who were found to have caused the pollution incidents, with the latest arrests happening in early December.