KUALA LUMPUR, Dec 5 — Lo was diagnosed almost 10 years ago with Stage Four kidney cancer, but the 57-year-old is still alive today and says he can live a normal life as he is on sunitinib, a targeted therapy drug that’s not available in public hospitals in Malaysia.

Even though targeted therapies — which block the spread of cancer by acting on specific molecules associated with cancer growth, unlike standard chemotherapies that kill both rapidly multiplying healthy and cancerous cells — have been on the market since the early 2000s, many of them (like sunitinib which is 10 years old) are not listed on the Ministry of Health (MOH) Medicines Formulary (FUKKM), also known as the Blue Book, that lists the medicines provided in MOH hospitals here.

“If you have the right medication, it’s okay. Cancer can be controlled,” Lo, who declined to provide his full name, told Malay Mail Online. “You don’t think you have cancer. Just go out every day, live as normal as possible”.

(Oncologists stress that treatment results for any drug depend on the individual. The website for sunitinib (brand name Sutent) says the drug is not a cure and does not produce the same results for everyone.)

Sunitinib — which Lo used to buy a few cycles of on his medical insurance as it costs RM15,000 to RM20,000 per 28 days — is provided free for the Sibu man as he has been on Pfizer’s patient assistance programme since 2009 when the drug was just registered in Malaysia.

Cancer is one of the areas that has been hit hard as government hospitals try to stay afloat amid budget cuts that have purportedly prevented some from even conducting pathology tests.

Clinicians say there is a lack of new cancer treatments in public hospitals in Malaysia because of this. Most of the oncology drugs listed on the Blue Book are between 10 and more than 20 years old.

They say drugs are considered old when their patent expires, which can range from five to 20 years. Dr Ho Gwo Fuang, oncologist from University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), said drugs below 20 years are mid-term as patents tend to expire within two decades, but there is no hard and fast rule.

The relatively new targeted therapies are expensive, according to oncologists, citing prices like RM6,000 or RM10,000 monthly for lung cancer treatment, RM8,000 per dose (two doses a month) for a colon cancer drug, and RM8,000 to RM15,000 per dose every three weeks for a breast cancer drug.

Datuk Dr Mohamed Ibrahim Abdul Wahid, medical director and consultant clinical oncologist from Beacon International Specialist Centre in Petaling Jaya, said lung cancer patients in Malaysia used to be told back in 1993 that they only had three months to live. But now, he said he has patients who survive up to eight years.

“Some are on the newer targeted therapies. If it’s not available, patients may die prematurely,” Dr Ibrahim told Malay Mail Online in a recent interview.

He said many tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which are a type of targeted therapy, for lung cancer are not available in the Blue Book. Neither is immunotherapy — a new treatment that harnesses the immune system to attack cancer — even though Malaysia approved an immunotherapy drug, pembrolizumab, for lung cancer and melanoma (deadliest form of skin cancer) earlier this year.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has named immunotherapy, which appeared on the market just a few years ago, the 2016 Advance of the Year, describing it as a “promising new strategy to treat cancer” as it may be able to control tumour growth and produce fewer side effects than chemotherapy.

According to Dr Ibrahim, most of the cancer drugs in the Blue Book are standard chemotherapies, while the few available targeted therapies like imatinib for leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumour, and trastuzumab for early stage breast cancer, have been on the market for more than 10 years.

The former Malaysian Oncological Society president said the government should negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for lower prices, instead of merely looking at affordability.

“Some of our neighbouring countries have got quite good access to some of these drugs,” said Dr Ibrahim, citing Thailand as being “far more advanced” in terms of government reimbursement of medicines.

“We can cure cancers. If you look at the incidence of breast cancer death in Western countries like the US, they’re dropping. Why? Because there’s better access in terms of screening, better access in terms of treatment.

“Mortality from cancer in Malaysia is, I’m ashamed to say, one of the worst in the region, even compared to South-east Asian countries,” he added.

According to a Pfizer fact file on the cancer burden in Asia, the survival rates for cancer among women in Malaysia is somewhere in the middle among regional rankings: worse than Singapore, Indonesia, and Cambodia, but better than Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Current Malaysian Oncological Society president Dr Matin Mellor told Malay Mail Online that new cancer treatment can prolong life and the disease can be cured if it’s detected at an early stage with available treatment.

“Generally, if disease has spread or is Stage Four, cure is not the goal of treatment,” he added.

‘Blue Book is a charade’

Dr Lim Teck Onn, vice chairman of cancer health advocacy group Together Against Cancer, said even if drugs are listed on the national formulary, they may not necessarily be funded by the government as it depends on the budget.

“This has happened especially for oncology drugs,” Dr Lim, who is a health researcher, told Malay Mail Online in a recent interview. “The Blue Book becomes a mechanism for the government to control the budget. If they can’t fund, that’s it”.

He pointed out that in other countries like Australia, the UK and Taiwan, however, all of their citizens get treated with the drugs listed in the national formularies and those governments use the Blue Book to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for lower prices.

“Your Blue Book is a charade,” Dr Lim told Putrajaya. “You’re not treating people”.

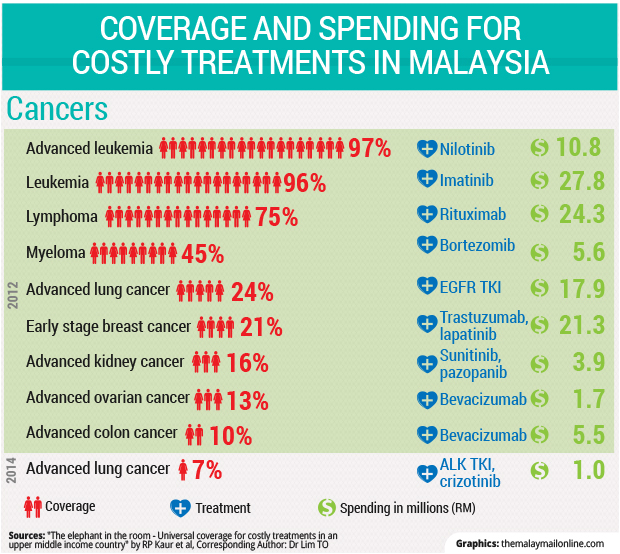

According to a paper where Dr Lim is a corresponding author titled “The elephant in the room — Universal coverage for costly treatments in an upper middle income country” that looked at the coverage of expensive cancer and non-cancer treatments in Malaysia from 2012 to 2015, coverage varied from universal for treatments like organ transplant, dialysis and nilotinib for leukemia, to practically none for certain treatments for hepatitis C, stroke and psoriasis (a skin condition).

In terms of cancer, the coverage of treatments for blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma was high at 96 per cent and 75 per cent respectively. But coverage of other targeted therapies for solid cancers was low, ranging from 7 to 24 per cent for advanced lung, colon, ovarian, kidney and breast cancers.

One interesting finding of the paper, which is under review for publication in the international Health Policy journal, showed that only 21 per cent of 1,508 people who needed the combined treatment of trastuzumab and lapatinib for early stage breast cancer in 2012 were treated, even though trastuzumab is in the Blue Book.

Dr Lim said high prices for drugs — such as the much talked about RM150,000 for sofosbuvir — were “nonsense” and that it was “all about volume.”

“If you say ‘I’ve got 5,000 people who need treatment’, the price will drop,” he said.

He also called for a change of Malaysia’s healthcare policies so that public hospitals will be reserved only for the poor, while the Public Service Department should negotiate with private hospitals and fund treatments for civil servants.

“Why can’t Socso pay for cancer care?” Dr Lim added. “The way we designed our health policies is not smart”.

MOH DG: New drugs have ‘marginal benefits’

MOH director-general Datuk Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah said the National Chemotherapy Protocol is revised from time to time and the latest revision is due for publication this year; he described it as a consensus guideline among oncologists and other specialists involved in cancer care.

“Some of the drugs or indications listed in this protocol is yet to be listed in FUKKM,” Dr Noor Hisham told Malay Mail Online, referring to the national formulary.

“Many of the new drugs have marginal benefits, with high cost, thus making them less cost effective, and thus they were not included in the latest revision,” he added.

The DG also said new drugs would be considered for the formulary if negotiations can bring prices down to those recommended by the ministry’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA).

“The JKKK Ubatan Onkologi has proposed the introduction of Value Based Medicine, which will enable a transparent and reproducible methodology for Health Technology Assessment to calculate and recommend a price that would bring the drug into the cost effective range, thus making it affordable to be reimbursed by a system that is funded by taxation,” he said.

Dr Noor Hisham also said some targeted therapies showed promising progression-free survival, but later analyses indicated that overall survival was similar to that of standard of care.

“Therefore, we cannot rush to list drugs too soon in the formulary. Adequate time must be given to allow the data and experience to mature, and sometimes this can take up to five years,” he said.

Cancer to be No. 1 killer

According to Dr Noor Hisham, cancer has risen from being the fourth cause of death in MOH hospitals in 2012 to third last year at 13.56 per cent. The disease was ranked as the second cause of death through 2013 to 2015 at private hospitals, comprising 25.58 per cent last year.

“Due to an increasingly larger proportion of the older population (or ageing population) as well as increase in population in country, it is expected that cancer will become the No. 1 killer,” he said.

The DG cited the First Five Year Report 2007-2011 that said 103,507 new cancer cases were diagnosed in Malaysia from 2007 to 2011. More women than men comprised these cases at 54.8 per cent compared to 45.2 per cent.

“The five most common cancers among males were cancers of the colorectum, lung, nasopharynx, lymphoma and prostate. Among females, the five most common were cancers of the breast, colorectum, cervix uteri, ovary and lung,” he said.

Dr Noor Hisham said the government spent RM240 million on cancer drugs last year out of RM2.3 billion on all medicines. A total of RM960 million was spent on treatments for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which are chronic diseases that are not passed from one to another, such as heart attacks, cancers, asthma and diabetes.

“There has been an increase in the budget for oncology drugs. Although we would like to see a faster increase, it is acknowledged that the same budget has to be shared with many disciplines and needs. One reason for the larger amount spent on non-cancer NCDs is the larger numbers of non-cancer NCD patients,” he said.

Not everyone can get treatment even if available

Dr Ho, oncologist from UMMC, said many of the new cancer drugs are not provided by public hospitals in Malaysia due to concerns on “cost effectiveness.”

The ones available include trastuzumab for early stage breast cancer, gefitinib and erlotinib for advanced lung cancer, pazopanib for advanced kidney cancer and imatinib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours. There are only four or five new drugs less than a decade old for solid tumours, he said. Solid tumours include breast, prostate, lung, and liver cancer.

“And when a drug is supposed to be available in the public hospitals, it does not mean that patients can automatically expect to be provided the drug. This is because budget is limited, and all patients share the same budget pool, so if the budget is used up early on, the rest of patients (who are supposed to be provided the drug) do not get their ‘supposedly entitled’ drug treatment. This situation may become more acute this year and the next few years due to the budget cut to health services,” Dr Ho told Malay Mail Online.

The Health Ministry’s budget was cut by RM280 million in Budget 2016 compared to the previous year. Deputy Health Minister Datuk Seri Dr Hilmi Yahaya reportedly told Parliament that the government had slashed the ministry’s funds by up to RM380 million for this year, but the money for medical supply was returned in stages.

The allocation for the health sector under Budget 2017 was increased by about RM2 billion from RM23.03 billion to RM24.8 billion.

Kampar MP Dr Ko Chung Sen from the DAP, however, said last October that despite the increase to the Health Ministry’s overall 2017 budget, the allocation for services and supplies under pharmaceuticals and supplies dropped by almost 19 per cent from RM1.6 billion to RM1.3 billion.

Healthcare media company MIMS reported that there is a RM600 million cut in the 2017 budget for the supply of medicines, consumables, vaccines and reagents.

“University hospital charges have slowly (or rather, quickly) but surely been going up for the past few years, with many patients already priced out of these hospitals and we have to divert patients away to the National Cancer Institute (IKN) or Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) now,” said Dr Ho.

He added that there was also a lack of cancer services in east Malaysia and in the east coast of the peninsula.

“Patients have to travel miles from Kuantan or from Kuala Terengganu to KL or Kota Baru to seek oncological treatment,” he said.

The oncologist urged the government to implement the National Strategic Action Plan for Cancer Control Programmes (NSPCCP) 2016-2020 that reportedly covers all aspects of cancer control like early detection, treatment and prevention.

“I feel the government should honour the expertise and effort put into the new National Cancer Control Plan, and support its recommendation and cost for implementation with the fund/ budget required, not ask us to design a plan on a shoe-string, or basically overrule the plan saying there is no budget, get the budget from your own MOH budget. How can that be successful? The MOH budget is already stretched with the current service, how to grow the service with the new plan?” Dr Ho questioned.

He also said it was unlikely that immunotherapy, touted as the biggest breakthrough in oncology since targeted therapy, would ever be available in Malaysian public hospitals, given the price tag of RM20,000 per shot for pembrolizumab for melanoma and advanced lung cancer (35 shots for two years).

“The most successful type to date is the so-called ‘checkpoint inhibitor’: pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab, which has produced some sustained long term survival for previously fatal cancers like malignant melanoma, lung cancers, bladder cancers, kidney cancers etc,” said Dr Ho.

“Many more indications are being experimented upon now: head and neck cancer, gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, triple negative breast cancer, lymphoma, to name but a few. This treatment will continue to mature and truly ‘cure’ many cancer patients in the next decade or two… watch this space,” he added.

UK daily The Guardian reported in June last year that immunotherapy is a “whole new way” of tackling cancer.

Cancer Research UK reportedly said cancer cells have developed a kind of “secret handshake” that persuades the body’s immune system not to attack them. Immunotherapy drugs are the long-term result of scientists’ efforts to disrupt a molecule on immune cells that is part of the “secret handshake.”

Oncology budget not enough

Pharmaceutical company Sanofi said “very few” targeted therapies are listed in the Blue Book even though they have been available on the market for several years, pointing out that its chemotherapy drug, cabazitaxel, for prostate cancer has yet to be listed even though it’s been on the market for several years.

“Budget for oncology currently is definitely not enough to support the new drugs that are being introduced in the market. Thus, it is advisable for the ministry to review the demand in market that requires government support, in order to provide a fair access to medicine in cancer therapies,” Kelvin Lam, general manager for Sanofi Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, told Malay Mail Online.

Roche Malaysia said since 2007, it has helped more than 4,000 cancer patients get access to medicines through its patient assistance programme that provides drugs for free.

“Most of Roche’s life-extending medications are provided through this programme. Many of these life-extending medications are not available on the Ministry of Health National Formulary,” the pharmaceutical company told Malay Mail Online.

“We believe that finding equitable and sustainable solutions to the national barriers to healthcare can only be achieved through persistent commitment and action by multiple stakeholders. This requires all players — public authorities, non-governmental stakeholders, local communities and the healthcare industry — to work closely together,” it added.

Pfizer Malaysia said its patient assistance programme for kidney cancer stopped in 2012 as it was a pilot, but patients like Lo continue to receive the drug for free until they no longer respond positively to medication. They also have partial assistance programmes for trizotinib, a targeted therapy, for lung cancer and non-oncology products.

“It’s our way of addressing the void in treatment in certain hospitals, or in certain settings, to help the patients,” Azwar Kamarudin, corporate affairs, health and value director of Pfizer Malaysia, told Malay Mail Online.

Pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Roche offer patient assistance programmes as part of their corporate responsibility to improve access to medicines.

Almost half of cancer patients encounter financial catastrophe

The 2015 ASEAN Costs in Oncology (ACTION) study by the George Institute for Global Health in Australia, which examined the social and economic impact of cancer in Malaysia and in seven other countries in South-east Asia, found that 45 per cent of cancer patients here encountered “financial catastrophe” a year after diagnosis. Financial catastrophe was defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 30 per cent of annual household income.

The 2015 ASEAN Costs in Oncology (ACTION) study by the George Institute for Global Health in Australia, which examined the social and economic impact of cancer in Malaysia and in seven other countries in South-east Asia, found that 45 per cent of cancer patients here encountered “financial catastrophe” a year after diagnosis. Financial catastrophe was defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 30 per cent of annual household income.

According to the longitudinal study that tracked 1,662 cancer patients in Malaysia through their first year after diagnosis, involving both MOH and university hospitals as well as private institutions, 11 per cent died a year after being diagnosed with cancer.

“In Malaysia, the most vulnerable segments of society are at greater risk (66 per cent financial catastrophe in low-income households),” said the study.

“Even patients in public hospitals face high out-of-pocket spending for many health services such as chemotherapy, biopsy, biomarker testing, innovative cancer treatments, and palliative care. University hospitals require more funds from Ministry of Education (MOE) to provide optimal support for cancer patients,” it added.

NCSM: Most cancers don’t need new drugs

National Cancer Society of Malaysia (NCSM) president Dr Saunthari Somasundaram said the majority of cancers do not require new, more expensive therapies.

“Over 80 per cent of cancers can be treated successfully by ‘older’ drugs, especially if the cancer is found in early stages. There are many cancers, if found in early stages, that do not require ‘drug’ therapy. Surgery and radiotherapy suffice,” she told Malay Mail Online.

She also stressed the importance of prevention and earlier diagnosis of cancer, saying that there are success rates of more than 80 per cent in some cancers with earlier diagnosis.

“To successfully manage cancer, we can’t focus on therapy only. When a patient is suspected to have cancer, how quickly that patient gets into the ‘system’ for investigations and diagnosis, the referral for treatment and compliance to that treatment is equally as important. The timeliness and compliance of treatment is equally essential to the type of treatment,” said the head of the NGO that provides cancer education, screenings and support.

A spokesman from non-profit MAKNA told Malay Mail Online: “The important thing is, as MAKNA has always maintained, to take better ownership of one’s health — go for check-ups and be health aware, because early detection can save lives.”

Hospis Malaysia, a charity that provides palliative care, said many cancer patients do not have access to even basic treatment because they don’t have faith in it or they prefer alternative treatments.

“Some patients come to hospital, get diagnosed and then seek alternative treatments,” Hospis Malaysia CEO Dr Ednin Hamzah told Malay Mail Online.

“As medicine becomes more of a business rather than a social care, are our doctors and hospitals really providing the best care or rather, trying to make as much money from patients? Similarly, that goes for pharmaceutical companies,” he added.