KUALA LUMPUR, July 16 ― There are two types of governments in the world: Those that build complex surveillance software to spy on their citizens, and those that buy them. Our government is more the buying type.

Few nation-states have the budgets to build out complex surveillance software, but many government are finding that ‘off-the-shelf’ software sold by dodgy companies are just as effective at a fraction of the price of developing that capability.

The problem with buying of course, is that sometimes those dodgy companies sell their wares to repressive regimes like Sudan, and being on the same customer list with Sudan doesn’t reflect well on you.

One such dodgy company is Gamma Corp, the organisation responsible for the FinSpy and FinFisher suite used by the Malaysian Government in the run-up to the 2013 general election.

Another is Hacking team, an Italian-based company that produces similar remote control software (RCS).

And in a bit of Internet karma, both these companies were hacked … possibly by the same person or group.

In August 2014, Gamma was hacked and had 40GB of data forcefully exfiltrated from its servers. My analysis of that leak revealed no information about Malaysian purchases of the FinSpy software, but that was a puny 40GB of data, or roughly three times more data than an iPhone can hold.

Recently however, Hacking Team had a much more severe attack, one that managed to extract 10 times more data, and here I found ample evidence of Malaysian government agencies procuring spyware ― presumably to be used against Malaysians.

The question of course is: Should you be worried? The answer is “Yes,” and not just for the obvious reasons.

After combing through a trove of documents, I found that three government agencies procured the ‘flagship’ RCS software from Hacking Team, and from my layman’s understanding of the law, none of them have the authority to actually use it.

Worst still, some e-mails point to incompetent IT skills as well as bad procurement practices that actually annoyed the supplier.

I will conclude this post with why this attack on Hacking Team has a positive outlook for regular Internet users, and why our government agencies procuring this stuff isn’t exactly ALL THAT BAD.

What did the Malaysian Govt buy?

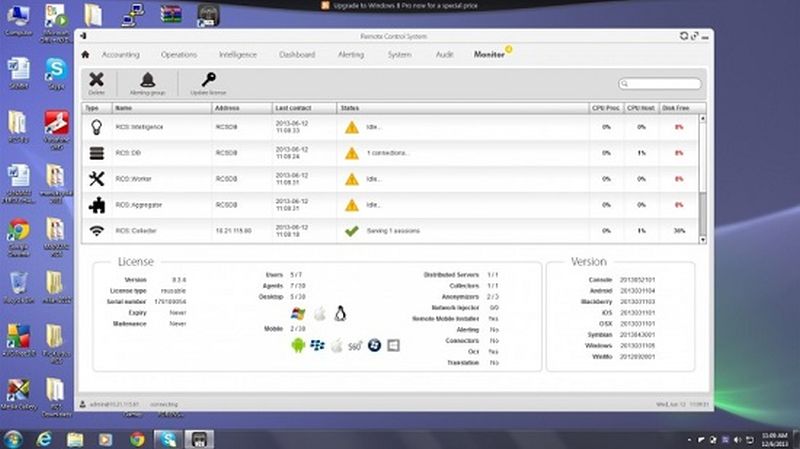

But let’s start with the RCS software itself. What exactly was being purchased?

Well, according to the Hacking Team brochure (you can download here):

Remote Control System (RCS) is a solution designed to evade encryption by means of an agent directly installed on the device to monitor. Evidence collection on monitored devices is stealth and transmission of collected data from the device to the RCS server is encrypted and untraceable.

RCS installations are deployed at the Customer’s premises, thus guaranteeing to the Customer total control on its operations and security.

In other words, RCS is a piece of spyware that, when installed on your computer or smartphone, begins monitoring you and your Internet usage, surreptitiously transmitting that information back the Command and Control (C+C) servers for further manual investigation.

This is quite a typical piece of surveillance software, no different from FinFisher and others we’ve seen before.

But make no mistake: This is spyware, meant to spy on people. And the last I checked, even government agencies need to go through proper procedures and have sufficient oversight.

RCS still requires to be implanted onto your system, and for this Hacking Team utilised vulnerabilities in software like Windows, Android and Flash that weren’t publicly known ― which means Hacking Team knew of weak spots in Flash that even the manufacturer wasn’t aware of, to bypass checks and protections so that its RCS agent could be implanted onto a victim’s machine.

These ‘zero-day exploits’ are rare to find. Researchers spend years looking for such things, and Hacking Team had quite a number of them.

Fortunately since this disclosure, those vulnerabilities are being or have been patched.

Which government departments?

Buying surveillance software in itself isn’t wrong. After all, the police are well within their authority to purchase such software as part of their investigative powers. It’s not just acceptable, it’s actually expected that the police would ramp up their surveillance capabilities ― phone taps and binoculars don’t get you enough information these days.

I don’t oppose specific surveillance, where the police in their authority and proper judicial oversight run a ‘stake-out’ on criminal suspects.

What I oppose is bulk surveillance, where the police without judicial oversight are given blank cheques to spy on whomever they choose. There’s a nuance that many don’t quite understand.

Of course, all of this violates the Computer Crimes Act, since the very act of using RCS is ‘hacking.’ Therefore, these government agencies, by just purchasing the software, have admitted to hacking citizens.

So which government departments purchased the software?

The ‘Government’ is a pretty abstract term that encompasses way too much. Let me be specific: There is evidence of three specific government departments buying products from Hacking Team.

These are the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, the Prime Minister’s Department (wrongly referred to in the e-mails as PMO or the Prime Minister’s Office, we believe), and a Malaysian intelligence body that goes by the name of MYMI.

Which begs the question: Does the MACC, PM’s Dept or MYMI have the authority to run surveillance programs?

From my reading of our laws like Pota (Prevention of Terrorism Bill) and Sosma or the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act, they only allow the police to spy on citizens, and only police officers above the rank of superintendent can intercept Internet communications without prior approval from the courts ― nowhere in any of those Acts does the law grant power to bodies like the MACC, and they certainly shouldn’t be granting power to the Prime Minister’s Department.

I could be wrong, but hopefully some lawyer reading this may correct my interpretation.

Of course, if MYMI was a police intelligence outfit, then obviously under the law it has the authority to operate such systems ― but again, does it have the right to hack a computer system? The Penal Code says it’s wrong to kill someone, but a police officer in a gunfight is allowed to. Are there such provisions in our legal framework to allow the police to hack into computer systems?

The question on my mind is, if the Prime Minister’s Department doesn’t have sufficient authority to run a surveillance programme, why is it buying surveillance software? Someone without a gun licence certainly shouldn’t be allowed to buy an M-16.

Although we probably shouldn’t worry, because a report from Hacking Team stated that “they (PMO) are not competent to use deploy RCS on their own.”

There is a Cyber and Space security division within the department, but we’re not talking security here – these are weapons. The difference between security and offensive software is that one secures servers, while the other is meant to break them.

Why would a ‘security’ division buy surveillance software? Don’t let the Government throw you off with words like cyber and security, this has nothing to do with either ― it’s purely an offensive application used to spy on people.

Income tax dept, IGP approval?

The invoicing data confirms these three government departments, while three others seemed to have been in the process of procuring Hacking Team software.

These include a “taxation agency” that had direct physical access to machines, the police’s Commercial Crimes Division and ‘PKSB,’ which was described as a very powerful outfit within PDRM (the Royal Malaysian Police), whose approval to procure Hacking Team software came from the IGP (the Inspector-General of Police) himself!

But once again, I have no issue with the police using this software, although the police should be aware that the names and passport numbers of five of their staff who took the training in Milan are up on the Internet. The names of the three staff from the Prime Minister’s Department are also online.

Also, why the hell is a tax agency buying spying software for? The answer lies in which tax agency gets 1.5 per cent of all taxes collected. I certainly hope the Computer Crimes Act doesn’t allow the LHDN (the Income Tax Department) to hack computers.

You also might notice industry regulator the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) on the list of ‘potential customers,’ but I didn’t find any e-mail in the stash to validate that.

Attribution

When we discover these RCS trojans in the wild, it’s usually very hard to attribute the attack to a specific actor. We’re left to make guesses based on the victim and the way the victim was hacked.

For example, in 2013, we saw a similar attack based on a file entitled “SENARAI CADANGAN CALON PRU KE-13 MENGIKUT NEGERI,” which led us to believe that not only were the targets Malaysian, but probably Malay-speaking Malaysians.

Here however, we see an interesting list of files used to create an attack.

Remember the ‘Bangladeshi voter’ incident in 2013 ― well, here we have evidence that the documents that went viral purportedly showing the Bangladeshis in our airports actually originated from the Government itself.

Let me repeat that: The Government itself was spreading rumours of Bangladeshi voters, not just the Opposition. Here is the WikiLeaks link in case you’re interested.

So while the Malaysian Government is complaining of social media being used to spread rumours, some government agencies themselves are responsible for some of the negative publicity ― presumably to get a gauge of which citizens are forwarding the ‘planted’ rumours.

There was a similar document about the indelible ink issue, and one rather formal looking document from the MCMC to Felda that was implanted with this spyware. The plot really does get juicy.

Juicy, juicy details

Let’s get into the meat of the subject: All three departments procured similar software, but all three had problems.

The MACC and Prime Minister’s Department procured theirs from a company called Miliserv Technologies that operates out of Kota Kemuning in Shah Alam.

This is not a small company. It was incorporated in 2005 with RM1 million in paid-up capital, and managed to secure more than RM8.4 million in contracts from Kementerian Dalam Negeri (Ministry of Home Affairs) ― on top of its sales of RCS. [RM1 = US$0.26 at current rates]

Without going into details of the company, suffice to say it isn’t really up to spec in supporting software of this complexity.

Its support staff had issues even troubleshooting a NAT (network address translation) problem, and in some e-mails were asking rudimentary questions like “Can this VPS support the anonymizer?”

What really tickled me was the fact that this ‘secretive’ government surveillance programme operated under the Cyber Security Divison of the Prime Minister’s Department was running on a … UniFi connection!

This is the equivalent of driving a top-of-the line Lamborghini on a kampung (village) dirt road.

I saw e-mails within Hacking Team complaining of the dynamic IP (Internet Protocol) of UniFi, recommending Miliserv to switch to fixed-IP broadband instead.

Less funny was the fact that screenshots confirm that the machines used for this multimillion-dollar spying operation weren’t even running genuine versions of Windows. [Microsoft Corp, please take note].

The MACC servers were also the ones discovered by Canadian-based Citizen Lab in its report at the end of 2014, and these were promptly moved to different countries.

What that means is that the MACC ran investigations on Malaysians (presumably), but had the data of that surveillance routed outside of Malaysia to Fort Lauderdale in the United States, and the Ukraine.

That’s not quite acceptable. The data transmission from an RCS installation might be encrypted, but I doubt the storage of that data is.

The big letdown for me was that the MACC and PM’s Department had Miliserv run their spying operations and not the agencies themselves, and in one case the server was hosted on Miliserv’s premises.

This is the problem: While the law may allow specific government agencies to run surveillance, it certainly doesn’t allow a third-party contractor to do it ― and what we have here is Miliserv staff having access to private data on Malaysians.

MYMI, on the other hand, procured its RCS through a secretive ‘K.’ In some ways. it’s quite smart to use a secret handle, thereby reducing the exposure you suffer when the other end of the e-mail suffers a catastrophic hack like this.

In other ways, it’s not so smart to sell millions of ringgit worth of surveillance software to a government department and do so while operating an e-mail address that ends with @hotmail.com.

It’s even less smart to have missing dongles shipped to your home address ‘attentioned’ to your real name. I can’t link to that e-mail as it is personal information, but we know who you are, ‘K.’

Plus, it seems strange that Malaysian intelligence was procuring surveillance software from a Hong Kong-based company, when the same manufacturer of that software already has a local partner.

Hacking Team staff were joking among themselves that they should start charging for the replacement dongles.

Then we have information that backs up the typical perception Malaysians have of their government: A couple of guys over at CyberSecurity Malaysia thought the best way to forge a ‘strategic’ relationship with Hacking Team was to fly five members from Malaysia to Milan for a meeting.

Listen, if you’re customer, the supplier comes to your office ― not the other way around.

Also, the Malaysians, for some reason, weren’t happy with just going to the Hacking Team office in Singapore, choosing Milan instead ― this is software, you don’t need to see a factory, why do you need to go to Milan? Haih!

What I found annoying was that these guys were smart in encrypting the invoices, and sending the encryption keys via SMS. That’s something we all can learn from this: Whenever sending private information via e-mail, encrypt via WinZip and send the password via a separate channel. Or send a link, and then destroy that link once the data is received. That way, you limit your exposure in time.

I’ve saved the best for last though: Miliserv Technologies sent and e-mail to Hacking Team claiming to be representing the Prime Minister’s Office, inquiring about a “Network Injector Appliance (NIA) especially about how to deploy an agent at the ISP”.

What the hell is the PMO requesting for spyware to be deployed at a Malaysian ISP for? Why do they need that?

What does all this mean?

E-mail wasn’t the only thing leaked in this hack. Source code to the RCS software and how it actually exploited operating systems like Android and Windows were also made available to the public.

Because of that, software manufacturers like Adobe, Google and Microsoft rushed to publish patches that fixed the vulnerability.

What that means was that the exploits that Hacking Team relied on to install their backdoor RCS no longer exist, rendering their product obsolete and, in some cases, completely useless.

Some may argue this is bad, and surely it’s bad for Hacking Team, and probably bad for local law enforcement agencies that rely on these tools.

This is why regardless of whether MYMI was indeed the special branch or something else, the point is moot, because by the end of the month, this expensive software that our Government procured won’t be worth anything.

But here’s another take on it: We just patched a ton of exploits that we didn’t know about before, rendering applications like Flash, Android, Windows more secure than they were before the hack.

Because we have to make the assumption that if a company like Hacking Team found these exploits, other companies, and certainly other well-funded government agencies, probably knew about them as well, and we just closed yet another door for them to spy on the public.

Perhaps they have more doors, perhaps they have only one, but the fact is: We work on securing software, and this is a step in the right direction.

Who is Hacking Team to make those judgements anyway? Why should a corporation get to decide which governments get to use exploits and which don’t?

Conclusion

We’ve known all along that governments buy surveillance software, and sometimes bend the laws to use it. This is just another confirmation of what we already strongly believed.

Post-Script: Can we trust the data?

I’ve said it before, e-mails aren’t good evidence, as any digital data can easily be replicated and forged to absolute perfection.

But this isn’t just e-mail, this is more than one million e-mails and a couple hundred documents surrounding Malaysia, and collectively they make for a much stronger case.

For example, all the e-mails appear consistent, both chronologically and factually. The e-mails from Miliserv come from people whose names match what we see in the SSM (Companies Commission of Malaysia) data for the company, and the names also correlate to Malaysian IC numbers in the e-mail chains that match data on the SPR (Election Commission) website containing the voter checklist.

Some e-mails list staff of the various government departments going for training, and those names are actual employees of the agencies. Addresses given are actual Malaysian addresses and a lot of the context is set to something only Malaysians would know, like the name of the secretary of Cyber Defense in the PMO, or the fact that Malaysia has an IGP ― and terms like UniFi are thrown around.

I went in very deep in analysing Malaysian e-mails, and this data breach involved many, many countries, yet I couldn’t find a single piece of data that was inconsistent with the story.

Also, together with the e-mails were those prized zero-day exploits I mentioned. As more and more of those exploits are discovered, they’ll get patched, reducing the effectiveness of RCS.

But because those exploits were also released, we can be fairly confident this is the real thing. You can’t forge those unless you’re sufficiently well-funded, and we’re talking around US$50,000-100,000 per exploit.

So either this 400GB of data was forged through an intricate plan that involved probably thousands of people, or the data was hacked.

As more data becomes available, and as more of the pieces fit together, it becomes more reasonable to assume that data was hacked rather than forged. ― Digital News Asia

*This story was first published here.

**Keith Rozario blogs at keithRozario.com covering technology and security issues from a Malaysian perspective. He also tweets from @keithrozario. This article first appeared on his blog and is reprinted here with his kind permission.