AUGUST 26 — The East Asian Summit (EAS) that will convene in Kuala Lumpur this October is unlike any other regional gathering in recent memory.

While Asean has always prided itself on being the convener of great power dialogues, the sheer density of competing interests that will descend on Malaysia as the chair is unprecedented.

The complexities facing the group chair are enormous, for the EAS is not just another diplomatic forum but a stage where tariffs, territorial disputes, and competing civilizational visions converge.

The EAS brings together Asean’s ten members and its dialogue partners, including the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, India, Russia, Australia, and New Zealand.

But this year’s summit has the added dimension of all five BRICS leaders attending, creating a convergence of blocs that has rarely been tested in the same room.

Malaysia, as the chair, is expected to ensure that Asean centrality remains intact while the world’s largest powers attempt to bend the agenda to their own strategic purposes.

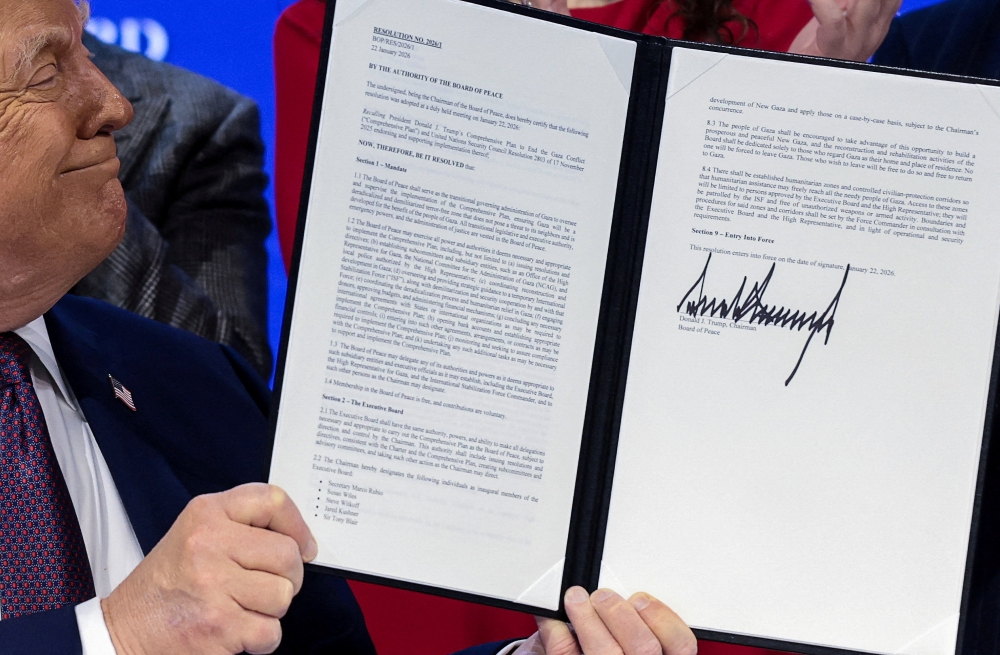

The timing is especially fraught with tensions as US President Donald Trump has returned tariffs to the center of Washington’s economic diplomacy.

China’s maritime presence in the East and South China Sea even as its economy slows make it no less daunting.

India finds itself squeezed by American tariff penalties for buying Russian oil, yet still seeks to present itself as a leader of the Global South.

Russia, freshly emboldened by its diplomatic maneuvering with the United States in Alaska, will want to frame the summit as an implicit recognition of its global standing.

Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea arrive carrying their own economic anxieties and security concerns, while the European Union watches nervously from the sidelines.

Asean’s structural dilemma

Asean is not designed to arbitrate such competing imperatives. Its strength lies in convening dialogue, not enforcing outcomes.

Yet the Kuala Lumpur chairmanship cannot afford to simply host the summit and hope for the best. Malaysia must carefully choreograph proceedings so that the EAS does not collapse into an unproductive standoff.

The dilemma is structural: Asean lacks hard power but carries the expectation of being the diplomatic “center of gravity.”

The challenge is therefore threefold: first, preventing the EAS from degenerating into a forum of rhetorical clashes; second, ensuring that concrete deliverables are announced, however modest, to justify Asean’s claim to centrality; and third, demonstrating that Asean is not just a bystander but an active manager of global tensions.

Malaysia’s role as chair is further complicated by the fragile state of Asean unity itself.

The recent border clashes between Thailand and Cambodia, and the cautious silence of member states on the worsening Gaza conflict, reveal an organization that is deeply divided on issues of war and peace.

To rally consensus among Asean members even before the EAS convenes is a difficult task, let alone balancing the competing strategies of Washington, Beijing, Moscow, New Delhi, and Brasília.

The Kuala Lumpur summit is far more than an Asean exercise in process.

It could determine whether regional institutions remain relevant in an era of great-power polarization.

With BRICS leaders present, the EAS risks becoming a parallel arena of contestation to the G20, with tariffs and technology restrictions as the language of confrontation.

If the United States continues to privilege punitive tariffs as its main instrument of leverage, and if China refuses to temper its maritime ambitions, Asean will face enormous pressure to prevent the summit from unraveling.

A minimalist approach may be the only viable option. This would involve securing agreement on a limited tariff framework, extracting a reaffirmation of the UN Charter’s principles under Chapter VIII, and pushing forward a modest Code of Conduct on the South China Sea—even if its binding nature remains disputed. These may sound incremental, but they would represent significant achievements in the current climate of hostility and distrust.

Navigating between hegemons

Malaysia, as host, has often excelled at the delicate art of balancing rivalries.

During the Cold War, it positioned itself as a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement while also being a founding member of Asean. Today, the stakes are even higher.

The ability to navigate between American preponderance, Chinese assertiveness, Russian opportunism, Indian non-alignment, and Brazilian demands for equity could define Malaysia’s diplomatic standing for years to come.

This balancing act will require more than the “Asean Way” of quiet consensus. It demands what can be called the “Asean Will”: the collective political determination to hold difficult conversations, confront disagreements openly, and hammer out compromises that prevent escalation.

Without such will, Asean risks being reduced to a ceremonial host while the real contest plays out above its head.

Conclusion: Enormous but not insurmountable

The complexities of the EAS in Kuala Lumpur are enormous because the chair must manage not only great-power disputes but also Asean’s own internal fragilities.

Yet the challenge is not insurmountable. If Malaysia can steer the EAS toward constructive outcomes—however modest—it will reaffirm that middle powers and regional organizations still have agency in shaping global order.

The world will be watching closely. Whether Asean emerges from the Kuala Lumpur summit as a credible convener or as a passive bystander will depend largely on the skill, patience, and resolve of the Malaysian chair. History will judge whether this was the moment Asean rose to the occasion—or the moment it allowed itself to be sidelined.

* Phar Kim Beng, PhD is the Professor of Asean Studies at International Islamic University of Malaysia and Director of Institute of Internationalisation and Asean Studies (IINTAS).

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.