NOVEMBER 16 ― The three main political coalitions have released their manifestos, with GE15 days away.

Manifestos may not be “holy books”, but they tell us something about what coalitions stand for (outwardly at least). And when the elections are over (assuming one coalition does win or is dominant), we can use the manifesto to hold the winning coalition to account.

“Women” feature prominently in each manifesto ― for perhaps obvious reasons.

Which manifesto has the best to offer for women?

While we can’t definitively answer this, I suggest a framework for analysis ― asking five questions of each manifesto. I also offer some thoughts on policy commitments I feel are particularly noteworthy.

1. ‘Bread and butter’ issues

First, we must ask if the manifesto is strong overall.

When you hear “women” and public policy, you may imagine specific programmes targeted at women. Those programmes are important, but are a small part of any policy agenda.

Instead, we must first think of “bread and butter” issues that any voter ― including women ― would care about.

It is beyond this article to cover all these issues, but it’s an important point to remember.

2. Gender mainstreaming

Second, we can ask whether the manifesto “mainstreams” gender.

It is not enough to identify “bread and butter” policy issues. We must also ensure that these policies ― and policies in general ― work for all regardless of gender.

Each manifesto seems to have one commitment on mainstreaming gender.

Harapan commits that “every Bill presented in Parliament will be guaranteed to possess gender inclusivity elements”. This would have significant impact.

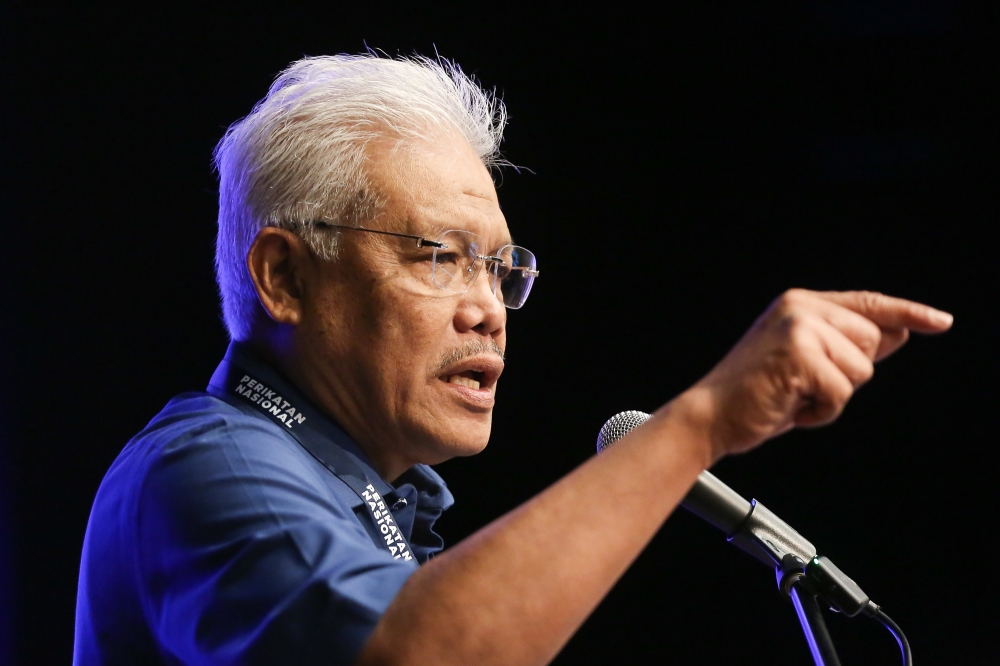

Meanwhile, BN commits to “conduct a needs assessment to establish a Gender Equality Tribunal”, and PN commits to “strengthen a strategic plan towards achieving gender equity (“kesaksamaan”) by 2030”.

BN’s and PN’s commitments could be impactful, but that depends on the outcome of the “needs assessment” and the content of the “strategic plan”.

3. Anti-discrimination and positive measures

Third, we can ask whether the manifesto addresses discrimination against women.

We are still not talking about “specific women's programmes”.

Instead we are now asking: how do we address discrimination, which stops women from enjoying equal rights and opportunities (at work, at home, in public, etc.) as men.

On discrimination in citizenship rights:

It's quite clear to me: Harapan’s commitments are stronger than BN, and BN’s stronger than PN.

Both BN and Harapan commit to amend the Federal Constitution so Malaysian women can automatically confer citizenship to children born abroad. Harapan has additional commitments on related citizenship issues.

Meanwhile, PN only commits to “finalising a study” on the relevant Constitutional amendments.

Next, on discrimination in employment:

Harapan commits to address “all forms of discriminatory barriers ... in the workplace” including the gender wage gap.

BN and PN do not mention employment discrimination, but commit to incentivise women’s work.

BN proposes tax incentives for companies that “uphold gender and ethnic diversity in management” and “introduce flexible working hours for working mothers”.

PN sets a gender target ― promising “aggressive interventions” to ensure women make up at least 30 per cent of “main positions in the public and private sectors” by 2025.

Additionally, BN and PN both propose supply-side incentives. BN commits to “full income tax exemptions for 5 years” for women returning to work; while PN commits to “increase the tax exemption rate by RM1,000 for all working women”.

While Harapan sets out broader goals on workplace discrimination, BN and PN describe specific and strong interventions.

In addition to employment, the manifestos make other promises on economic participation.

Harapan and PN both propose funding and training for women entrepreneurs.

Harapan proposes a “minimum quota of 40 per cent for women and the disabled” for these programmes, while PN proposes to increase interest free loans for women entrepreneurs (under DanaNita) to RM20,000 per person.

Meanwhile, BN proposes establishing new institutions: a “Women’s Economic Development Bank” and a “Women’s Economic Development Corporation”.

BN’s proposed new agencies could be more impactful than Harapan’s and PN’s proposed policies, but we’d need to know how the new agencies differ from existing agencies (which have gender specific programmes).

Lastly, closely related to economic participation, is higher education.

Harapan’s manifesto promises to address “all forms of discriminatory barriers especially in the education” (gender is not specified).

BN makes more ambitious commitments, promising “the first Women’s Public University” and a “Women’s Leadership Academy at a Public University”.

4. Child care (and other care work)

Our fourth question for the manifestos is on care work.

In addition to combatting discrimination, we must remove other barriers constraining women. Perhaps the biggest barrier of all is the unfair care burden.

Women disproportionately perform care work (for children, but also for other dependents), which makes it harder for women to work and pursue other interests.

Positively, care work features prominently in all three manifestos.

Each manifesto proposes to increase accessibility of early childhood care and education.

Harapan commits to providing child care subsidies for B40 and M40 women.

On the other hand, BN and PN commit to expanding publicly run child care.

BN promises “free national early childhood care and education for all children six years of age and under”, and PN promises “extending operating hours of Perpaduan and KEMAS nurseries until evening”. PN also proposes to introduce incentives for nurseries at work.

Beyond early childhood care, Harapan also commits to broader child care policies including making “One Stop Caregiving Facilities” in communities compulsory, and to working with NGOs to provide after-school spaces for children.

PN also commits to providing free child care centre services for the poor (the age group isn’t specified), and digitalising nurseries to enable monitoring of children.

Additionally, Harapan and PN also promise to professionalise the caregiving sector.

Notably, PN also proposes increasing paternity leave to 14 days (from seven days).

Care for elderly, persons with disabilities, and others are also highlighted in the manifestos.

For care work, all three manifestos offer fairly bold solutions.

Perhaps the most significant is BN’s commitment to free and universal early childhood care.

This has been done in other countries, and Malaysia already has a strong foundation (existing KEMAS centres and universal primary education) to build upon.

Studies suggest that publicly run child care may be preferable to demand-side policies (eg. subsidies for parents), and that universal access is preferable to targeted access (eg. only for the poor).

5. Women’s social welfare

Fifth, we ask how well women’s social welfare is addressed. This is towards ensuring all women can live with dignity.

In the manifestos, proposals on gender-based violence, women’s health, and financial assistance relate to social welfare.

On gender-based violence, BN and PN both commit to implementing the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act. The Act is already law, and so we expect any government to implement it.

PN commits to pass the Anti-Stalking law, which is important since the bill has yet to pass the Senate.

Most notable perhaps is Harapan’s commitment to resume implementation of the National Strategic Plan in Handling Causes of Child Marriage 2025. This plan was adopted by the Harapan government in 2020, but progress has stalled since the Sheraton Move.

Neither BN nor PN address child marriage in their manifestos.

On women’s health both Harapan and BN make noteworthy commitments.

Harapan commits to “free sanitary pads and tampons at all primary and secondary schools” and also for B40 women. This could solve period poverty.

BN commits to “establish the first Women’s Public Specialist Hospital”. A women’s hospital could address women’s specific health needs, as well as help ensure mainstream medical research and services cater to women appropriately.

BN also commits to “develop a national subsidy scheme for mammogram tests and cervical cancer screening programmes”.

On financial assistance, all three coalitions propose cash transfers for parents.

Harapan’s is the most generous, promising universal monthly cash assistance for children (up to 6 years old).

BN promises “one-off RM500 cash assistance to Bantuan Keluarga Malaysia recipient mothers who have given birth”.

PN promises “special care allowances for parents” (details are not specified).

Conclusion

I won’t provide a verdict on who’s manifesto is best for women ― partly because I’m a man, but also because I don’t think there is an objective “winner”. Much depends values and preferences.

However, I’ve suggested five questions which I hope will help you decide for yourself. I’ve also provided some insights into policy commitments I felt were particularly noteworthy.

Before I end, I’ll put forward one more consideration.

A manifesto's worth ultimately depends on the credibility of the party implementing it.

And so, a final question to ask: which coalition can we trust to do what they say?

* Ren-Chung has worked in gender equality and public policy in Malaysia for over a decade. He is currently pursuing an MSc in Public Policy Research at the Blavatnik School of Government, at the University of Oxford. Connect @renchung.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.