JANUARY 3 — Malaysia is a signatory to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). The UNCAC is an international instrument to address the scourge of corruption at the global level.

The adoption of the UNCAC in 2003 sent a clear message that the international community was, and continues to be, determined to prevent and control corruption. It should warn the corrupt that betrayal of the public trust will no longer be tolerated.

The UNCAC is the international community’s affirmation of the importance of core values such as honesty, respect for the rule of law, accountability and transparency in promoting development and making the world a better place for all.

A landmark instrument, the UNCAC introduces a comprehensive set of standards, measures and rules that all countries can apply in order to strengthen their legal and regulatory regimes to fight corruption. It calls for preventive measures and the criminalisation of the most prevalent forms of corruption in both public and private sectors.

It also requires member states to return assets obtained through corruption to the country from which they were stolen — a major international breakthrough as the UNCAC offers a framework for effective action and international cooperation.

In his Foreword to the UNCAC, then Secretary-General Kofi Annan wrote of the provisions therein contained:

“These provisions — the first of their kind — introduce a new fundamental principle, as well as a framework for stronger cooperation between States to prevent and detect corruption and to return the proceeds. Corrupt officials will in future find fewer ways to hide their illicit gains.

“This is a particularly important issue for many developing countries where corrupt high officials have plundered the national wealth and where new Governments badly need resources to reconstruct and rehabilitate their societies.”

On illicit gains in particular, Article 20 states as follow:

“Subject to its constitution and the fundamental principles of its legal system, each State Party shall consider adopting such legislative and other measures as may be necessary to establish as a criminal offence, when committed intentionally, illicit enrichment, that is, a significant increase in the assets of a public official that he or she cannot reasonably explain in relation to his or her lawful income.”

Even though Article 20 above recommends that member states should criminalise illicit enrichment, some — including Malaysia — have yet to specifically legislate on the matter. And there is “no unanimous applied definition of illicit enrichment”, despite the term is therein defined in Article 20 as a “significant increase in the assets of a public official that he or she cannot reasonably explain in relation to his or her lawful income.”

As such, based on his research on the laws around the world, Andrew Dornbierer offers the following definition:

“The act of illicit enrichment can be broadly defined as the enjoyment of an amount of wealth that is not justified through reference to lawful income”. (Dornbierer, A., 2021. Illicit Enrichment: A Guide to Laws Targeting Unexplained Wealth. Basel: Basel Institute on Governance.)

The phrase “not justified through reference to lawful income” refers to an absence of evidence that demonstrates the legitimate or non-criminal sources from which the enjoyed wealth was derived (such as salaries, profits from legitimate businesses, pension payments, inheritances, gifts or even loans from banks).

Dornbierer offers a simple example:

If an individual worked as a public tax assessor from 2010 to 2020 and earned a cumulative total salary of US$400,000 during this period, but instead was found to possess US$4,000,000 in his bank account at the end of this period, then if it is not possible for the individual to demonstrate that the additional US$3,600,000 was derived from other existing sources of legitimate income during this time (such as a loan from a bank, earnings from a side business, or the receipt of inheritance) then under an illicit enrichment law, the court may presume that this unjustifiable increase in wealth has not been derived from lawful sources and will impose a relevant sanction, even if no evidence of underlying or separate criminal activity is presented to the court.

In simple words, illicit enrichment is wealth that is not lawful income in the absence of evidence that shows otherwise.

In his book, Dornbierer annexes a compilation of illicit enrichment legislation and other relevant legislation which he categorises as either:

- Criminal Illicit Enrichment Laws

- Qualified Criminal Illicit Enrichment Laws

- Civil Illicit Enrichment Laws

- Qualified Civil Illicit Enrichment Laws

- Administrative Illicit Enrichment Laws; or

- Other Relevant Laws

As the above indicates, the book provides a comprehensive guide to illicit enrichment laws and their application to target unexplained wealth and recover proceeds of corruption and other crimes. The book covers both criminal and civil-based laws from around the world.

Malaysia’s only entry in the compilation of the laws falls under the second category above. It is qualified criminal illicit enrichment law because it requires the state to provide evidence to a court of a “reasonable suspicion” or a “reasonable belief” that some sort of underlying or separate criminality has taken place.

The law is in section 36 of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) Act 2009 which provides for the powers to obtain information, based on the investigation carried out by an officer of the Commission, that any property is held or acquired by any person as a result of or in connection with an offence under the Act.

In recent years, a concept has gained traction: unexplained wealth. It refers to valuable assets belonging to officials — or others in positions of power and influence — that are clearly incommensurate with their publicly-declared earnings or known business interests. (See Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), ”What is ‘unexplained wealth’?“)

At the heart of the concept is a very simple mathematical formula: Unexplained wealth = Total wealth less lawfully acquired wealth.

Thus, a person whose total wealth is RM5 million, and whose lawfully acquired wealth is RM2 million, can be said to have unexplained wealth of RM3 million.

The concept is now a key element in the United Kingdom’s Criminal Finances Act 2017 (CFA) — nicknamed “McMafia” laws after the BBC’s organised crime drama — which introduces new measures to help law enforcement act on corrupt assets.

One of the measures is what is called unexplained wealth orders (UWOs).

UWOs give enforcement authorities such as the National Crime Agency (NCA), Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) the ability to seize assets suspected of deriving from the proceeds of criminal activity.

A UWO places the burden on the individual, rather than the enforcement authority, to prove how he or she has accumulated his or her wealth. He or she is to produce evidence to verify the sources of the wealth, failing which the property may be recoverable by civil forfeiture.

Account or interim freezing orders (AFOs/IFOs) may also be made and penal sanctions imposed. UWOs thus provide an opportunity for enforcement authorities to confiscate assets without ever having to prove that the property was obtained from criminal activity.

According to Dornbierer, both terms — illicit enrichment and unexplained wealth — are currently being used interchangeably to refer to the exact same, or an incredibly similar, set of circumstances.

Both are controversial legal concepts. Some view them as critical tools in the combating of corruption and other crimes and the recovery of assets while others view them as a violation of common legal principles. But effective both have been in combating corruption and the recovery of proceeds of crime.

Dornbierer writes:

“[T]here is no doubt that [the] laws have remarkable potential in the field of asset recovery. Following the successful application of these types of laws in a number of jurisdictions, it is no surprise that an increasing number of countries are turning to these mechanisms to target corruption and criminality in general, and recover proceeds of crime.”

Malaysia may not count as one of those increasing number of countries. But the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government — to its credit — did consider introducing a legislation similar to the CFA with similar measures.

Then finance minister Lim Guan Eng said that measures like UWOs would enable the government to seize “extraordinary assets” owned by individuals, especially politicians.

“We want to get the government’s money back, this is why the attorney general is studying this provision introduced in the UK,” he said during a dialogue session on Budget 2019 at Equatorial Hotel.

Nonetheless, Malaysia should send a clear message that it is determined to require officials and individuals in positions of power and influence to “explain” assets belonging to them that are clearly incommensurate with their publicly-declared earnings or known business.

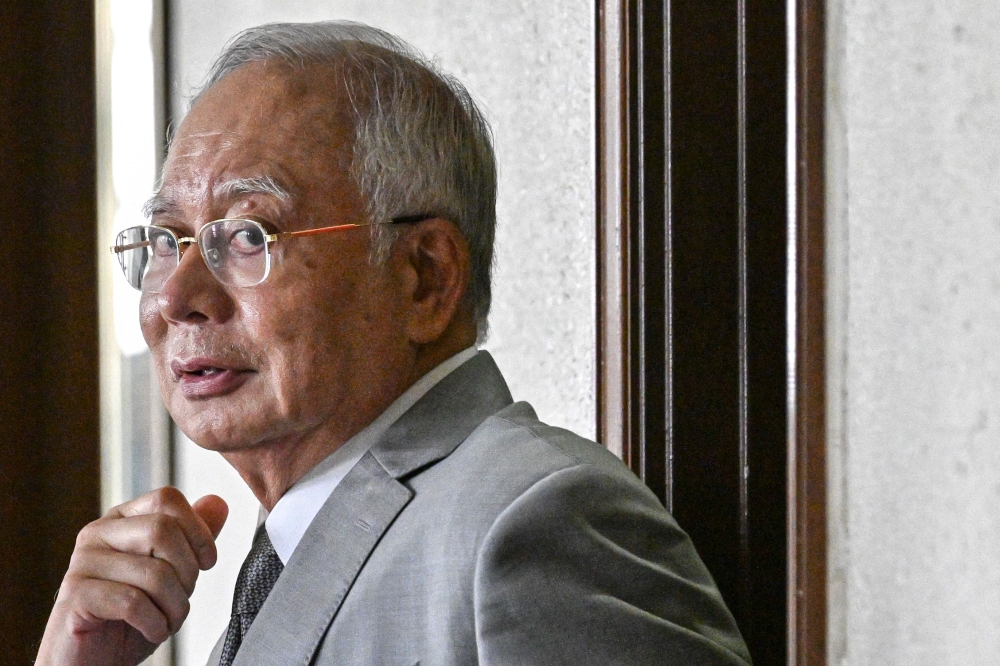

This by requiring the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) chief commissioner Tan Sri Azam Baki to break his deafening silence over his alleged ownership of millions in publicly traded stocks.

It is unexplained silence.

As Transparency International Malaysia (TI-M) president Muhammad Mohan said, it will affect the perceptions the rest of the world has on Malaysia and the MACC. These will, in turn, potentially bring down indices such as the Corruption Perceptions Index and Global Corruption Barometer.

* This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.