NOV 25 — Budget 2021 is rousing controversy for its disproportionate allocation of funds for Malaysia’s ethnic groups.

As widely reported, Bumiputera-targeted programmes stand to receive RM11.1 billion, dwarfing the RM530 million or so designated for non-Bumiputera causes. The Indian community, whose urban average household income is basically equal to that of urban Bumiputera households, receive a mere RM120 million.

Selayang MP William Leong has publicly denounced the Budget because it lacks inclusiveness and solidarity and propagates ethnicity-based policies. Penang-based NGOs have protested the meagre assistance for the Indian community. Voices have weighed in, some lambasting the government for failing to present a “Malaysian budget”.

These concerns, and the underlying anger and disappointment, are understandable. In the face of pandemic and recession, all Malaysians facing hardship should be assisted.

But sweeping objections do not get very far. We dearly need to look at the bigger picture of ethnicity-based allocations in recent Budgets, and the purposes and limits of economic relief and group empowerment policies, to be more precise in debating this Budget.

Three important issues need clarity.

First, the Bumiputera-non Bumiputera disproportionalities are exceedingly wide in Budget 2021, but actually not that much greater than the recent Budgets.

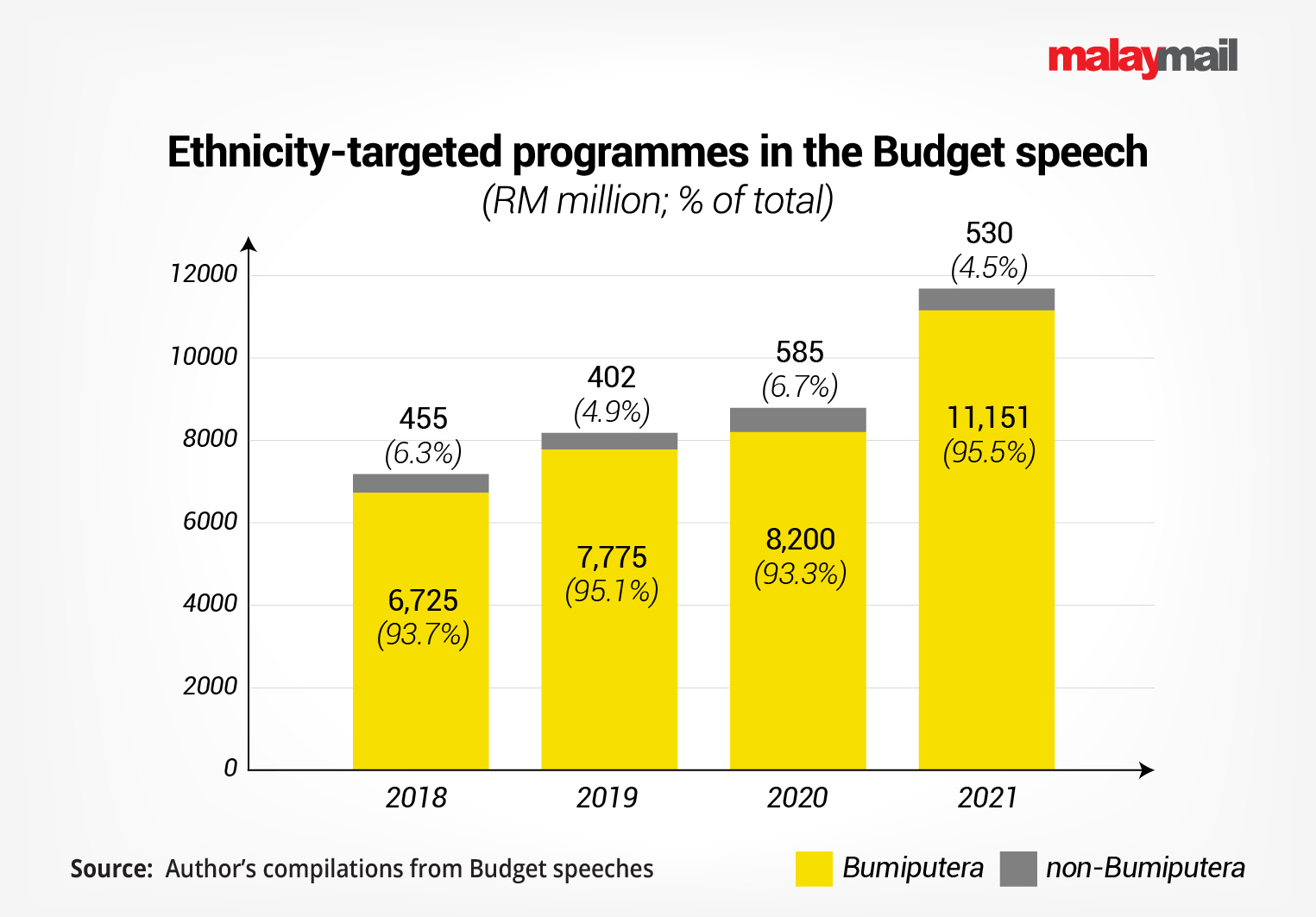

Based on the Budget speeches – which are not comprehensive but can be regarded as covering government’s top priorities for each group – proposed Bumiputera allocations for 2021 account for 95.5 per cent of all programmes targeted at ethnic groups.

For Pakatan Harapan’s Budgets of 2019 and 2020, the Bumiputera share was only slightly lower, at 95.1 per cent and 93.3 per cent, respectively.

This persisting state of affairs mirrors the political weight of the Bumiputera agenda; the phenomenon, and chorus of minority complaints, are not new. Pakatan went to great lengths to affirm and expand Bumiputera development.

This persisting state of affairs mirrors the political weight of the Bumiputera agenda; the phenomenon, and chorus of minority complaints, are not new. Pakatan went to great lengths to affirm and expand Bumiputera development.

Of course, the political difference is stark. While multi-ethnic Pakatan sought to boost its dismal Malay popularity, Malay-centric Perikatan Nasional panders to its base.

But regardless the government of the day, no one who wants to keep power will drastically disturb the system, which is deeply entrenched and broadly disburses benefits to millions of ordinary Bumiputera households.

This doesn’t mean that we cannot critique and change the system, but we must clearly articulate the grounds for doing so.

A second step in wading through this morass is to clarify the objectives and target groups of social policies, and the extent to which others may be excluded.

By and large, welfare assistance such as cash handouts, wage subsidy, loan moratorium, unemployment benefits, and others that are coming to the aid of struggling families, are available to all Malaysians.

If our concern is whether Malaysians of all ethnicities are receiving sufficient help, our primary focus should be on the adequacy of these measures and the funding. Bumiputera programmes operate in a separate sphere.

The principal purpose of Bumiputera programmes is to promote economic participation and upward mobility, by providing scholarships or special access to higher education, helping people start businesses through loans and other support, and facilitating micro, small and medium enterprise (MSME) growth.

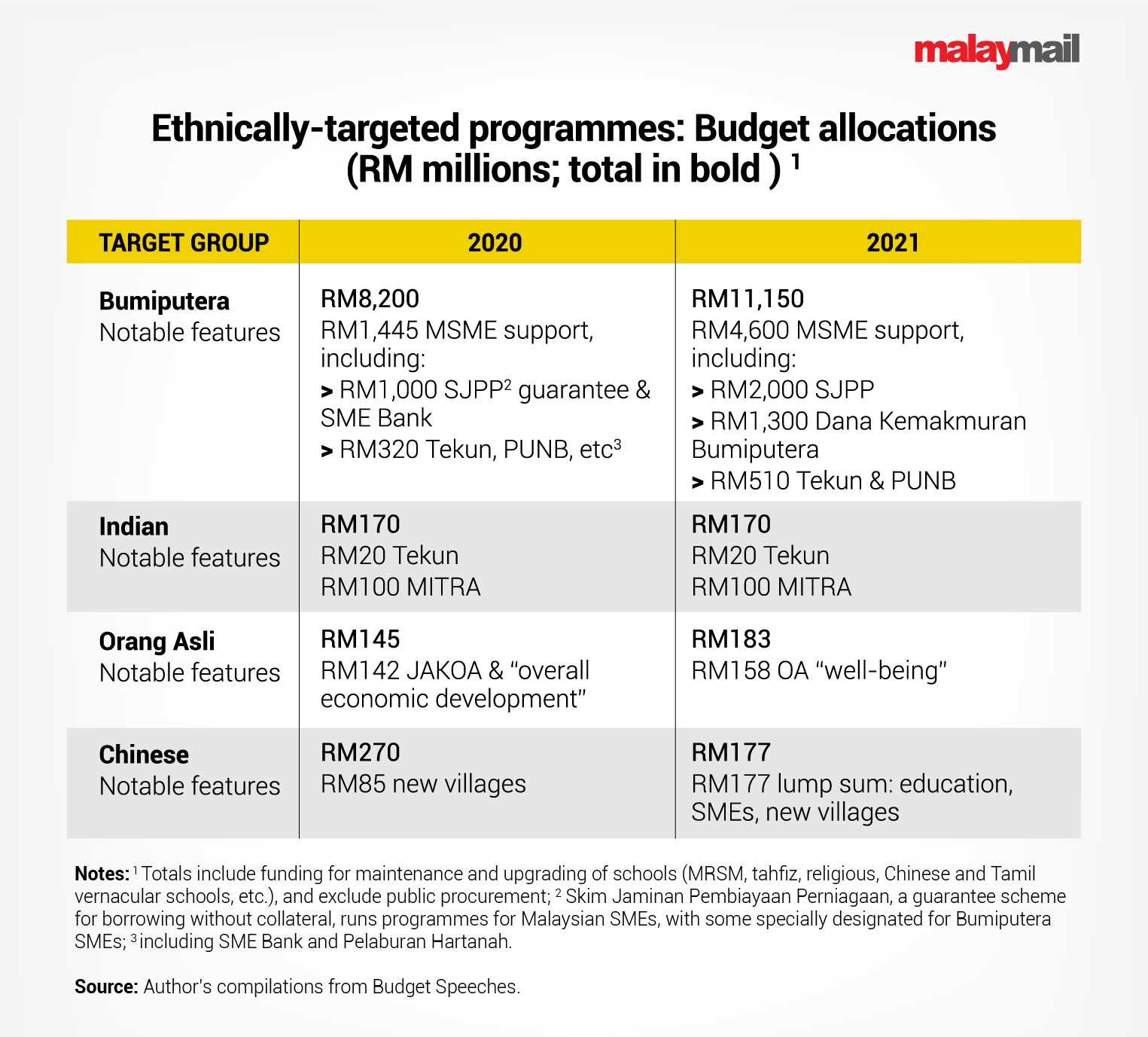

The table outlines ethnically-targeted programmes noted in current and preceding Budget speeches, and added a few informative notes. We can observe from these data that a large increase in funding for Bumiputera SMEs account for the bulk of the increase in the overall Bumiputera-targeted Budget – from RM8.2 billion in 2020 to RM11.1 billion in 2021.

Specifically, funding for the Dana Kemakmuran Bumiputera for SMEs and Skim Jaminan Pembiayaan Perniagaan (a guarantee scheme for non-collateralised loans) balloon by RM2.3 billion.

The government should be more precisely challenged to justify the timing and quantum of this massive expansion in funding for SMEs, at a time of heightened flux and uncertainty.

The government should be more precisely challenged to justify the timing and quantum of this massive expansion in funding for SMEs, at a time of heightened flux and uncertainty.

Of course, new ventures are necessary, even opportune; those who can innovate and invest in potential growth areas deserve support. But massively promoting these pursuits is also fraught with risk, raising questions on the prudence of this huge infusion of funds at this time.

Instead of being lavish, why not be more selective and restrained, moreover when the beneficiaries here are likely to be relatively economically secure?

A third issue we can think through more clearly revolves around programmes overseeing self-employment and micro-enterprise, and higher education.

One priority area for Budget 2021 is to provide support for the unemployed or low-income households, to start their own micro or small business. We see a substantial increase in allocations for Tekun and PUNB, two financial institutions serving this niche area for Bumiputeras.

While much of the criticism about the pittance designated for Indians has centred on the RM100 million for the Malaysian Indian Transformation Unit (MITRA), the RM20 million allocation for Tekun – which has operated one scheme specially for Indians – is more staggeringly paltry.

Tekun is not a panacea for the community’s myriad disadvantages, but disparity in allocations for Bumiputeras and Indians – under the same microfinance banner – demands answers.

Higher education prospects of many low-income and disadvantaged youths will be mightily hampered by current conditions. Yayasan Peneraju Pendidikan Bumiputera (YPPB), which expressly reaches out to B40 households struggling to attain technical and professional qualifications, will be filling an acute gap.

Among programmes that have started out as a Bumiputera preserve but subsequently opened to other communities, YPPB is arguably the most welcome and potentially impactful to follow suit.

Demands for more provisions for minority groups could zoom in on institutions like YPPB to be opened up to B40 non-Bumiputeras, as Tekun did.

Yes, Budget 2021’s disproportionalities in pro-Bumiputera versus other ethnically-targeted programmes are problematic. But debate that recycles sweeping and familiar complaints, and fails to present clearer and sharper criticisms, mainly generates heat with minimal light.

* Lee Hwok Aun is a Senior Fellow, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

** This is the personal opinion of the writer(s) or organisation(s) and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.