JUNE 15 — The Covid-19 pandemic has taken the world by storm. It has infected millions and caused thousands of deaths. As scientists and investigators continue to investigate the actual source of the virus, conspiracy theories of it being a bio-weapon has surfaced with China and the US accusing each other of having engineered the virus. Though these accusations remain unfounded, it does highlight the threat that bio-terrorism poses to the world.

A parallel can be drawn between the Covid-19 outbreak and a bio-terror attack. A successful bio-attack has the potential to have much worse consequences than the current Covid-19 outbreak. Bio-terror attacks have the capability to strike shock and terror in the society, disrupt a nation’s economy and cause mass casualty. The effects of some agents may have long term effects on survivors of attacks.

Biological weapons come under the category of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) which can be divided into chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) elements. A bio-weapon can be classified into bacterial agents such as anthrax; toxins such as botulinum and ricin; and viruses such as smallpox and haemorrhagic fever. Both state and non-state actors have actively produced and pursued the use of bio-weapons.

The Japanese terrorist-cult group Aum Shinrikyo who carried out the 1995 Tokyo Subway attacks using the nerve agent Sarin was one of the first groups to have successfully carried out a WMD attack. They had spent millions of dollars and had an army of scientists from top universities actively trying to weaponise other bio-agents such as anthrax and botulinum toxin.

Jihadist groups such as al-Qaeda have also actively pursued WMD. Al-Qaeda had chemical and biological weapons facilities in Darunta, Tarnak Farms (one of bin Laden’s former residences) and Kandahar in Afghanistan where live tests on animals using agents such as cyanide, ricin, sarin, anthrax and botulinum were carried out. Al-Qaeda was responsible for plotting a number of WMD attacks including one that involved a Bahraini cell who intended to use a crude cyanide gas device known as the ‘mubtakkar’ (meaning ‘invention’ in Arabic) to attack the New York city subway.

More recently, ISIS too has actively pursued WMD. A number of chemical and biological weapons facilities were found by security forces in northern Iraq and Mosul where the group planned to disseminate biological and chemical agents using drones. A laptop seized from a Tunisian ISIS member in 2014 revealed a 19-page manual detailing the process of developing and weaponising the bubonic plague from infected animals. In October 2019, an ISIS cell in West Java, plotted a suicide attack using abrin toxin found in rosary pea seeds. It is estimated that 0.7 micrograms of abrin could kill 100 people.

The recent Covid-19 pandemic has also seen a rise in propaganda activities by terrorist groups. ISIS has reframed the virus as a divine retribution against the infidels: China for their mistreatment of the Uighurs and the West for the persecution of Muslims. Al-Qaeda has called the virus the ‘smallest soldier of God’ and urged people to convert to Islam. White-supremacist groups have blamed the Chinese and the Jews for creating the virus. Both the jihadists and white-supremacists have also called on their supporters to carry out attacks by infection i.e. by coughing or spreading bodily fluids onto others. The sheer socio-economic impact of the virus and the weaknesses and vulnerabilities in governmental responses to the pandemic may likely rekindle the interest and pursuit of WMD by these terrorist groups.

There are three stages in the production of bio-weapons; acquisition-cultivation, synthesis and weaponisation-delivery stage. Whilst the first stage is simple and inexpensive, it is the final stage that is usually the most challenging. This is because the weaponisation process which involves a delivery mechanism (usually aerosolisation) of the bio-agent is dependent on many external factors such as temperature and humidity. Therefore, carrying out a large-scale bio-attack is difficult but if successful, will lead to a mass casualty situation.

A good example is the 2001 anthrax attack in the US. Only around 1gm of anthrax spores was used in the attacks but it resulted in five deaths, 22 illnesses and 30,000 needing to be treated with preventive antibiotics. The direct economic cost incurred was more than US$1 billion. While anthrax has a higher fatality rate than coronavirus, it is much less contagious than the coronavirus. The coronavirus highlights the dangers of a virus that is airborne and one that does not require an external delivery mechanism. In this case, humans are the delivery mechanism.

The Covid-19 outbreak has thought us a number of valuable lessons. Firstly, nations must take the threat of pandemics and the possibility of biological or chemical attacks seriously. Each nation should have a comprehensive strategic action and crisis management plan in the event of an outbreak or attack. National health organisations like the WHO should play a more proactive role and remain bipartisan in dealing with these crises. Nations must be compelled to remain transparent in reporting and identification of pandemics. China’s early management of the crisis has been questionable in view of the allegations of downplaying the pandemic, suppressing whistle-blowers and manipulating statistics that have been raised against them. Healthcare systems should be beefed up, trained and adequately equipped to deal with outbreaks. There should also be increased inter-agency, inter-sectorial cooperation between the healthcare sector, security, military and civil defence in dealing with these threats. Governments, particularly high-risk nations should also invest in CBRN defence capabilities in order to safeguard themselves against future WMD threats.

To conclude, this pandemic should be a lesson to all nations to deal not only with future outbreaks but also face the evolving threat of biological and chemical terrorism in line with the rapidly developing technological landscape of the world.

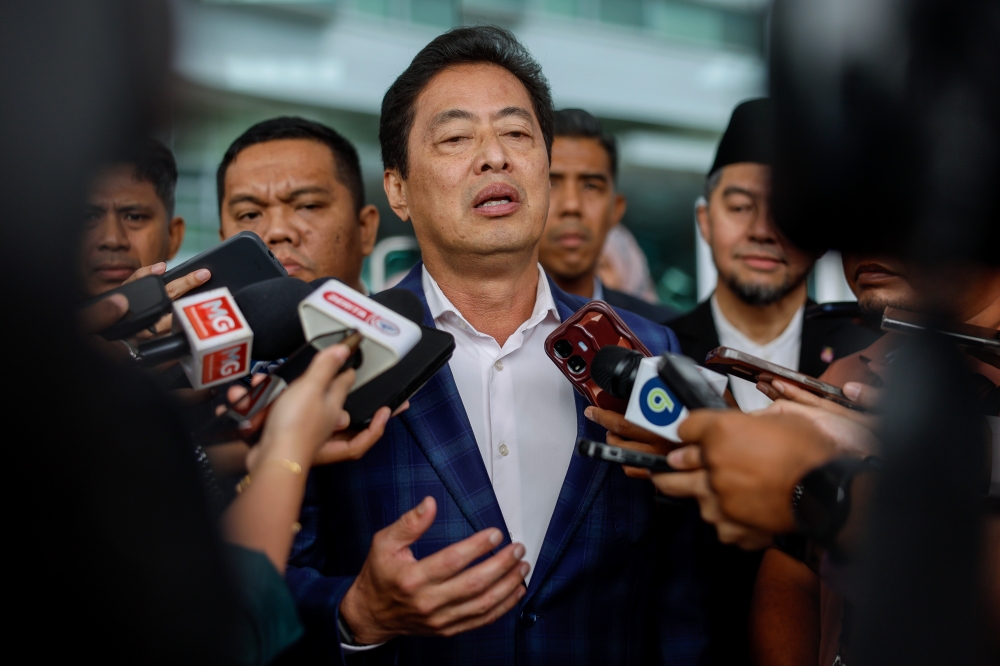

* Rueben Ananthan Santhana Dass is a graduate student in Defence and Strategic Studies at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

** This is the personal opinion of the writer or publication and does not necessarily represent the views of Malay Mail.