OCTOBER 12 — Nobody likes taxes.

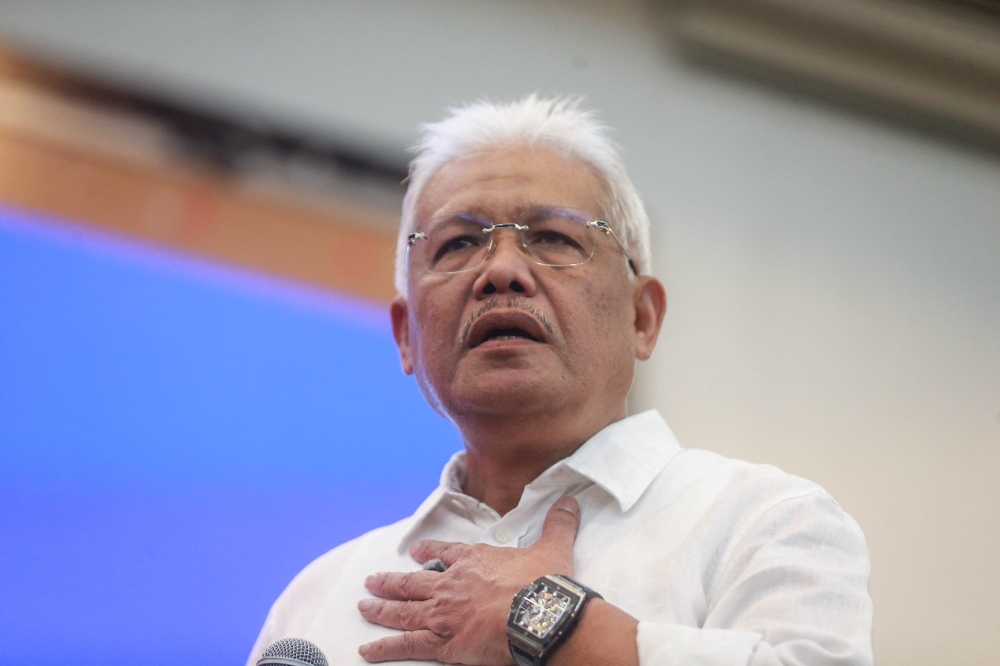

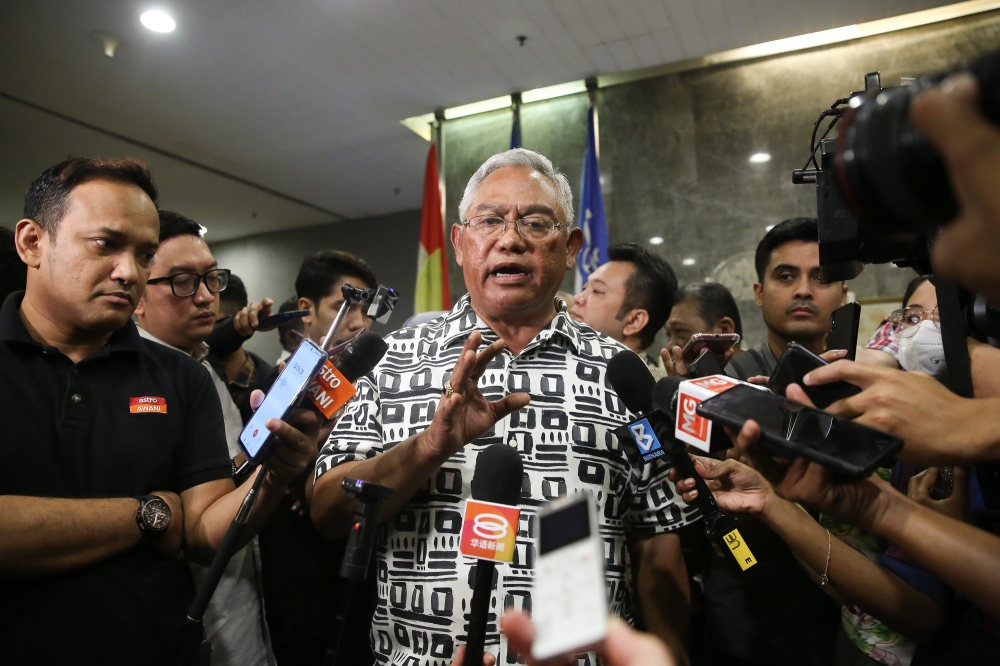

The prime minister warned us that the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government may impose new taxes to address the debt left by the Barisan Nasional (BN) administration.

Some economists cautioned the government that an inheritance tax or capital gains tax could affect the economy and hurt Malaysia’s image as an investment destination.

The government keeps saying that it is facing RM1 trillion debt, including government guarantees. Moody’s has said direct government debt was RM687 billion, as it maintained its estimate of direct government debt at 50.8 per cent of GDP in 2017.

The World Bank cut its economic growth forecast for Malaysia this year from 5.4 per cent to 4.9 per cent, warning that the expansion pace could steadily slow through 2020. It said a lower-than-expected government expenditure would hurt growth prospects of the economy that is facing “substantial” external risks. Economic growth was predicted to slow to 4.7 per cent in 2019 and 4.6 per cent in 2020.

Our ringgit remains weak at 4.15 to the dollar. In short, things are looking bad.

One of the main reasons the government has to scrape the bottom of the barrel for new sources of revenue is because it scrapped the goods and services tax (GST), losing RM21 billion in doing so.

The then deputy finance minister said in November 2017 that only 15 per cent of the 14.6 million labour force earned enough to pay personal income tax in 2016, or 2.27 million people.

Some additional 261,000 taxpayers fell outside the taxable category when the Najib administration reduced two percentage points in the personal income tax rate for three tax bands in the 2018 Budget, benefitting those with annual taxable incomes of between RM20,000 and RM70,000.

Since the reintroduced Sales and Services Tax (SST) collects far less tax than the GST, any new taxes will only burden the middle class that already carries the weight of financing the country on its shoulders.

The government claimed that SST would reduce the price of goods and services. But prices don’t seem to have gone down. If anything, food is more expensive now. A simple hawker meal including a drink costs about RM10. Grab has raised prices as well, charging RM7 to travel less than 5km.

Eating out at a nice-ish air-conditioned restaurant during the weekend costs at least RM50. Yet, our wages have stagnated, growing at a far slower pace than the cost of housing and education.

In the days of old before the GST was implemented in 2015, Malaysians were generally docile because most of them did not pay tax. Citizens did not feel the need to demand accountability from the government, since none of their hard-earned ringgit went to the State.

So, without any real (financial) stake in the country, Malaysians happily voted in the same government for 60 years, tolerating a lot of nonsense that happened throughout the decades (not just for the past 10 years that some former ministers would have you believe).

Everyone — the rich, poor and middle class — should share the burden in developing the country, no matter how big or small their contribution. A consumption tax would have allowed that — the poor who consume less get taxed less, while the rich who consume a lot more fork out more to the State.

Yes the old regime was corrupt and responsible for the mess that we’re in now. But that doesn’t make the proposal of new taxes any more palatable. The rich will get on fine; it is the middle class who will suffer.

There is a limit to how much “sacrifice” we must make for the country, especially when what is asked of us seems one-sided.

The government genuinely seems to be trying to do a good job so maybe they are just bad at communication. Making policy arbitrarily without consulting stakeholders and claiming misquotes by the media every few days or so doesn’t inspire confidence though.

It may seem unfair to resent the new government for the wrongs of the old, but the fact is that we are all only trying to get by day to day, hoping that we won’t suffer any sudden major mishaps or illnesses that will wipe out our savings and put us at risk any time.

PH cannot hope to convince us by repeating the tired RM1 trillion debt excuse without first proposing other methods of cutting spending, such as drastically trimming the 1.6 million bloated civil service.

Emoluments, or civil servants’ salaries, amounted to RM78.1 billion in Budget 2018.

Retrenching 13 per cent, or 208,000, of civil servants will save the government a whopping RM10 billion, plugging half the hole left by the abolition of GST.

The 200,000 civil servants only make up less than one per cent of the population.

So before the government suggests ridiculous things like new taxes that will hurt the two million middle class who pay income tax, it should first review unnecessary staff on its payroll.

It is the government who should make the first sacrifice, not the overtaxed middle class.

* This is the personal opinion of the columnist.