KUALA LUMPUR, Jan 9 — Now that Malaysia has declared that social media and internet messaging giants with at least eight million local users come under the country’s laws from January 1, can anything be done if these overseas-based companies break or ignore the rules?

What happens if these companies do not have a local office or even appoint a local representative in Malaysia to answer for any non-compliance? What options would Malaysia have?

Lawyers told Malay Mail that Malaysia could go overseas to get non-compliant platforms to pay penalties, with one lawyer also suggesting slowing down the speed of accessing such platforms.

Not sure what these platforms are? Think of apps like WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, Telegram, TikTok and YouTube.

Here’s what lawyers say

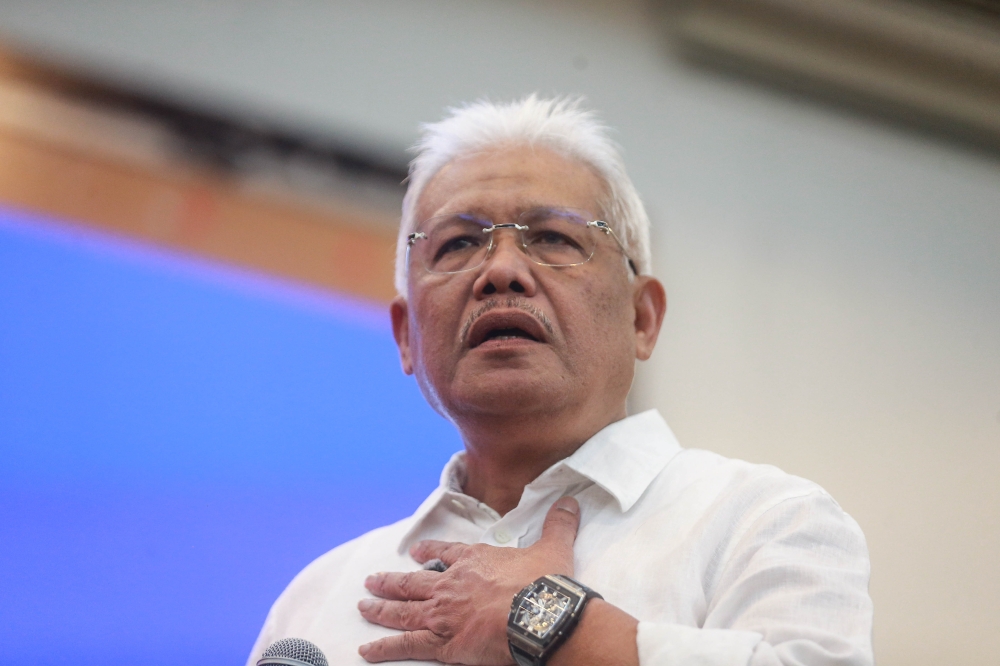

Foong Cheng Leong, co-deputy chair of the Bar Council’s Intellectual Property Committee, noted that the Malaysian government had since January 1, 2025 tried to compel these service providers to register themselves as licensees.

But since not all service providers had done so — with some even pushing back on the requirements — he said the government used its powers under the Communications and Multimedia Act’s (CMA) Section 46A to declare these companies as licensees from January 1, 2026.

Just like other licensees under CMA, these social media and internet messaging firms will now face legal consequences if they do not comply with local laws and licence conditions, he said.

“Foreign companies run a peril if they do not comply with law, rules and regulations,” he told Malay Mail.

For example, if companies do not comply with regulator Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission’s (MCMC) directions, they can be punished under CMA’s Section 53 with a maximum RM1 million fine or maximum 10 years’ jail or both, he said.

“Practically, it may be hard to enforce if they choose to ignore, especially if they will never step foot in our jurisdiction,” he said.

“Perhaps the government will have to be a bit more creative in dealing with foreign companies operating in Malaysia who ignore our laws. The traditional fine and imprisonment may not work,” he said.

Foong proposed some possible methods of enforcement against non-compliant foreign service providers, including slowing down or “throttling of the speed to access the platform”.

He said that the Malaysian government could carry out civil action by going to courts overseas to enforce damages outside of Malaysia.

“Yes, in fact, Section 39(3) of ONSA has this provision. A civil debt may be recoverable in other countries by filing it in court,” he said.

He was referring to the Online Safety Act 2025 (ONSA), which also applies to these platforms from this January onwards as they are now CMA licensees.

Section 39 states that MCMC may impose a maximum RM10 million financial penalty on such companies which fail to comply with their duties under ONSA, with Section 39(3) stating that this financial penalty “may be recoverable as a civil debt” that has to be paid to MCMC.

Foong suggested the government could also freeze assets, including intangible assets in Malaysia such as intellectual property rights in the form of trademarks and patents.

No ‘buts’, being licensed in Malaysia means platforms must obey local laws

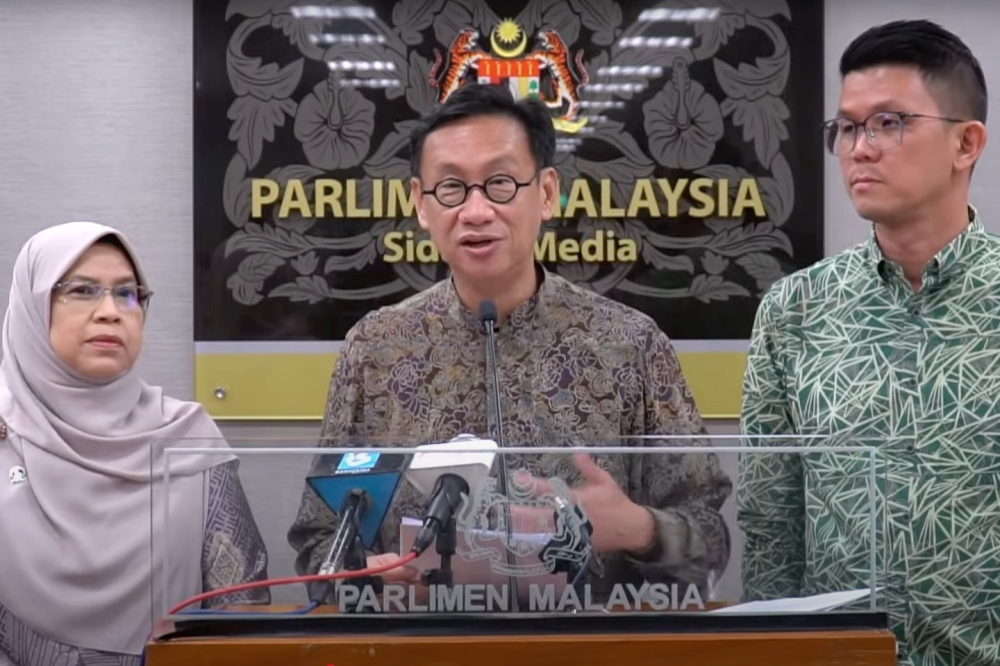

Sathish Mavath Ramachandran, co-chair of the Bar Council’s Legal Tech, AI and Sandbox Committee, said the automatic registration was fair as it only affects several major platforms.

He said the automatic registration is a “positive development and most welcome, timely, topical”, as it would help fight online harms such as scams, illegal betting and gambling.

“This is part and parcel of a broad policy objective — to tackle cyber crimes such as online fraud, cyberbullying and child sexual offences, and to enhance accountability of platforms operating in Malaysia,” he told Malay Mail.

He said MCMC will regulate these foreign companies as they are now licensees, which means they must now comply with MCMC’s licence conditions, standards and directions.

“It is the law. They must comply. Or MCMC will enforce it under the CMA. And ONSA applies to them also. And all other Malaysian laws,” he said.

He said these licensed platforms — which make money from Malaysians such as through advertisements — are effectively being told that they have to follow the law just like any other CMA licensees: “If you want to do business in Malaysia, you have to comply with Malaysian law.”

Being licensed = Possible for money laundering probes on suspicious transactions

By turning these platforms into licensees, it would mean there are more options to enforce local laws on them — including laws on cyber crimes, he said.

He gave the hypothetical example of MCMC investigating complaints about group chats on apps being used to fund terrorism or facilitate terrorism financing or discussing how to build weapons, and what would happen if a platform refuses to do anything about this.

In such a scenario, he said Malaysia’s anti-money laundering and anti-terrorism financing regulator Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) could step in to investigate, regardless of whether the platform is a foreign or local company.

For platforms which get income from paid subscriptions to its services such as group chats, he said BNM could restrict these platforms from receiving fees from Malaysians, if there is non-compliance.

He said companies can also be required to pay a digital tax or service tax as they would be considered to be doing business in Malaysia.

Options to ensure platforms follow the law

Sathish said MCMC could impose civil penalties or pursue prosecution for criminal liability, adding that Malaysia can also go abroad to enforce court orders on platforms that refuse to comply.

Previously without ONSA, MCMC had to resort to going to court to get an injunction order against Telegram and two Telegram channels “Edisi Siasat” and “Edisi Khas”, to stop the two channels from publishing and circulating 33 allegedly defamatory and harmful articles.

But with ONSA in place since this January, MCMC has the power to order platforms to remove harmful content or to block accounts with harmful content, he said.

He said MCMC also has the option to publicly “name and shame” offenders who put up harmful content on these platforms.

Unlikely for Malaysia to ban or block apps for non-compliance

What if these platforms choose not to comply with their obligations under Malaysian laws, such as breaching their licence conditions by not appointing a local representative?

“If they do not comply, it jeopardises the license,” he said.

If the license for any of these platforms is revoked and they become unregistered, they “cannot operate in Malaysia” and would effectively be blocked in Malaysia, he said.

Calling this the “ultimate sanction”, Sathish however said the government would not ban or restrict access to non-compliant platforms: “That won’t happen.”

He said Malaysians would be able to continue using these platforms, pointing out that MCMC now has the full range of powers under Malaysian laws to take action against all these platform providers.

Sathish also pointed out a ban would not happen as CMA, the Bill of Guarantees by both MSC Malaysia and its successor Malaysia Digital had said there would be “no censorship of Internet”.

CMA’s Section 3(3) states that nothing in this law shall be interpreted as “permitting the censorship of the Internet”, while the latest Bill of Guarantees guarantees that the Malaysian government would “ensure no censorship of the Internet”.

In a recent interview, MCMC told Malay Mail that the regulator’s focus is not to ban platforms, but to instead work with them to ensure Malaysians’ online safety by fighting the “common enemy” such as paedophiles and scammers.

Recommended reading: