KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 13 — It is no secret that there is a need for Malaysia to broaden its revenue base in lieu of a value-added tax (VAT) or the goods and services tax (GST), with the majority of Putrajaya's revenue coming from direct taxes such as income or corporate taxes, and dividend from Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas).

Malay Mail's report last month showed that Malaysia is not only relying more on personal income tax compared to its neighbours, but income tax in total contributed just 11.8 per cent compared to the gross domestic product (GDP) — below the Asia-Pacific average of 19.8 per cent, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of 34.1 per cent.

“According to the World Bank, tax revenues above 15 per cent of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) are a key ingredient for economic growth and, ultimately, poverty reduction. As a percentage of GDP, total tax revenue indicates the share of a country's output that is collected by the government through taxes,” Fung Mei Lin, tax partner and entrepreneurial and private business leader with accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers Malaysia told Malay Mail.

“From Malaysia’s statistics, it means that for every RM1 of GDP generated by Malaysia, the government only collects 12 cents. Therefore, there is an urgent need for Malaysia to widen its tax base through introduction of new taxes, and at the same time, to plug the tax leakages to increase the tax revenue,” she added.

With Budget 2024 set to be tabled this afternoon, all eyes will be on Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim on how his administration will increase revenue for the nation's coffers.

Malay Mail takes a look at several taxes that may finally come into effect next year:

Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

In what could be the clearest sign yet, Anwar who is also finance minister said while tabling the Half-Term Review of the 12th Malaysia Plan in Dewan Rakyat that the CGT will be implemented in 2024.

Anwar had previously announced the plan to tax unlisted shares under Budget 2023, a move that came after years of public pressure to raise taxes on the rich amid growing anger about wealth inequality.

Economy Minister Rafizi Ramli also announced the implementation last month, listing it as one way to fiscal sustainability.

In a keynote address delivered at the Invest Malaysia conference in March this year, Anwar said the plan to tax capital gains on unlisted shares would happen only after “extensive engagement” with all parties, a seeming attempt to allay shareowners’ concerns.

He also insisted then that the tax would not affect listed shares or the disposal of unlisted shares for an approved initial public offering.

The introduction of the CGT aims to align Malaysia with international taxation norms, joining nations such as Thailand (20 per cent), Indonesia (22 per cent), Vietnam (20 per cent), Cambodia (20 per cent), and Myanmar (10 per cent for non-oil and gas, and 40 to 50 per cent for oil and gas sector), which have already implemented similar measures to tax capital gains.

In Asia, only Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong do not tax capital gains. All other significant economies subject capital gains to normal income tax rates or have a special rate for capital gains.

At present, Malaysia only imposes a Real Property Gains Tax on gains arising from the sale of real property at a rate of 30 per cent.

Luxury Goods Tax

In February when the CGT on unlisted shares was announced, Putrajaya also announced its intention for a Luxury Goods Tax (LGT) on high-end items, usually including luxury automobiles, high-end personal goods like watches and jewellery, and even extravagant assets like yachts and private jets.

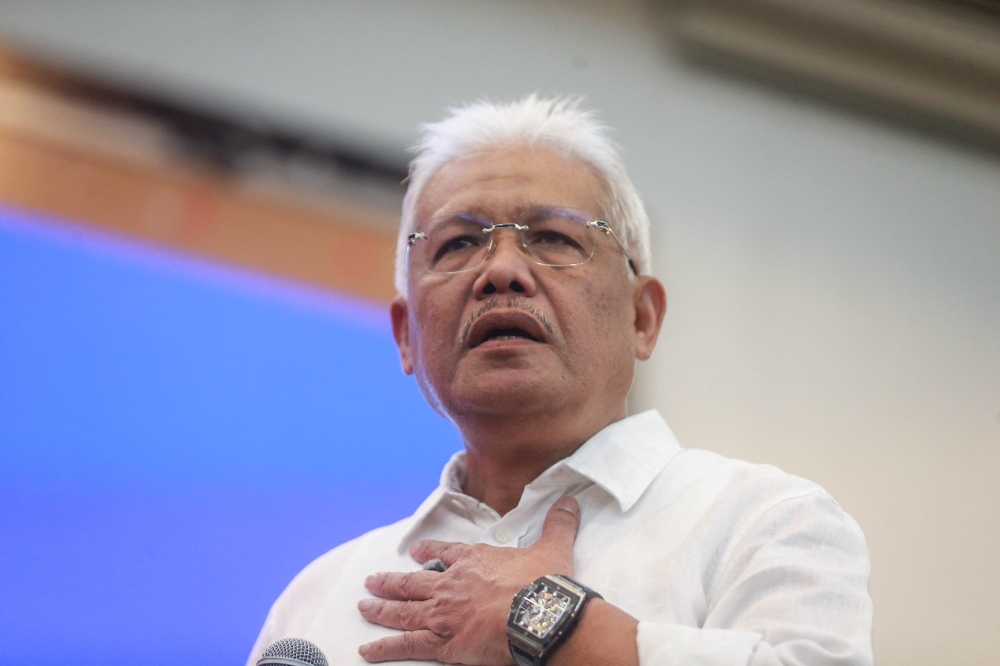

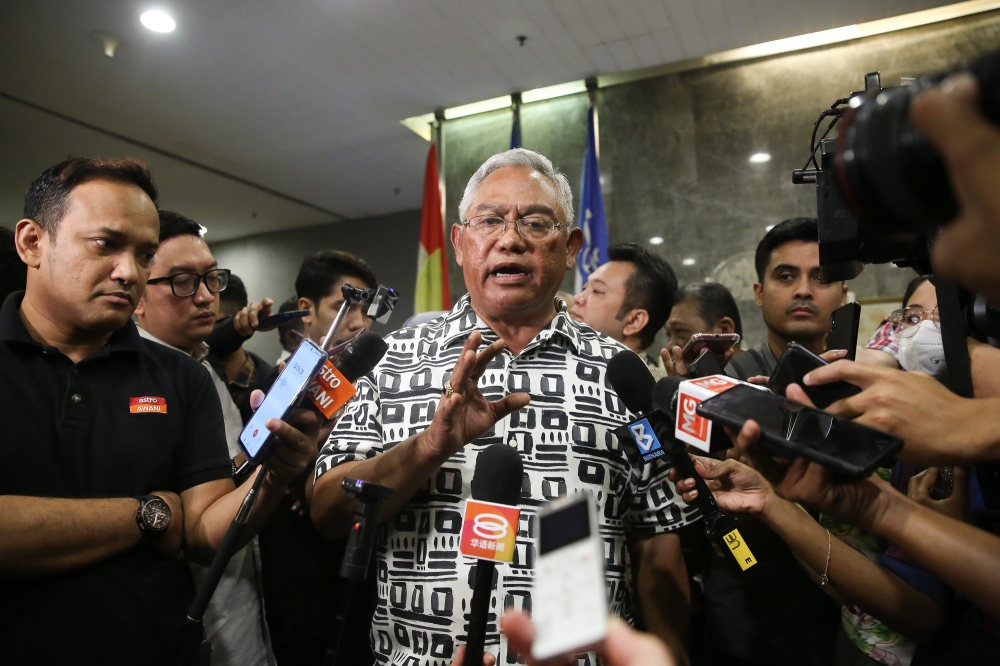

This proposal was met with scepticism from former prime minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob, who warned that the LGT can potentially discourage foreign tourists who prefer to shop from coming to the country.

The Chartered Tax Institute of Malaysia (CTIM) last week said it believes the government “is studying the best practices in other countries and how it can be best implemented in Malaysia with an expected rate from three to five per cent”.

Online Sales Tax

One notable measure that received mixed responses was the 10 per cent online sales tax on online purchases of low-value goods (LVG) below RM500. Although this move was met with public backlash, some lawmakers have proposed an alternative—imposing a 15 per cent global tax on multinational enterprises (MNE) as a substitute for the LVG tax.

Former finance minister Lim Guan Eng said the additional revenue for online LVG foreign purchases and unspecified hundreds of millions of ringgit more collected from online LVG domestic purchases will be borne by low-income groups.

Lim added that according to the OECD, a tax rate of 15 per cent on MNEs would reallocate profits of more than USS$125 billion (RM556.62 billion) from about 100 of the world's largest and most profitable MNEs to all countries.

Tax services firm Deloitte also said earlier this year such a tax “would shift the onus of charging and collecting sales tax from the Customs to the seller of LVG” — including both who sell LVG on an online marketplace and the marketplace operators themselves.

As of March this year, the Royal Malaysian Customs Department said this tax on LVG has been postponed.

Other taxes

Similarly, in March, Customs announced the postponement of two other taxes: service tax on goods delivery services and the expansion of excise duty to pre-mixed products with sugar content over 33.3 grammes/100 grammes.

In Budget 2022, the government announced the excise duty for pre-mixed products to curb the rise of diabetes and obesity.

The service tax on deliveries aims to provide equal treatment among delivery providers while the tax on LVG aims to provide equal treatment to local and imported goods.

Return of Goods and Services Tax (GST)?

In February this year, World Bank’s lead economist Apurja Sanghi said Malaysia needs to raise its revenue base and the best way to do so is by implementing the GST — pointing to how it is not by coincidence that 174 countries employ the consumption tax to fill their coffers.

However, it is very unlikely that the Anwar administration will rush into re-introducing the divisive consumption tax that was abolished by the previous Pakatan Harapan government in June 2018, after three years of implementation.

Earlier this year, Anwar insisted that his government will introduce neither GST nor broad-based consumption tax, but will instead tighten subsidies for the rich.

One of his deputy finance ministers, Steven Sim Chee Keong also said that it is not the right time yet to implement GST despite acknowledging its advantages.

Sim said the government’s view is that the country is still in the recovery phase post-pandemic and is facing various global economic challenges due to geopolitical unrest, and therefore is still not ready to implement the GST.