KUALA LUMPUR, July 18 — The new government has adopted a more diplomatic stance towards China’s continued claim over Malaysian territorial waters as it was now more dependent on the superpower for trade after Covid-19 wreaked havoc on the world economy, said analysts.

They told the South China Morning Post that the seemingly new approach — evidenced in Foreign Minister Datuk Seri Hishammuddin Hussein’s recent remarks on the matter — was also necessitated by the close trading ties between both countries.

They pointed out that Brunei — one of four countries disputing China’s claim in the South China Sea — was similarly diplomatic as the sultanate has a joint petrochemical venture with China and grew noticeably quieter on the issue after global oil prices plunged.

“The (Malaysian) government is completely downplaying any Chinese assertiveness. They need the investment, trade, and now Covid-19 assistance,” Zachary Abuza, a Southeast Asian security expert at the Washington-based National War College, was quoted as saying.

However, he argued that this was not a fundamental shift in Malaysia despite the appearance, noting that the Defence White Paper prepared during the previous administration also did not flag China as a major security concern.

On July 15, Hishammuddin responded to a National Audit Department’s report that Chinese ships encroached into Malaysian waters 89 times between 2016 and 2019 by saying this was no longer an issue.

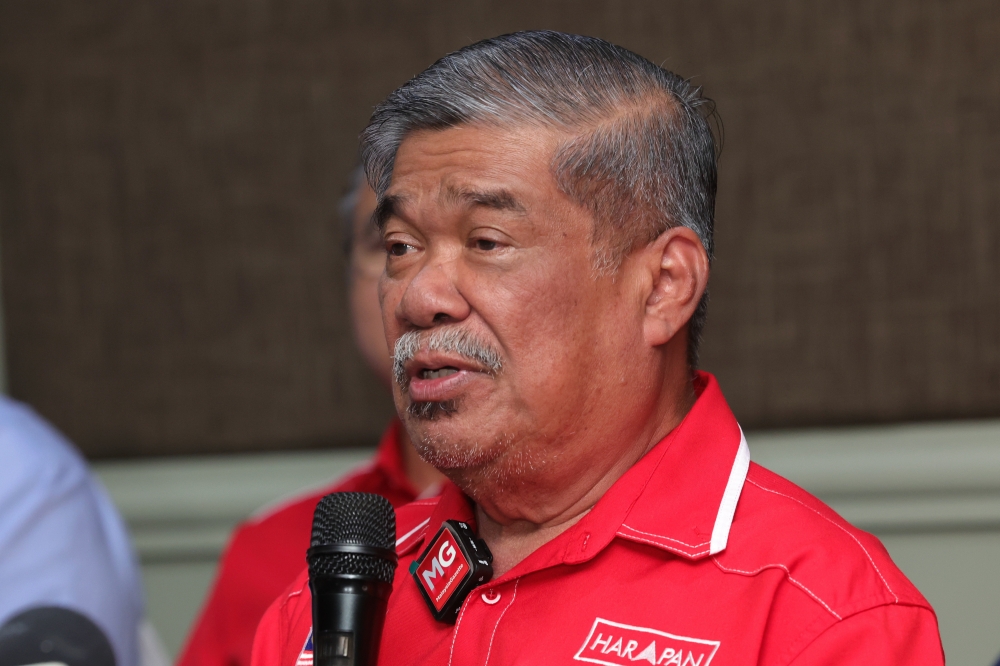

This led to a scathing response from former foreign minister Datuk Seri Anifah Aman who said Hishammuddin was either “in denial or ignorant” about the encroachment.

Anifah kept up his criticism notwithstanding a subsequent clarification from Hishammuddin.

According to Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) senior analyst Shahriman Lockman, Malaysia’s tact was not recognition of China’s claim on its territory and he noted that it has consistently contested such claims, including through a note verbale to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

“Malaysia is rhetorically quiet, but it does stubbornly persist in its oil and gas activities and its lawfare in the South China Sea,” he was quoted as saying in the SCMP report.

“China is crucial to Malaysia’s economic future and will probably continue to grow as a military power. So the policy needs to be tempered by the reality of China. Policy therefore becomes a series of anguished calculations and adjustments.”

Shahriman also suggested that Vietnam, yet another contesting country, was confrontational towards China in the issue because the two countries have had bloody conflicts in the past.

Malaysia and three other neighbours are locked in a regional maritime dispute with China stemming from the so-called “nine-dash-line” demarcation that the latter has used to unilaterally claim significant swathes of the South China Sea far beyond what is territory.

The matter escalated after China became more aggressive in its incursions into the contested waters, which analysts previously concluded was a policy intended to play up nationalism at a time when Chinese nationals were growing disillusioned with the ruling party due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

China has also sent naval vessels to the area when other claimants had only deployed civilian craft, prompting rival superpower the US to depoly a carrier fleet to the area for military exercises seen as a warning to China.

On Monday, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared his country’s formal opposition to the majority of China’s claims on the South China Sea and said Washington would not allow Beijing to use the region as “its maritime empire.”

Despite the patent support of their interests against China in the matter, Vietnam was the only one of the four countries to openly embrace Pompeo’s statement.