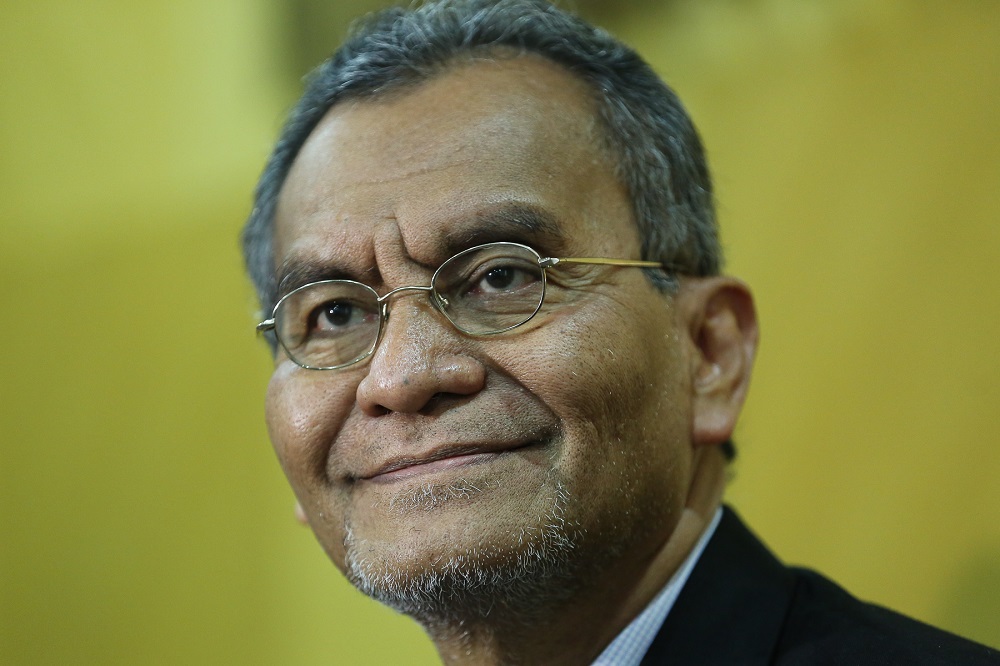

KUALA LUMPUR, June 27 — Health Minister Datuk Seri Dzulkefly Ahmad said today the government must handle its plan to decriminalise drug dependency “with care and tact”.

In the first official statement since his ministry made a joint announcement with the Home Ministry on the proposal to decriminalise substance dependency on Tuesday, Dzulkefly said the push for drug law reform is timely.

However, he was quick to point out that decriminalisation should not be mistaken for drug legalisation.

“Malaysia is about to embark on a significant game-changer policy of Decriminalisation Drug Addicts & Addiction,” the minister said.

“This is not to be mistaken for legalising drug and l again categorically emphasise that decriminalising does not mean that we are legalising drugs.”

The remark signalled what some in the administration said was Pakatan Harapan’s (PH) anticipation that the issue could become the next moral battleground, as political rivals would likely play up the issue in light of conservatives’ insecurity about drug users.

Sources familiar with the administration’s decriminalisation plan told Malay Mail that some within the ruling coalition believe the issue could give opponents fresh political fodder, with the Opposition likely use this to reinforce its claims about PH’s supposedly “more liberal” tendencies.

Malaysian society is generally conservative and deeply averse to drug abuse, a perception formed from a decades-long campaign that demonised the latter as criminals.

Past attempts to adopt harm reduction treatment for addiction often met resistance, especially from Islamist party PAS that believe a lenient approach would only encourage more to abuse drugs.

“Our political nemesis would go to town with this... it is a very delicate subject to handle,” a source said.

But experts said data-solid evidence show harm reduction have been more successful in treating addiction than harsh punitive laws.

Data from the Health Ministry’s programmes have shown harm reduction’s accomplishment in curbing relapse among heroin addicts, and at the time drastically reduce HIV transmission via intravenous drug use in the country.

From 2005 to 2016, the cases of injection drug use-transmitted HIV dropped from over 3,000 cases to just slightly above 100.

Dzulkefly reiterated this point in his statement today, saying decades of evidence has clearly demonstrated that decriminalisation is a sensible path forward.

“It would reap vast human and fiscal benefits, while protecting families and communities,” he said.

More than 30 countries have decriminalised addiction, often with notable success. Research has shown that decriminalisation decreases drug use, saves more tax money and help former addicts accomplish more socially.

Decriminalisation is the removal of criminal penalties for possessing and using a small quantity of drugs for personal use, as opposed to those who are involved in trafficking of drugs.

Trafficking of drugs will remain a crime, the minister said.

Pointing to the marginal fluctuations in the number of drug-related arrests over the years, experts said the punitive approach has failed to treat addiction, a highly complex chronic relapsing medical condition.

They argue that public rehabilitations lack the means and expertise, while criminalisation often ignore root causes of addiction like poverty, mental health problems or peer pressure.

“If someone continues to take drugs, biological changes start happening in their brain,” Dr Dzulkefly said.

“Therefore, it is not so easy to reverse that biological change.”